[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#333333″ columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” disable_bgshading=”off” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off” aesop-generator-content=”Disclaimer: This asset – including all text, audio and imagery – is provided by The Conversation. Reuters Connect has not verified or endorsed the material, which is being made available to professional media customers to facilitate the free flow of global news and information.

“]Disclaimer: This asset – including all text, audio and imagery – is provided by The Conversation. Reuters Connect has not verified or endorsed the material, which is being made available to professional media customers to facilitate the free flow of global news and information.[/aesop_content]

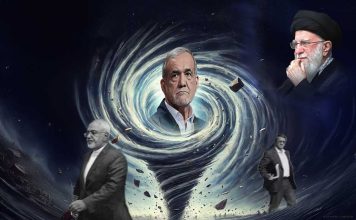

The Iranian government has announced several arrests in connection with the reported poisoning of more than 7,000 schoolgirls in more than 100 schools around the country. Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, has condemned the poisonings, saying perpetrators should be “severely punished”.

Yet other government messages are confused. The education department announced that girls who had been taken to hospital were suffering from “mass hysteria” and the education minister insisted that 95% of the girls were merely suffering “fear and worry”.

The available evidence, including reports that pupils detected a strange smell in their classrooms, suggests a number of mass gas attacks in Iranian girls’ schools. Dismissing this reality as “hysteria” is a futile attempt to absolve the state of its culpability.

The act of dismissing the suffering inflicted on Iranian girls as mere “hysteria” comes after a prolonged period of violent suppression of Iranian protesters over the past six months. The widespread protests were sparked by the murder of Mahsa Amini, a young Kurdish-Iranian woman who was fatally beaten by the morality police in September 2022 for wearing her hijab improperly.

Since the protests began, thousands of protesters – many of them women and girls – have been arrested and by the end of January it was reported that 41 people had been sentenced to death for protesting. Hundreds of people have been killed in the streets and many Iranian girls have reportedly been raped by security forces while in custody.

Reports of poisoning in girls’ schools – which had been a major centre of protests – began to emerge in November last year from the city of Qom, home to the most senior clergy in Iran. Girls were reported to be displaying a range of symptoms including difficulty breathing, burning sensations, vomiting and paralysis of the lower extremities. Speaking to the UK’s Guardian newspaper recently, a local journalist said: “One doctor told me that based on the symptoms they’re seeing, it’s likely to be a weak organophosphate agent”. Organophosphates are toxic chemicals often used as pesticides in agriculture.

The immediate question is whether these alleged poisonings are connected with protests in girls’ schools after Amini’s death. Young women have been particularly visible in what has amounted to a nationwide uprising against the Islamic Republic, which has as its slogan: “Women, Life, Freedom”.

Women’s Day Protesters Rally for Rights, With Focus on Iran and Afghanistan

While the supreme leader called the poisonings “unforgiveable” and called for the death penalty for perpetrators, the head of Iran’s judiciary threatened to charge anyone who “spreads rumours and incitement” about the issue. Consequently, numerous critics contend that the supreme leader’s proclamation is merely an attempt to gloss over or conceal the truth.

Despite these poisonings going on for several months now, there remains a lack of clear information about the circumstances of the attacks and the chemicals used. The lack of media freedom in Iran hasn’t helped. But the fact that the attacks have occurred throughout the country would suggest that whoever is behind them has access to a significant quantity of these chemicals and has the organisation to orchestrate such a large number of attacks across the country.

That’s why there has been increasing suspicion that either an extreme faction within the state is responsible, or that a state with 16 parallel security organisations to monitor every facet of life should be able to identify the masterminds behind these nationwide attacks.

Comparisons have been made with the shooting down by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) of Ukrainian airliner, Flight 737, in January 2020. Regime officials categorically denied responsibility for a week until emerging evidence compelled them to accept accountability.

Once the poisonings – and the treatment of parents who complained and were savagely beaten by regime security officials – went viral on social media and were picked up by international news outlets, the blame game began to unfold rapidly.

The president, Ebrahim Raisi, attributed the attacks to “foreign enemies” – a fairly typical response in Iran. The regime heavily relies on the abstract notion of a foreign enemy – usually America – to absolve itself of any responsibility. In this case Raisi was not specific about which country was behind the alleged poison attacks.

Exhibition on Iranian Women’s Protests Opens at Jerusalem Islamic Art Museum

But the issue is further feeding unrest in a country which remains on a knife-edge. Hundreds of thousands continue to protest against the state for political repression, corruption, and discrimination against women and ethnic minorities.

The problem faced by the Islamic Republic is that there is massive support for the protests. A leaked government poll from November 2022 found that 84% of Iranians expressed a positive view of the uprising and trust in the government and its media outlets has fallen sharply in recent years. More than 60% of respondents in an online survey said they wanted to transition away from the Islamic Republic.

Several observers have noted similarities to acid attacks carried out in 2014 when assailants on motorcycles threw acid in the faces of at least eight women who were driving with their windows down. One woman died, and the remaining victims sustained permanent physical impairment.

Following the acid attacks, thousands of people demonstrated in the city of Isfahan to express their horror and outrage. Many Iranians believe that the victims were targeted because they wore clothing considered by hardliners as “inappropriate”. So the arrest and murder of Amini for not wearing her hijab in the approved manner has resonated in the minds of many ordinary Iranians.

Nobody was held accountable for the 2014 acid attacks. But things are different now. Back then, the state did not face the same crisis of legitimacy as it does currently. Now, a protest that began in defence of women’s rights, secularism and democracy has spread across almost all of Iranian society encompassing men and women young and old, urban and rural, workers and intellectuals. Although the Islamic Republic is accustomed to internal and external upheavals, it is currently facing an existential crisis.

By attacking girls in their schools the only possible motive must be to perpetuate a climate of fear in Iran. Perhaps fear is the last weapon in the arsenal of a regime that appears to be struggling for survival.