By Nazanine Nouri

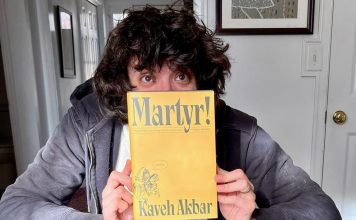

The critically acclaimed Iranian-American poet Kaveh Akbar has just released his debut novel “Martyr” — the story of a young man who mourns the death of his mother in the accidental U.S. downing of an Iran Air flight.

The novel’s fictional events are set in motion by the real-life tragedy of Iran Air Flight 655, which was accidentally shot down by the U.S. Navy in 1988, during the Iran-Iraq war, killing all 290 passengers.

“I have always been fascinated by this event, and nobody in America knows about it,” Akbar told PBS NewsHour in a recent interview.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Kaveh_Akbar_cropped.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Description: Poet Kaveh Akbar. Author:Birbiglebug. ” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”WikimediaCommons: This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/WhatsApp-Image-2024-02-29-at-19.01.48.jpeg” panorama=”off” credit=”KL./” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

“You hear a number like 290 people were killed on board. If that number was 289 or 291, it wouldn’t make a difference intellectually, right, for me? But that one life, every character in the book, their life is shaped by this event.”

“Martyr!” is the story of Cyrus Shams, an Iranian-American poet who mourns his father’s death — a father who brought him to the U.S. as a baby, after his mother was killed on board the commercial airliner, a tragedy that shattered the Shams family.

His father worked in an industrial poultry farm and only lived for his son — a son whose mother’s tragic end has filled him with hopelessness and the feeling that her death was meaningless.

Cyrus has struggled with depression, insomnia and addiction his whole life, and is now living in an Indiana college town as a recent graduate, recovering from alcoholism and opioid addiction.

“All that holds him back from the abyss is an obsessive desire for his life and his death to matter,” wrote the New York Times. “He wants the opposite of his mother’s meaningless end, to sacrifice himself for a higher cause.”

Fascinated with martyrdom, he delves deep into people whose deaths did not go unnoticed, covering his apartment with photos of Bobby Sands, Joan of Arc, The Tiananmen Square Tank Man, and his parents on their wedding day. His project finds focus when he comes across Orkideh—an Iranian artist with terminal cancer who has moved into the Brooklyn Museum to stage her death—and travels to Brooklyn to interview her.

Speaking in the Barnes & Noble podcast series Poured Over, Akbar said he had forever had this idea of “an artist performing their own dying, in a sort of Marina Abramovic ‘artist is present’ kind of performance piece, and fiction is a place where you can just put such ideas into action without actually having to live them—you can kind of play out these thought experiments.”

“So, that was the precipitating nugget,” he added, “the precipitating kernel, the Iranian culture of martyrdom, specifically Shia Islam, especially as it is practiced in Iran, and the way that the current regime weaponizes the theological meanings of the word has been interesting to me forever.”

Akbar was born in Tehran in 1989 to an Iranian father and an American mother and moved to the United States at the age of two, first to Pennsylvania then to Jersey, Wisconsin and Indiana. He holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree from Purdue University, a Master of Fine Arts from Butler University and a PhD in creative writing from Florida State University.

Kaveh sees himself in Cyrus: “I was born there, raised here,” he told PBS, referring to Iran. “I love Ferdowsi, I love the Shahnameh. I love Hafez. I love Islam. But I also love Erykah Badu. I love EPMD and Vogue and Sonic Youth. And it has shaped the person that I am.”

Like Cyrus, Kaveh was an alcoholic by the time he was in college, starting drinking as a teenager—a self-destructive period that nearly destroyed him. He has been sober for nearly 11 years.

He told PBS that all of his work “orbits recovery in one way or another, explicitly or implicitly. Every experience of my life, every interaction that I have, my spouse, my dog, my teaching position, the fact that we sit here right now, is predicated on the fact of my recovery, right? Had I not recovered I wouldn’t have any of this.”

“Of course, I’m no less an addict today than I was 11 years ago,” he added. “I just have better tools with which to cope with it…If I take the first drink or if I snort the first line or whatever that thing is today, all bets are off, right? The partition between me and an early preventable death is a little bit thinner than it is for a lot of people. And that is true for Cyrus.”

Akbar is a faculty member at the University of Iowa where he is the director of the English and creative writing major and also teaches in the low-residency MFA programs at Randolph College and Warren Wilson College.

He has made a name for himself as a poet with the chapbook Portrait of the Alcoholic (2017); Calling a Wolf a Wolf (2018); Pilgrim Bell (2021); and as editor of The Penguin Book of Spiritual Verse: 110 poets on the Divine (2022). Since 2020, he has served as poetry editor for The Nation—a position previously held by William Butler Yeats, among others. His poems have appeared in The New Yorker, the New York Times, the Paris Review, Poetry, Best American Poetry, and PBS NewsHour.

Akbar has received numerous honors, including the Levis Reading Prize, the 2016 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship, Pushcart Prizes, and a Civitella Ranieri Fellowship. In 2014, he founded the poetry interview website Divedapper to give contemporary poets a space to share their stories and writing.