By Ahmad Rafat

Arash Sobhani is the founder of the pioneering Iranian rock group Kiosk. An architecture graduate, he formed his band before moving to the U.S. Kiosk was one of the prominent bands in the Iranian underground music scene.

Sobhani and Kiosk continued their musical collaboration after relocating to the U.S. While pursuing a career in music and architecture, Sobhani started working on television production a decade ago. He presented several programs for Voice of America (VOA) and MBC Persian.

Sobhani has recorded 10 albums and recently released his first film, Payan-e Shirin (“Sweet Destiny”), the first-ever musical in Iranian cinema. The film is premiering on VOA on Aug. 20., and will be available soon afterwards on sweetdestinythemovie.com, a website designed to showcase the film. The band will donate all proceeds from the film to Iran Human Rights Organization, whose primary aim is to eradicate capital punishment.

Writing in English about his film “Sweet Destiny,” Sobhani said: “In 1852 a young man is ‘blown by a gun’ or executed by cannon [fire] in Iran, from the incident remains a rare old photo, this photo is the start and the center of a unique journey. A journey that revolves around individuality, identity, and women’s rights.”

Kayhan Life’s Ahmad Rafat recently interviewed Arash Sobhani.

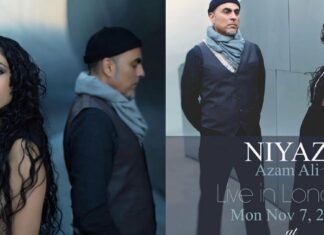

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/aea297af-1292-48cc-ba2e-09196e8d0c43.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Kiosk Band Founder Arash Sobhani (R) with Kayhan Life’s Ahmad Rafat (L). KL./” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

While pursuing your musical activities, you recently embarked on an extraordinary endeavor: producing a musical film. It is a Persian-language rock musical titled “Sweet Destiny,” and it is about Iran. What prompted you to make a rock musical film?

I have been thinking about it for a long time. We have always wanted to tell a story since forming Kiosk and releasing music albums. We did not want our songs to be a series of standalone and unrelated stories. Our previous album contained a different story. Nowadays, no one is producing full albums but only singles. For me, however, an album encompasses a chapter of my life and thoughts.

Old photographs inspired this story. Such pictures have always fascinated me, because they reflect the past and influence the future. These photographs formed the basis for our story, and I thought it would be good to incorporate live-action and animation into the project.

As always, we first wrote the story and then asked our friends to help us bring it to life. It took a few years, but we finally completed the work and will release it soon. We are thrilled to have produced the first-ever rock musical in the Iranian cinema. We hope others adopt the same style of storytelling by combining music with visual media.

It must have been challenging to combine live-action and animation in the film.

It was difficult, and there were several challenging aspects to the film. The scenes changed constantly and quickly. The songs and old photographs join to tell a modern story, making it imperative to change these defined spaces because musical pieces do not aim to repeat the same story but to move the narrative forward.

The music must be pleasant and conjure up images in the audience’s minds without compromising the story’s integrity. While the animation is the core component of the project, we used a different technique for each song. As a result, we asked artists from different disciplines to help. We gave them creative freedom to work on the project. Various techniques have enriched the film and made it very different from other music videos.

Sweet Destiny connects past and present. It begins with an execution of a person whose innocence or guilt is unclear. Why did you start the film with that event?

Execution is a sensitive subject. You know this well since you have been [reporting] on this for years. Although we all know that execution is a crime, the topic is divisive and controversial. Discussions on the issue turn contentious almost immediately. I have always been alarmed by the high number of executions in the Islamic Republic.

I have also been concerned about how to treat this subject. I am fascinated by the thin line separating comedy from tragedy. It is challenging to portray a tragic event without overwhelming an audience, so people do not stop watching the film after a few minutes.

I am interested in persuading viewers to watch a painful narrative because it is imperative to contemplate such events. As you mentioned, the man’s identity, the charges against him, and why he was sentenced to death were not the film’s focal point. The film does not answer those questions because that is not the focus of the audience. Everyone had their reasons for wanting to execute that man.

I thought a look at the execution was a good point to start a dialogue on the subject, which is highly complex and not a black-and-white issue. A civilized nation must eradicate capital punishment.

A woman named Shirin features prominently in the film, even though we never actually see her. Although invisible, Shirin is present throughout the film. She has no civil rights, and that’s why no one can see her.

There are several layers in this film, one of them is the plight of women. The character Shirin is loosely based on the [tragic love story of] Khosrow and Shirin by [Iranian poet] Nizami [Ganjavi, 1141-1209 AD]. In the story, [Khosrow and Shirin] fall in love after seeing each other’s portraits. Women have always been depicted in the same way in Persian miniatures and stone reliefs. We do not see many variations in those visual representations.

The other issue is the concept of individuality in our country and the Middle East. People as individuals do not exist in that part of the world unless they support a football team or are members of a tribe or a religious sect.

An individual is not officially recognized outside those affiliations. We also wanted to highlight this issue for our audience. The narrative prompts the audience to think about Shirin, who is not seen but present throughout the film. She is the principal character that connects various aspects of the narrative.

Two people narrate the story, one of whom speaks in the ethnic Armenian dialect. What is the reason for that?

You have worked with Iranian and foreign media and know that it is next to impossible to translate some news about Iran into other languages, even though they are ordinary, daily occurrences for us Iranians. For instance, we read that no one can eat ice cream. We ignore the comment, thinking who would say such a stupid thing.

If we translate this into Italian, the audience cannot understand it. Also, we do not know where to start and how to explain this. That is why I thought it is better to use someone with a different perspective, like an individual with an Armenian dialect. We did not mean to imply that Armenians are not Iranian. The dialect provides a fresh viewpoint. The entire episode looks like a circus to that person who wants to get out of that horror show quickly.

The person’s camera counterbalances the cannon that is going to be used in the execution. They must shoot simultaneously. Both technologies come from the West. While the authorities favor some Western technologies like nuclear weapons, they are disinterested in others, including the camera or human studies. We have been dealing with this situation for the past 100 years.

The film’s title is ‘Sweet Destiny,’ but it begins with an execution, which is a horrendous event.

We did not want the film to end with a slogan.

But you wanted to keep the hope in the future alive.

Exactly, we wanted to give hope without disseminating slogans. We wanted to say that change is possible, like the scene depicting Hitler’s death in Quentin Tarantino’s “Inglourious Basterds.” The film fictionalizes history, but the audience rejoices in Hitler’s death even though it did not happen like that in real life. We wanted to convey the same feeling at the end of our film by saying that this dream could come true.

The principal problem for Iranian filmmakers working abroad is to find distributors, making it difficult for their films to be shown in cinemas. A few Iranians can see these films at festivals. Have you thought of ways to make Sweet Destiny available to more Iranians?

A Persian-language cable TV will broadcast the film on Aug. 20. We will also launch a website where people can watch the movie. However, the problem which you highlighted is serious. Although we want everyone to see the film, the proper way is for audiences to buy tickets.

Everyone, including people living in Iran, can watch the film on the website for free. However, we urge our audience to donate to Iran Human Rights Organization through the website and help eradicate capital punishment. I support the organization’s efforts to eliminate the death sentence from the law.

Our aim for making this film was to show that artists continue to work. I hope other artists support this and future projects.