Nazanin Afshin-Jam, the prominent international human rights advocate and author, has recently proposed a plan to pave the way for freedom in Iran. She believes that achieving meaningful change requires a coherent and sustainable strategy, which she envisions through a transition commission called the Iran Transition to Democracy Commission.

Afshin-Jam’s impressive track record includes a campaign in 2007 to save Nazanin Fatehi, a teenage girl facing the death penalty. In her book, “The Tale of Two Nazanins,” Afshin-Jam shared the insights and strategies that fueled the successful campaign.

Nazenin Ansari, the managing editor of Kayhan Life, interviewed Nazanin Afshin-Jam.

What inspired your plan for the Iran Transition to Democracy Commission (ITDC)?

First, it’s important to stress and clarify that the ITDC is not an established or existing entity but rather an idea intended to spark dialogue and gauge its feasibility. The concept draws from years of grassroots efforts and collaborative models within the Iranian diaspora.

The inspiration for the ITDC arose during a conversation with my longtime friend. We were sharing concerns reflecting on the increasing divisions within the Iranian community and grappling with how to overcome obstacles to help our compatriots who are increasingly facing unlivable economic hardship, suffocating from air pollution and environmental degradation, and suffering from severe human rights abuses and societal repression.

Iran’s issues are dire and urgent, and the demise of the regime is in sight. There is absolutely a need for a readiness plan in place.

We concluded that maybe the answer was staring us in the face. Perhaps the collaborative model in the network we belonged to, focused on expertise, project management, and shared goals, could be applied more broadly to find a solution for the transition to democracy.

We realized that we can achieve remarkable outcomes when we park our politics, ideologies, and preconceived notions at the door and simply concentrate on projects using our individual skills and abilities. Therefore, the same may be applied to a non-partisan commission to accomplish the required tasks to get us from point A to point B in a transitional period for Iran.

Could the concept of ITDC be seen as aligning with a specific political framework?

Not at all. As I mentioned earlier, the ITDC is purely a conceptual framework at this stage. Its purpose is not to seek political power or function as a political party but to develop a comprehensive plan, based on experts’ perspectives, that facilitates a sustainable and orderly transition from the current regime to a democratic system. The idea is to prevent chaos and bloodshed, and uphold the principles of democracy by ensuring that the people of Iran have the ultimate authority to choose their government.

For example, during the pre-transition phase, the ITDC could focus on forming specialized teams to manage key sectors, including security, humanitarian relief, and economic stabilization, and develop contingency plans by predicting, pre-empting, and preventing anticipated potential challenges such as economic instability and unrest and response to regime hostilities, and plan actionable solutions.

For the immediate aftermath of a systematic change, the ITDC’s responsibilities could provide expertise in maintaining public order, ensuring the safety of citizens, and preserving the continuity of essential services. It could also play a critical role in stabilizing the economy to prevent financial collapse and ensure the functionality of financial systems. A cornerstone of its mission would be to prepare the country for free and fair elections, laying the groundwork for a democratic future.

ITDC is envisioned as a non-partisan commission or task force with a temporary mandate. Once its objectives are achieved, namely, providing advisory guidance to the nation throughout the transition and enabling Iranian citizens to vote in a free and fair electoral process, the commission will be dissolved.

You proposed, “Initiatives such as rotating leadership roles would promote shared responsibility and balanced representation, fostering trust and collaboration within the group.” What do you mean by “rotating leadership”?

Ultimately, the Commission must determine the best course of action. However, I proposed the possibility of a rotating chair position to promote fairness and balance. While technocrats would be elected based on expertise, ensuring that neither personal nor political biases influence decision-making is essential.

A rotating chair structure can help prevent any political ideology from dominating the process or any individual from accumulating excessive power. The chair’s primary role would be as a neutral moderator, facilitator, and project manager, ensuring that teams remain focused, meet objectives, and adhere to deadlines.

Could the ITDC collaborate with organizations like the National Union for Democracy in Iran (NUFDI) with its “Iran Prosperity Project” and the “Iran Phoenix Project”?

The commission should actively consult with experts, organizations, and institutions to ensure a well-rounded approach. Ideally, it would collaborate and hold meetings with diverse groups, particularly those that have already developed detailed roadmaps and action plans for the critical “first hundred days” following the regime’s fall. This would give the commission more confidence in planning the first 365 days. Engaging with these groups would enable the commission to consolidate insights and present the most effective action plan.

