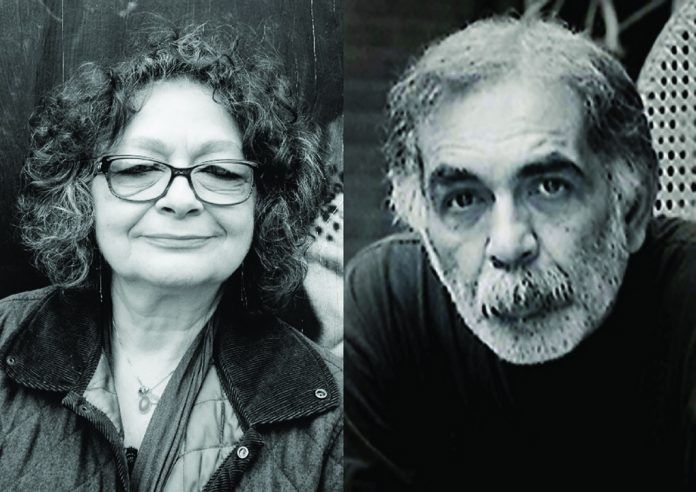

Hengameh Golestan was 18 when she met the man who would go on to become her husband – and one of the finest photo-journalists of the late 20th century. His name was Kaveh Golestan. He was 19.

Today, Kaveh is no more. On assignment as a BBC cameraman in northern Iraq in April 2003, he met his untimely death on a minefield at the age of 52. Yet his legacy lives on: through the tireless efforts of Hengameh, his photographer wife.

Kaveh and Hengameh were recently exhibited by the Shirin Gallery in Tehran. Rarely seen photographs by Kaveh were displayed in July, while Hengameh was part of a just-ended group show of Iranian female photographers.

Hengameh is a sprightly woman with frizzy, shoulder-length grey hair and a raspy chain-smoker’s voice. We meet at her previous photography exhibition, held at the Showroom gallery off London’s Edgware Road – where visitors can also sit at a communal table to peruse books and press clippings. The place is as unassuming as Hengameh herself. She makes it all the more informal by exhibiting her black-and-white photographs unframed.

The photos tell a powerful story: that of the legions of Iranian women who, in the early months of 1979, demonstrated against new laws including the obligation to veil in public. In one animated image, a group of women in Western-style winter coats march in a neat line, some waving their fists. The picture is historic: This was the last day that Iranian women appeared in public unveiled.

Hengameh caught the photography bug from Kaveh (son of the award-winning filmmaker Ebrahim Golestan).

Hengameh caught the photography bug from Kaveh (son of the award-winning filmmaker Ebrahim Golestan).

“When we met, he started showing me photographs that he took of ordinary people in the street,” Hengameh recalls. “I’d pin the pictures up on my wall. I was very much influenced by him.”

When she moved to England to study photography, Kaveh joined her. But he couldn’t see the point. “‘Why are you going to photography school?’ he would say. “I’ll teach you everything myself.'” And so he did.

Back in Tehran, Hengameh became Kaveh’s assistant, changing his cameras, doing his darkroom work, and shadowing him on assignments for the Ayandegan newspaper. She soon started feeling rather unwanted. “Whenever we went into a factory, the workers would start smiling at me. Kaveh would say, ‘My pictures are ruined. They’re all smiling at you. You can’t stay here!’ So I’d have to wait outside.”

Before she knew it, Hengameh was being invited over for tea by the workers’ wives. Hearing their powerful stories, she decided to turn them into her own photographic subjects. “I thought to myself, ‘Fate has led me to photograph this side of the story. Since Kaveh can’t come into the women’s homes, I’ll take pictures of them myself.’”

Over time, Hengameh accumulated a rich archive of photographs of these women which she is now looking to publish as a book.

Iran’s working classes – who were absent from official media representations of the country – were also Kaveh’s favourite subjects. They included the prostitutes living in Tehran’s so-called Citadel district. Kaveh portrayed them with empathy and respect. Rather than refer to them disparagingly as fahesheh (whore) or zan-e-kharab (fallen woman), he described them using the more dignified term zan-e-ruspi.

(Kaveh’s poignant photographs of the women have been widely exhibited across Europe in a string of recent exhibitions curated by Vali Mahlouji.)

Kaveh also depicted the construction workers who had left the countryside in droves to help build the homes of Tehran’s super-wealthy. Cut off from their next of kin, they were impoverished, and in some cases, desperately ill because of the toxic working conditions. They were the main clients of the women in the Citadel, explained Hengameh: “The upper-class men from uptown Tehran preferred to meet women in hotels.”

Within a few years, the revolution broke out. Kaveh Golestan became an overnight star, working for major news organizations including the Associated Press and Time Magazine. “Every day, there would be demonstrations in three different places, or a building under siege,” recalls Hengameh. With Kaveh busy taking news photos, Hengameh would head off to photograph everyday life: ordinary women and children, individual soldiers, commuters standing at graffiti-covered bus stops. “I wasn’t very brave,” she recalls. “Whenever I saw trouble, I’d hide in a corner and wait for things to calm down.”

At the end of every day, once Kaveh had wired his news photos for immediate publication, the couple would then set the remaining pictures to one side. “We would tell each other that one day, when we were too old to run around taking pictures, we’d sit home and publish books,” she recalled. “Sadly, that never happened. Kaveh left, and I stayed. So I am carrying on with the project.”

In 1983 – three years after the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq war – Hengameh gave birth to her son Mehrak (now a London-based rap artist). Fearing for his safety, she left Iran for Britain, where she has lived ever since. Kaveh traveled back and forth. He co-founded a London-based agency called Reflex. He took harrowing pictures of the Iran-Iraq war, becoming the first person to photograph victims of Iraq’s murderous poison-gas attack on the Kurdish town of Halabja. Today, his images are among the best-known visual documents of post-revolutionary Iran.

In the early 1990s, he switched to the moving image, the medium of the future. It was a perilous career move. His 1991 Channel 4 documentary “Recording the Truth” led him to be placed under house arrest in Tehran for two years (though his wife and son were allowed in and out of the country). He took the opportunity to teach photography students at his home, later becoming Tehran University’s first photojournalism instructor.

However a far greater peril awaited him on April 2, 2003. Arriving at Kifri in northern Iraq at around 3 p.m., Kaveh and his three BBC colleagues chose a citadel to the southwest of the town as a spot for live TV broadcasts. It was there that Kaveh stepped on landmines. He was the only one of the four to perish.

“It was the worst thing that could ever have happened to me,” says Hengameh.

Her aim now is to digitize the thousands of slides, negatives, and film reels that her late husband took before time destroys them all. It is a huge and expensive task, but a necessary one.

“Now that he is gone, the best thing I can do is prevent his work from disappearing,” she concludes. “That, and our son, have kept me going.”