Lady Homayoun Renwick, who passed away on July 5th in London, was the doyenne of Iranian philanthropy in the United Kingdom and a tireless promoter of Iran’s rich culture for more than 30 years.

Born into a military family in Tehran on July 11th, 1939, she was the daughter of Major Mahmoud Yazdanparast Pakzad. While still in her teens, she married Yussef (Joe) Mazandi. He was the founder and publisher of Iran Tribune, and a foreign correspondent for numerous media organizations, including United Press International, Newsweek, CBS, NBC and The Daily Telegraph. He introduced his charming spouse to the world. Though they parted ways in 1972, and she moved to Britain and remarried, they remained lifelong friends.

Within months of her arrival in London, she appeared in leading magazines, and gossip columnists toasted her hospitality skills. In 1979 she married Harry Andrew Renwick, 2nd Baron Renwick, and took his name.

Her first notable philanthropic activity was as the London Chair of the London Committee for the Special Olympics, a global organization that serves athletes with intellectual disabilities.

She then turned her attention to her lifelong passion: her native Iran.

Together with a group of well-intentioned Iranians living in London, Lady Renwick established the Friends of Persian Art and Culture at Cambridge University (Friends of Persian at Cambridge) in 1992, to ensure the continuation of Persian studies at the university. Their first fundraising dinner, held at the Banqueting Hall in Whitehall, became a template for subsequent Norouz galas for the promotion of Persian culture in the UK and elsewhere.

Professor Charles Melville of Pembroke College, Cambridge remembered her as the driving spirit behind his efforts to ensure the continuation of Persian Studies at Cambridge University. He emphasized that FPC’s work also enabled scholarship to thrive across Europe.

Professor Charles Melville of Pembroke College, Cambridge remembered her as the driving spirit behind his efforts to ensure the continuation of Persian Studies at Cambridge University. He emphasized that FPC’s work also enabled scholarship to thrive across Europe.

One of many events supported by the Friends of Persian at Cambridge was the Third European Conference of Iranian Studies, held in Cambridge in 1995, which attracted over 200 scholars and 130 papers from all over Europe, Iran, Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

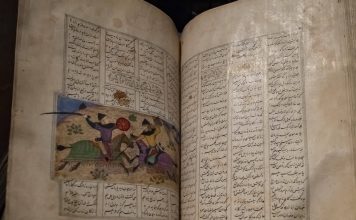

In 1996, Professor Melville dedicated the fourth volume of “Safavid Persia: The History and Politics of an Islamic Society,” part of the Pembroke Persian Papers, to her: “For Homayoun Renwick in admiration and gratitude,” he wrote.

Lady Renwick was also one of the first trustees of The Iran Heritage Foundation in 1992. The foundation, which celebrates the preservation and promotion of Persian culture, paid tribute to her as a generous community leader with a great sense of humour, “who initiated the celebration of the Norouz tradition in the UK. “

Homayoun Jan, as she was endearingly called by her friends and admirers, had a generous spirit and a passionate heart. She celebrated life’s beauty and sensuousness through her frequent recitations of Hafez, Khayyam and Rumi poetry. After her mother, Mrs Yazdanparast Pakzad, passed away, Homayoun Jan organized a night of poetry and music at the Nimatullahi Sufi Order center in London, in an effort to celebrate rather than mourn her life.

Lady Renwick dazzled the highest echelons of British society. Yet she also had a unique ability to engage people from all walks of life, of all ages and of all persuasions.

Reza Sepahi was a young student when he met Lady Renwick. He remembered her as the “keystone of the Turquoise dome that is the Iranian community in the UK,” According to Sepahi, Lady Renwick helped build bridges between a generation to whom Iran was everything and the younger generations that did not know Iran “by making being Iranian cool and fun.”

She was appointed as the UK Ambassador of the US-based Nowruz Commission in 2012.

In 2015, she gathered Ambassadors to the Court of St. James from 15 countries in Central Asia, including Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan for a celebration of spring at the Institute of Directors London’s Pall Mall.

The late Sir Eldon Griffiths, the Conservative Member of the British Parliament who chaired the British-Iranian parliamentary group, recalled meeting painters, writers, bankers and businessmen at her dinner parties, in his book “Turbulent Iran: Recollections, Revelations and a Proposal for Peace” (2006).

In the chapter “A Red-Haired and a Blue Marchioness,” he described her elegant dinner table, heaped high with fruits and flowers that characterize Persian hospitality. “Once the table was cleared, I was hauled up on to its polished top and coerced into trying to dance as Homayoun pirouetted around me to the sounds of a zither and tambourines,” he recalled.

Sir Eldon describes her as “more than a pretty face.” He recounted how Homayoun posed as a journalist in 1978 to become one of the few women granted an interview with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in Neauphle-le-Château, Paris.

“She arrived at his office without a headscarf and was told by his staff to cover herself. Homayoun refused until the Ayatollah persuaded her with the unassailable argument, ‘You are most welcome in my house. As in yours, we ask our guests to observe the customs of the host.’ On her departure, forty minutes later, Khomeini is said to have commented: “This woman is a danger to every Iranian man between the ages of eighteen and eighty.”

Babak Emamian of the British Iranian Business Association praised Lady Renwick’s pragmatic approach to issues. “She never claimed to be a politician, businessman, academic or philosopher,” he said, adding that her decisions and actions proved to be “much better than most.”

Lady Homayoun Renwick is survived by her son, Shahriar Mazandi, and her daughter, Yassemine Mazandi Castilla.