Apart from introducing the concept of the ITDC, you also established a network of Iranian diaspora groups in 2023. What is the latest update on this network?

Thank you for clarifying that ITDC is only an idea and completely separate from the decentralized network I help facilitate. They have not been consulted on the idea yet, so it would be unfair to link the two.

After Mahsa Jina’s death, countless activists united and formed groups. However, I noticed instances of duplicate efforts and overlapping agendas among them. For example, several groups independently created databases of political prisoners and sought political sponsors from Western countries.

In January 2023, I decided to bring them together for a meeting. Gradually, the groups themselves began suggesting other organizations and individuals to include. Today, the network has approximately 100 Iranian diaspora groups and a few hundred exceptional activists. Each group is connected to an even broader network inside and outside Iran. This decentralised network is based at the grassroots level and comprises various Iranian professionals worldwide with expertise across many fields.

Although we avoid discussing political affiliations, I know that individuals within the network span the full political spectrum from right to left. Members form affinity groups and work on projects between our monthly meetings.

The goal has been to create synergy, streamline work, increase efficiency, and foster a sense of trust and collaboration. Feedback is gathered through monthly surveys to ensure the network remains responsive to members’ needs and campaigns and that they have a say in the direction of the network itself.

Over time, this collaborative approach has cultivated a strong sense of community, mutual respect, and measurable success across the network and its connected communities. We hope the network can help empower and share resources, amplify the visibility of their projects among media outlets, think tanks, and political organizations, and ultimately maximize their collective impact.

These diverse non-political groups are united by their shared commitment to core values: a profound love for Iran and its people and an unwavering dedication to freedom, democracy, human rights, and prosperity for their homeland. Together, we have demonstrated that we can achieve extraordinary results with unity, solidarity, and a focus on shared goals without allowing partisan politics to divide us.

Can you highlight some successful joint projects they have undertaken?

Members of our network, along with their extended networks, have contributed to significant successes. These include lobbying to have the IRGC listed as a terrorist organization in Canada, nearly securing this designation at the European Council, and achieving the removal of the IRI from the UN Commission on the Status of Women, an unprecedented move.

We’ve also seen the unanimous consent motion passing the Toomaj Sanctions in Canada’s House of Commons and Senate. (Rapper Toomaj Salehi was sentenced to death in Iran for his songs supporting the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. In June 2024, Canada’s Parliament passed the “Toomaj Sanctions,” urging the government to impose targeted sanctions on members of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Courts. )

We also convened a special UN session on Iran, which led to the establishment of the UN Fact-Finding Mission on Iran. Recently, we successfully advocated for the mission’s extension, supported by a delegation of Iranian diaspora experts and regime survivors formed through our network.

Beyond political victories, our network has helped refugees find safe asylum, addressed some survivors’ medical needs through collaborations among connected medical groups, helped introduce groups to the joint campaign against executions and the End Gender Apartheid campaign, and galvanized communities to push governments to cancel regime-sponsored events, sanction or deport regime officials, and facilitate access to tools like Starlink and VPNs within Iran.

This collective spirit of purpose and determination is the key to advancing our cause, as demonstrated by our community over the past few years. Who can forget the global outpouring of solidarity after Jina Mahsa Amini’s death? Fifty thousand people gathered in Toronto, 80,000 in Berlin, with tens of thousands more in cities worldwide. The hashtag #MahsaAmini reached 500 million tweets, setting a Twitter record. Iranian women were named TIME magazine’s Persons of the Year. Shervin Hajipour’s “Baraye” earned an Emmy in a category created especially for it.

The two most prestigious human rights prizes, the Nobel Peace Prize and the Sakharov Prize were awarded to Narges Mohammadi and Jhina Mahsa Amini and the Women, Life, Freedom movement. Political leaders cut their hair in solidarity, lit up monuments, renamed streets after Jina Mahsa, and invited diaspora advocates to prominent forums like the Munich Security Conference and the World Economic Forum, displacing regime officials.

These accomplishments and many more were possible because people set aside their differences and political affiliations, echoed the people’s wishes in Iran, and acted in unity.

What prompted you to turn off the reply option on your Twitter account?

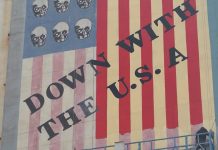

I decided to turn off the reply option over a year ago, primarily because I noticed that Iran’s cyber army has hegemony over the Twittersphere and is increasingly hijacking opposition activists’ messaging. The regime uses a cyber army consisting of thousands of online operatives to push their narrative.

