By Nazanine Nouri

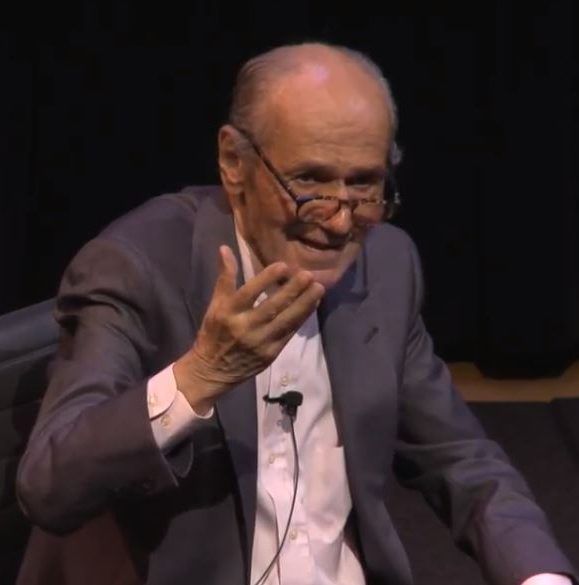

The Iranian-born, American sculptor Siah Armajani has died of heart failure in Minneapolis at the age of 81. The artist’s death was announced on social media by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which coproduced his 2018 retrospective “Siah Armajani: Follow This Line” with Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center.

“We are deeply saddened by the passing of #SiahArmajani, known for his wry humor, gentle nature, and deep conviction in the revolutionary power of art as a form of civic engagement,” The Met said in its Twitter announcement. “His social justice and political activism in Iran led to his forced emigration to the US in 1960.”

Armajani was born in Tehran in 1939 into a wealthy family of prominent textile merchants. As a young man, he was a supporter of the first democratically designated prime minister of Iran, Mohammad Mossadegh. He circulated “night letters” or political leaflets under the cover of darkness, outlining the democratic, secular vision of Mossadegh’s party, the National Front. His works from the late 1950s, which took the form of these “night letters,” contain subtle messages such as “Mossadegh’s way,” “Oil is ours,” and “Freedom is ours.”

Armajani studied philosophy at the University of Tehran, but left in 1960 at his family’s urging to avoid arrest for his political activity. He moved to Minnesota where he continued his studies at St. Paul’s Macalester College. The “Twin Cities” — as Minnesota is commonly known — would remain the reclusive artist’s home for the rest of his life.

Armajani “was mesmerized by the logical purity and physical power of America’s geometrically absolute and structurally straightforward farm buildings, grain silos and covered bridges,” wrote the New York Times in 2002.

“You can walk around a barn and into it and see exactly how it’s put together and how it’s supposed to function,” the artist told the paper in an interview. “There’s no concealment. And that is what art should be.”

Iranian Master Sculptor Siah Armajani to Exhibit at Met Breuer in February

Long underrecognized, Armajani was the subject of a first major retrospective in the United States at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in September 2018. Organized with New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Siah Armajani: Follow This Line” traveled to the Met Breuer — the contemporary-art arm of the Metropolitan Museum — the following year.

The artist is best known for his large-scale, politically resonant works that merge sculpture with architecture. He created bridges, gazebos, gardens, and reading rooms for outdoor public spaces across the United States and Europe. He designed the Olympic Torch for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, as well as the Lighthouse and Bridge on Staten Island. In Minneapolis, his landmark 375-foot Irene Hixon Whitney Bridge (1988) connecting Loring Park to the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden was restored in advance of his 2018 exhibition.

Armajani’s remarkable career in public sculpture was guided by his manifesto: “Public Sculpture in the Context of American Democracy,” on which he worked from 1968 to 1978, and which he later revisited in 1993.

“Public sculpture is a search for a cultural history which calls for structural unity between the object and its social and spatial setting,” he wrote in the manifesto. “It should be open, available, useful and common.”

Armajani’s retrospective in Minneapolis featured more than 100 works including many pieces from private and public collections in Europe and elsewhere. Some had never before been exhibited in the United States.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/brid4793847.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Siah Armajani, Irene Hixon Whitney Bridge, (1988) Photo by Barbara Economon, courtesy Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”center” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Spanning six decades of the artist’s studio practice, the exhibition brought together models from his Dictionary for Building series (1974-1975) — nearly 150 small-scale maquettes representing the architectural elements of a house that have been combined into different permutations — as well as Fallujah (2004-2005), a monumental antiwar sculpture created in response to the US invasion and occupation of Iraq.

The exhibition also included collages and other works on paper, which the artist made in the late 1950s while in Tehran, and more recent sculptures and models from his Tombs series (1972-2016) and Seven Rooms of Hospitality series (2016-ongoing).

“For six decades, Armajani has been reinventing himself and this by itself is not an easy task,” said Ziba Ardalan, the Iranian-born founder and director of Parasol Unit for Contemporary Art in London, told Kayhan Life in an interview before the artist’s passing. “During this time, he has brought a whole new language to art practice, a language which has endured through time and has inspired other artists.”

“At the end of the day,” added Dr. Ardalan, “the reason an artist is important is purely due to his vision, intelligence, and his/her ability to create works that communicate with and transform our soul.”

Though he never returned to Iran after 1960, Armajani created a sanctuary for himself in Minneapolis in the home he shared with his wife, Barbara.

“I have a small book room with books on Persian miniatures and architecture,” he told The New York Times, “and from time to time I look at them. It’s sentimental, actually. But Persian poetry has tempered and conditioned my general feelings about everything. So, I look at the universe poetically.”

“There is a core to the concept of art, and the longer you live, the more you realize that those foundations are not negotiable,” he said.