By Natasha Phillips

28 Dec – The last 12 months have been challenging ones for Iran. Struggling with economic mismanagement, sanctions and nationwide demonstrations, Iranians have experienced deepening poverty, environmental disasters and increasingly violent crackdowns by government forces during demonstrations.

Nevertheless, Iranians were unfazed by mass detentions and rumors of physical torture during police investigations, continuing their strikes and social media campaigns throughout the year. Iranian officials have also been resolute. Efforts at stemming the effects of US sanctions through the building of economic relationships with countries like China and Russia were consistent, though their impact on Iran and the rest of the world remains unclear for now.

• Protests which began in Iran in December 2017 swept across into 2018, and for the first time international media began to report on the demonstrations. Concerned by a rising number of protestors across the country who seemed to be angered by corruption and inequality, the Iranian government responded by sending Revolutionary Guards to put an end to what IRGC commander Major General Mohammad Ali Jafari called “the new sedition.” Prominent individuals began to lend their support to protestors, including Nobel Prize Winner Shirin Ebadi as well as high profile Iranian actors, directors and producers around the world. Physical demonstrations by Iranians living in countries like Germany and Britain followed. While Khamenei took the view that other countries had a hand in the protests, the Supreme Leader also seemed to acknowledge that the unrest was driven at least in part by failed domestic policies.

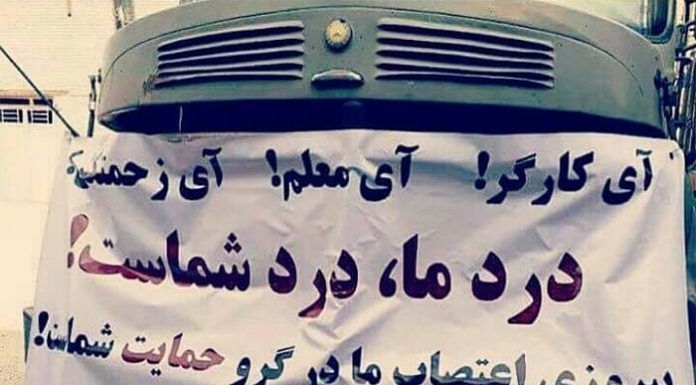

• The arrest, detention and suspicious deaths of protestors inside Iran’s jails became a worrying feature of the demonstrations in 2018, but a feature that did not deter protestors. In February, more strikes took place as unions, teachers, students and doctors took to the streets to highlight Iran’s economic crisis. The government responded with violent clampdowns on protestors. Demonstrations over Iran’s severe drought and Iranian women being banned from football stadiums followed. Surprise mass protests organized by Iran’s influential bazaar traders in June led to a call by Khamenei to punish anyone “disrupting economic security.” Iranians wrote letters to politicians, started online petitions and social media campaigns as protests and strikes raged on. Truckers staged protests nationwide and vowed to support other demonstrators despite being arrested in their hundreds as they protested peacefully around the country. Steelworkers, farmers and workers at a sugar cane mill in Ahvaz joined the protests. Emboldened by what appeared to be a unified civilian front, parents and their children lent their voices to the protests in November. As of December, the protests show no sign of slowing.

→ Link to sources

• In 2018, the Iranian government also focused its attention on children, religious minorities including Bahai’s, Sufis, Zoroastrians and Dervishes, human rights activists, journalists and environmentalists. Officials arrested people on often unspecified charges, or for spying. Students as young as 16 were arrested in January for protesting against youth unemployment. Women removing their veils in public in Iran in protests against laws that make the wearing of the hijab compulsory were arrested and on occasion seriously injured by police. Human rights groups criticized Iran’s female politicians for their slow and sometimes piecemeal responses to the arrests. In February, Kavus Seyyed-Emami, one of eight members of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation arrested on charges of espionage, was said to have committed suicide in jail. The remaining seven environmentalists had their charges extended. Dual nationals were arrested throughout the year on spying charges, sparking concerns over their detention including the arrest of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, whose case has been highlighted by several British politicians including Prime Minister Theresa May. The arrest and forced confession of a teenager who shared a clip of herself dancing on YouTube made international headlines, leading to a viral campaign on Twitter in which thousands of teenagers and adults shared videos of themselves dancing in solidarity with 17-year-old Maedeh Hojabri.

• In a bid to quell civil unrest over corruption, Iran’s government began to arrest, and sentence to death, businessmen and traders accused of manipulating Iran’s currency and stealing. Vocal opponents of the Iranian government were also targeted. Officials rounded up campaigners including nine Iranian women’s rights activists, summoned to Evin Prison in November by the prison’s prosecutor’s office. In December, reports confirmed that social media activist Vahid Sayyadi Nasiri had died in prison following a hunger strike. On 21 December, the Center for Human Rights in Iran reported that law student Amir Chamani was given a six month prison term for social media posts criticizing the government.

• Civil liberties and child rights campaigners appeared to be groups of particular interest to Iranian officials towards the end of the year as the government stepped up its arrests of human rights activists inside the country. Laily Khatami, a child and women’s rights activist from Kermanshah was arrested and charged with spying. Fariborz Shahraki, a lawyer who had followed up Laily’s detention with officials was also later arrested. Reports by an Iranian journalist that he had been tortured during his interrogation went viral on Twitter along with details of Laily’s arrest. According to Human Rights Watch, these arrests signaled an escalated crackdown on legal professionals and human rights activists in Iran. Among those activists still detained are high-profile civil liberties lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh and her husband Reza Khandan, and Narges Mohammadi. Hadi Ghaemi, Executive Director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) asked the international community to stay focused on unlawful detentions in Iran as the new year approaches.

→ Link to sources

• The Iranian government remained determined to exercise influence on the global stage with the onset of U.S sanctions, after Trump pulled America out of the nuclear deal in May. Diplomats and analysts saw the move as a strategy to force regime change in Iran, a claim the U.S government strongly denied throughout the year, calling the policy an attempt at changing the regime’s behavior instead. Europe scrambled to keep the deal alive, trying first to renegotiate its terms and then looking into special purpose vehicles (SPV) to ease trade between Iran and pro-deal countries. While some EU member states expressed doubt over whether reworked terms could salvage the deal, no state came forward to offer to host the SPV to facilitate business between Europe and Iran. Seeking out other options, Iran’s top officials took Trump’s sanctions to court in July, asserting that the penalties were illegal and in breach of a 1955 treaty between the two countries. Judges at the International Court of Justice, or World Court, told America to ensure that its sanctions did not restrict humanitarian aid to Iran. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo responded by telling the court that the sanctions would not affect aid to the country. Iran’s very public display of its military exercises and the launch of its first ever conference on defense threats, was followed by the US calling for a “liberal world order” in which countries like Iran would be cut out of international financial agreements altogether.

→ Link to sources