By Cyrus Kadivar

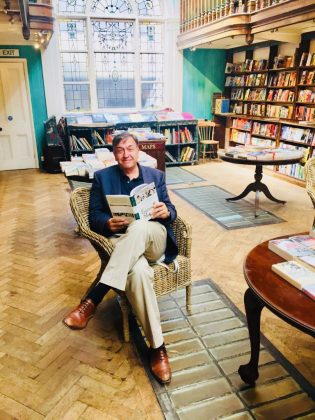

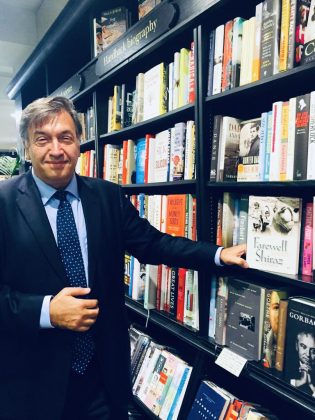

[Cyrus Kadivar is the author of Farewell Shiraz: An Iranian Memoir of Revolution and Exile. The views expressed are his own.]

When I published my memoir Farewell Shiraz in the autumn of 2017, my readers seemed to relate to the glamorous world described on its pages, violently destroyed by a revolution led by Ayatollah Khomeini, an old and bitter cleric who had returned from exile in France in February 1979 to be acclaimed like a messiah by millions of hysterical followers. Within a fortnight, he had toppled the last government of the Pahlavi dynasty, and replaced the monarchy with an Islamic Republic. And yet, eight years earlier in 1971, near my city Shiraz, at Pasargadae and Persepolis, the last Shah of Iran and his court had hosted a party attended by many world leaders honouring 2,500 years of the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great.

At the time the country had seemed so stable, forward-looking, prosperous, strong, and eternal. By the middle of 1978, the same country which had enjoyed an economic boom was edging towards a recession. Mohammed Reza Shah’s attempts to liberalize his once autocratic regime, the inept handling of the economic and political crisis, and foreign pressure and meddling by his Western allies to urge him to give up power had emboldened the growing left-wing and religious opposition to his personalized rule, and proved too strong to fight off.

I kept a diary in those tumultuous days, as wild mobs set fire to cinemas, restaurants, government offices and businesses. There was sporadic chaos in the lawless streets of Tehran and major cities, including my hometown, Shiraz. Martial law and concessions failed to end the cycle of riots and strikes that crippled imperial rule.

Within a month of the Shah’s departure and the Ayatollah’s return, the military and the police had capitulated. The mausoleum of Reza Shah, the father of modern Iran, was demolished, and all of the statues of his son were pulled down from their pedestals.

In the torturous weeks and months that followed, Iran descended into an abyss. Former military and civilian officials in the imperial regime were arrested by bearded, self-styled, gun-toting revolutionary vigilantes who handed them over to the Islamic courts to be judged as ‘corrupt elements on Earth,’ upon which they were shot by a firing squad, and their bodies photographed for the newspapers. Westernized professionals were purged. Wealthy industrialists had their assets confiscated. The once vibrant lifestyle of middle-class Iranians vanished almost overnight. Under Khomeini, pop music, singing and dancing, alcohol, gambling and chess were declared sins punishable by flogging.

Worse still, Iranian women, once the freest in the Middle East and active in all walks of life, were fired from their posts. Their basic rights were severely curtailed and degraded, and they were forced to wear the hejab by a medieval theocracy that also persecuted ethnic and religious minorities. Marxists, liberals, dissident intellectuals and secular politicians who had placed their faith in Khomeini’s false promises of democracy, political freedoms and human rights were hoodwinked and sidelined as religious zealots seized power.

My family and I were among the millions caught up in this cataclysm. It was time to leave our country as so many others had done before us. We left behind many things: our city, our lovely house, our life, friends and relatives. As a Western-educated surgeon married to a French woman and the father of three children, my father was determined to get his family out of Iran and over to Paris.

Even as we flew away, we told ourselves that it would be temporary. We hardly took anything with us into exile but a few suitcases, two Persian rugs, a book or two, and our photo albums. Throughout the trip, I kept thinking of my last summer listening to the Iranian pop superstar Googoosh, falling in love, partying, and splashing about in our pool with friends – enjoying what was left of our evaporating youth.