By disabling replies, I was able to reclaim my platform as a space for disseminating news and content that aligns with my goals rather than allowing it to be influenced by these orchestrated distractions. My audience includes politicians, policymakers, think tank members, and journalists, and I did not want them to be distracted by these fake narratives and disinformation.

I can open the comments when I need feedback or input on a particular issue. In the meantime, I have direct access to committed advocates outside Iran and inside the country, allowing me to gauge sentiment and gather insights accurately. Readers could share their opinions through reposts, the comments section under the JP article, and the Kayhan London article. Unfortunately, most comments were not constructive criticisms of the ideas behind the article but rather baseless personal attacks, including very sexist commentary.

You’ve steadfastly advocated human rights in Iran for over two decades. What drives your commitment? Do you have any political ambition when Iran is free from this regime?

I have no political ambitions in a free Iran, though I have always had a deep interest in international politics. My academic journey reflects this passion, with degrees in political science and international relations and a master’s in diplomacy focusing on international conflict management. In 2007, I was approached to consider running as a Member of Parliament in Canada before I met my husband, a politician. However, I chose a different path that allowed me to remain independent and focus on humanitarian work, human rights, and the pursuit of democracy.

Nothing is more important to me than freedom, and nothing moves me more than alleviating human suffering and confronting injustice. This commitment has been the thread running through my life.

From volunteering at the food bank as a child and starting a global issues club in high school to volunteering as a global youth educator with the Red Cross during university and into my adult years, I have dedicated myself to helping the world’s most vulnerable. This includes fighting for the rights of Iranians to have the same freedoms and opportunities I was fortunate to experience growing up in Canada.

This work is more than a mission; it is a calling and a passion that stems from a profound love for people, their well-being, and their ability to realize their full potential. I will never forget the anguished voices of mothers who called me while I ran Stop Child Executions, pleading for help as their children faced death row in Iran. Those moments are etched in my heart, strengthening my vow to do all I can to contribute to the path of freedom for Iran.

Today, as a mother of three young children, my time and attention are often devoted to them, yet my dedication to these causes remains unwavering, driven by the same love, hope, and belief in a better future for all.

Are you receiving funding for your activities?

Not only am I not being paid for my efforts, but I have personally covered many of the costs associated with my volunteer work for Iran. This commitment involves financial sacrifices and the invaluable time I spend away from my family and children to fulfill this calling.

My flight and hotel accommodations are sometimes covered when I am invited to speak, but I often pay my travel expenses. With one exception, all my speeches and work related to Iran have been unpaid since my involvement with Woman Life Freedom.

A company invited me to speak about Iran and insisted on paying me as their protocol, despite informing them that I would not accept payment for anything related to Iran. In that instance, I donated half of the honorarium to victims of regime brutality inside Iran. The other half went towards the formation of a website platform featuring a database of political prisoners in Iran and their political sponsors in the West.

The platform started what would be known as the Iranian Justice Collective, an advocacy organization (IJC). I am one of the founding members. It has not fundraised or received any external funding. All our activities have been from our pockets, including two separate ‘Hill Days” where we met close to a hundred members of parliament and senators. On one occasion, we organized a meet-and-greet for the Iranian community with members of parliament, and members of the community kindly helped cover the event’s expenses. Other than this, there has been no exchange of funds.

My former organization, Stop Child Executions, a 501C3, only accepted private donations to run campaigns to free children from imminent execution, like Nazanin Fatehi. Everyone, including myself, was a volunteer and was never paid for our work. Even in our campaigns, we would run short of funds and pay out of pocket.

For example 2008, I organized the Ahmadinejad Wall of Shame rally in New York outside the United Nations. My family and I paid for the stage, sound system, permits, all the displays, and props, not to mention our flights and hotel, with little contribution from others.

In 2014, I launched The Nazanin Foundation, a registered charity to help vulnerable women and children worldwide and empower young girls. To kickstart the fund, I donated over $10,000 out of my pocket. We held one fundraising event in Toronto. The entire funds went to 4 places: Omid Foundation to help with vocational training of vulnerable girls in Iran, PEN Canada for the “Iran Emergency Fund,” Tearmann House, a local women’s shelter for women escaping domestic violence in Nova Scotia, and Plan International to put impoverished children in school.

I’m proud that we could cover the expenses of a girl in Kenya from childhood until her 18th birthday when she completed high school. This work was entirely voluntary.

