By Adom Saboonchian

The acclaimed Iranian author and screenwriter Ghazi Rabihavi and the renowned theater actress Soussan Farrokhnia and director-producer Ethan Jahan recently collaborated on a video art project titled “Motherhood” which has now been published on social media.

Ms. Farrokhnia provides the voiceover and narration for the 17-minute short film, which deals with the current COVID-19 pandemic and the violent protests in November in Iran that left some 300 people dead and scores of others injured.

Mr. Rabihavi left Iran in the mid-1990s and has been living in London ever since. Several of Rabihavi’s plays have been translated into English and Dutch and staged in recent years.

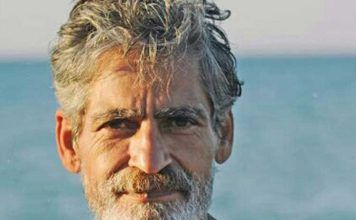

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ghazi-rabihavi.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Ghazi Rabihavi. Kayhan London” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Asked by Kayhan Life why he had selected the coronavirus outbreak and the violent protests sparked by the fuel price hike in Iran for his video art project “Motherhood,” Rabihavi said: “The film tells the story of a nurse who, while off work, witnesses a protester getting hurt in the street. The nurse’s mother pleads with her conscientious child to stay home. However, motivated by a sense of duty, the nurse rushes out of the house to help the injured protester, and tragically dies as events unfold.”

“We agreed that the main character in the story — who has been killed — should be a nurse, because nurses are the hardest-working and altruistic health professionals who risk their lives on the frontline to save others,” Rabihavi explained. “We are witnessing this all around the world today.”

The following is an interview with the artist.

The audience gets to know the nurse only through the words of the grieving mother, who has to overcome many obstacles to visit her child’s grave.

We deliberately did not clarify the nurse’s gender. The nurse could be male or female. It was challenging to write the screenplay in a way that kept the nurse’s sex ambiguous. We leave it to the audience to decide whether the nurse is a man or a woman.

Some people may conclude that the nurse is a woman, especially when the mother speaks of her child’s beauty. However, to a mother, her child is beautiful irrespective of the child’s gender or physical attributes.

The narrative makes the audience doubt their impression of the nurse’s gender. Ms. Farrokhnia’s narration and voiceover describe the family relationships, particularly between the nurse, the mother, and the uncle (on the mother’s side).

That’s right. The uncle is an essential character in the story because he is a teachers’ rights activist, even though we only see pictures of him. The story contrasts the values and principles of this family — which is a representative of millions of Iranians — against the oppressive regimes that brutalize their people.

In the story, the nurse’s mother says that she cannot understand people who, to get a better life, will commit robbery and murder. She wonders who these people are that stop at nothing to get what they want, while the nurse selflessly serves the public.

You superimpose and juxtapose real and symbolic imageries. For instance, in one scene, we hear the narrative voice about Shiraz wine over a photograph of Hafiz’s tomb and a clip of a red cloth moving mysteriously in the wind.

I must point out that Ethan Jahan did much more than just editing the film. He also selected and bought the copyrights of many of the photographs we used in the video. He spent many days compiling the images we used. He was the editor and producer of the film.

The late Kaveh Golestan (photojournalist and artist 1950-2003) and I collaborated on five or six art videos in the 1990s in Iran. Working with Ethan Jahan was, however, an entirely fresh experience. We did not have Photoshop back in the 1990s.

I had initially written the story for a play. But I adapted the screenplay for video after the COVID-19 lockdown.

We looked for a long time before finding the exact clip of a red cloth we wanted. Red symbolizes the life force. We have used it a lot in the video. The sequence showing a red rose flower opening represents the eternal spirit of the nurse. In contrast, a wilting red rose symbolizes death.

You have used Beethoven’s music in the video. Does it not clash with the imagery of Iranian sites and sceneries and prevent the audience from connecting to the narrative?

We did not want to move our Iranian audience emotionally by using familiar and sad Iranian music. The music in the video creates a sense of alienation. I use Western music, which is not as [culturally] familiar to Iranian audiences. I did not want the music to create a sad mood but rather to celebrate happiness. I used Beethoven’s music because 2020 marks the 250th anniversary of his birth.

The audience only hears the voice of the nurse’s mother, acted by Ms. Farrokhnia, who narrates the story. One gets the impression that she has not accepted the death of her child and continues to have conversations with the dead nurse in her imaginary world.

As far as a mother is concerned, her child never dies, especially if she has no other children. She will carry the memory of her child to her grave. Such women do things that other people may find strange, like washing the clothes of their dead child or speaking to him or her.

This video, however, sends a message to the oppressive regimes that mothers and people will keep the memories of their slain children alive forever, and will ultimately realize their goals and aspirations. These children are eternal, and the oppressors cannot destroy them.

The security forces have banned family and relatives of slain protesters from entering cemeteries where their loved ones are buried, but the mother avoids detection and visits the nurse’s grave. She sits by the headstone of her dead child and drinks a glass of wine. Intoxicated by the wine, she engages in an imaginary conversation with her child.

The mood should not be overly sad but to convey hope instead.

This article was translated and adapted from Persian by Fardine Hamidi.