Uprooted at 16, I spent the next four decades living between the U.S. and Europe, finally settling down in London where I got married and made a career in banking, journalism, and risk management. Like so many other compatriots in exile – our numbers are estimated at 3 to 4 million — I attended Persian events in order to stay connected with Iran. To calm my soul, I consulted the works of the Shirazi poet Hafez, indulged in nostalgia for the happier times before I emigrated to the West. Then, just before my 30th birthday, a cousin mailed my teenage diaries, which she had smuggled out of the country, allowing me to recreate my shattered world.

In 1999, while writing my book, I visited the Al Rifaie Mosque in Cairo and stood before the last Shah’s tombstone. Beneath the marble lay the remains of a monarch whose patriotism and high-flying ambitions for his people had come to naught. His exile and death from cancer seemed to be the final curtain descending on a personal drama in my own life. Twenty years after the Revolution, I felt that I had reached the end of history.

With the Shah and his nemesis Khomeini long gone, I should have turned the page and moved on. Instead, I was beset by more questions than answers. Iran under the Pahlavi monarchy had in half a century emerged from feudal slumber and backwardness to become one of the most rapidly modernizing nations in Asia and by far the strongest power in the Persian Gulf region. Living standards were rising, as were oil revenues, and the future seemed so bright. No wonder the Iranian Revolution came as a shock to many.

After the Crash of ‘79, my country had seen nothing but war, political repression, terrorism, international infamy, corruption, and economic mismanagement on a colossal scale. How had we come to this? While historians tried to determine the roots of the collapse, offering their own theories, my quest brought me into contact with ordinary Iranians, but also men and women who had partaken in nation-building, socio-economic and military development, cultural life, and diplomacy. I tracked down a dozen key witnesses to the last days of the empire: generals, ministers, academics, revolutionaries and the former Empress.

Thus, when I finally shared my story with the world, I had a sense of closure and the relief that a weary traveller has at the end of a long journey. While I kept the hope of seeing Iran again, I prayed that I would live long enough for it to happen. A relative brought me some soil from Shiraz and lamented over how much the city had changed and grown – and how unhappy people were.

Then, suddenly, everything changed. The murder of Mahsa Amini, a young Kurdish Iranian woman kidnapped by the hated morality police for not wearing her head covering properly in September 2022 unleashed a tsunami of protests against the rule of the mullahs. Fearless young girls burned their scarves and brave men joined them ready to die for their slogan: Woman, Life, Freedom.

More than three months since Iran erupted, I have been glued to the television networks, social media, and the phone, following events in my homeland. I have joined thousands rallying in Trafalgar Square waving the old Lion-Sun flag of pre-revolutionary Iran, and signed petitions against the atrocities committed by a barbaric pseudo-Islamic regime that has so recklessly damaged Iran’s glorious heritage and image as a cradle of civilization.

Never has the Iranian diaspora seemed so united, outraged, and hopeful over the massacre of some 500 young people (including 30 or more children) and the arrest of 20,000 protesters. Two young men have been hanged and more are on death row. And yet the protests continue, with pictures of Khomeini and of the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei being torn down in Tehran and hundreds of cities, towns, and villages in Iran.

Today, Iran, a land of 85 million people (half of them women), and the rest of the world are witnessing an epic battle on the scale of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, pitting two powerful and irreconcilable forces against each other: a mostly young, secular and modern population, proud of its 5,000-year-old civilization and impatient for change; versus a discredited, isolated and fossilized theocratic regime, sworn to holding on to power with its hands steeped in the blood of innocents after 43 years of brutal existence.

As I write these words, I am filled with hope that the great people of Iran will overthrow not only the Supreme Leader, but the entire regime with its velayat-e faqih (a Shia Islamist system of governance which justifies the rule of the clergy over the state in perpetuity), the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps and the Baseej forces responsible for the indiscriminate killings of our young people.

Be in no doubt that the years of suffering will end, and that light will conquer darkness. For those who think that Iran is not ripe for democracy, I say listen to the chants of the youth and the clear message that they do understand the meaning of democracy and yearn for it. When that will happen is anybody’s guess, but it will.