I am blessed to have a husband who works full time and has supported our family while allowing me to volunteer full-time for Iranian causes and humanitarian work. I could not do my work without his financial generosity and caring for the children when I am away.

There is no shame in Iranian groups fundraising for our shared cause. As a community, we must move past the stigmas surrounding fundraising. If we are serious about this revolution for a complete change in regime and confronting the regime with billions of dollars at its disposal, we will need substantial resources. To be effective, initiatives like ITDC and others require funding, and the professionals involved should be fairly compensated so they can leave their current professions and dedicate themselves fully to this critical work.

You were crowned Miss Canada in 2003 and finished as the first runner-up at Miss World. How has this experience influenced your advocacy work? Have you encountered any challenges along the way?

When I entered the Miss Canada competition, I was already working as a youth facilitator with the Red Cross, educating others about critical humanitarian issues such as the crisis of landmines, the cycle of poverty and disease, natural disasters, and children affected by war. As I reached classroom after classroom, I realized these issues demanded a broader audience. Earning a title could provide a stronger platform to amplify my advocacy efforts.

Participating in the pageant helped and hindered my mission to effect change. On one hand, it helped draw significant media attention to the causes I deeply cared about. For instance, when I launched the “Save Nazanin” campaign to help rescue a teenager and victim of attempted rape who was on death row, the media spotlight facilitated access to critical political networks. It opened doors to parliaments in Europe and Canada, NGOs, and international institutions like the United Nations.

On the other hand, the title occasionally served as a barrier. Persistent stereotypes about pageant titleholders persist, and some struggle to see beyond those preconceptions. However, I’ve always believed in the power of the Miss World motto, “Beauty with a Purpose.” This initiative has raised significant funds, including one billion dollars, for children’s charities worldwide.

I am proud of my involvement and the work I’ve contributed to help children in countries like China, Ethiopia, and beyond. Unfortunately, these stereotypes are sometimes weaponized against me. For example, scroll through the comments on the Kayhan social media page under my article in the Jerusalem Post or its X post. You’ll see sexist remarks even by some women cherry-picking my pageant title in an attempt to delegitimize my achievements. They overlook the broader scope of my work: my human rights awards, my honorary Doctorate of Laws, my authorship, my position on various boards, and my role as a dedicated mother.

Those who chant “Woman, Life, Freedom” must understand that these words are not just slogans but require action. True liberation is about rejecting outdated biases and embracing the depth of women’s contributions in all their forms.

Do you see yourself living in Iran in the future?

One of my greatest dreams is to travel across Iran with my husband and children and meet many Iranians and family members I have spoken to only by phone. I long to see the places my parents often talked about, the ones that shaped their childhood memories. I dream of standing where they once stood, walking in the footsteps of my ancestors, and visiting Persepolis and the mausoleum where my grandparents and other relatives are laid to rest.

While my heart swells with pride for my Iranian heritage, Canada is where I’ve grown up since I was 2 years old and where we’ve built our life, so the probability of living in Iran is low.

Still, what happens to over 80 million people in Iran profoundly matters to me. Ensuring that half the population can escape gender apartheid and that young girls are free to pursue their dreams in sports, professions, and love deeply matters to me. As a Christian, it deeply matters to me that other Christians and religious minorities can practice their faith without fear of persecution.

Seeing one of the wealthiest countries in the world become a place where no child is forced to climb in and out of garbage cans instead of attending school deeply matters to me. The sight of the scars on my father’s back after being tortured and almost executed by the regime will never escape me. Witnessing an end to executions, torture, and other inhumane punishments deeply matters to me.

The safety of Canadians and people across the world affected by the spread of Islamist ideology, violence, and extremism stemming from the current regime deeply matters to me. Ending the funding and support of terrorist factions and addressing the existential threats faced by Israelis and other global citizens deeply matters to me. While Iran is far geographically, it always remains close to my heart.

Any final thoughts?

People are hungry and without homes, shelter, jobs, or electricity. Our identity politics and name-calling have no place on their empty “sofreh” (the spread on which plates of food are served). What our nation needs is unity, compassion, and action.

Regime Change Is Only Solution For Iran, Say DC Conference Speakers

The West Must Not ‘Bank on the Iranian Regime,’ Warns Renowned Journalist Amir Taheri

Prince Reza Pahlavi : ‘The Alternative to the Islamic Republic is the Iranian nation’