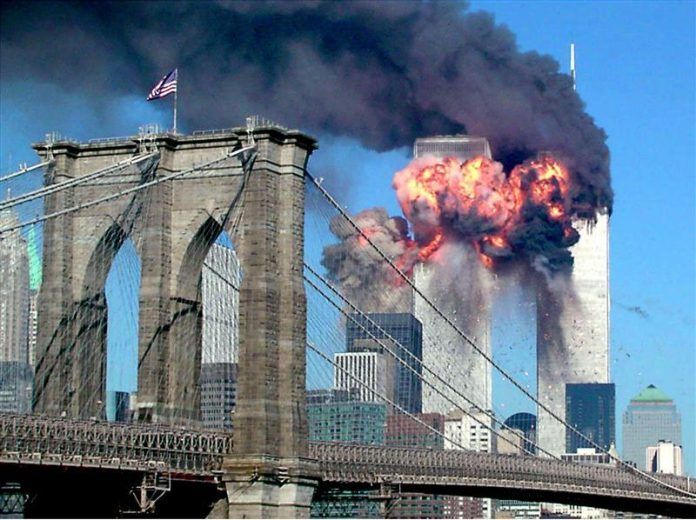

America was under attack. It came not long after George W. Bush had formed his new administration with highly influential neoconservatives and assertive realists at the Pentagon and State Department, as well as in the White House itself. All were determined to see the vision of a “new American century” fulfilled – a neoliberal free-market world rooted in US experience and guided by its post-cold war progress as the world’s sole economic and military superpower.

At the time, commentators compared the attack to Pearl Harbor, but the effect of 9/11 was much greater. Pearl Harbor had been an attack by the naval forces of a state already in great tension with the United States. It was against a military base in the pre-television age and away from the continental United States. The 9/11 attack was a much greater shock, and if war with Japan was a consequence of Pearl Harbor, then there would be war after 9/11 even if the perpetrators and those behind them were scarcely known to the American public.

The vision of the new American century had to be secured and force of arms was the way to do it, initially against al-Qaida and the Taliban in Afghanistan.

A few people argued against war at the time, seeing it as a trap to suck the US into an Afghanistan occupation instead of treating 9/11 as an act of appalling mass criminality, but their voices did not count.

The first “war on terror” – against al-Qaida and the Taliban – started within a month, lasted barely two months and seemed an immediate success. It was followed by Bush’s State of the Union address in January 2002 declaring an extended war against what Bush referred to as an “axis of evil” of rogue states intent on supporting terror and developing weapons of mass destruction.

Iraq was the priority, with Iran and North Korea in the frame. The Iraq War started in March 2003 and was apparently over by May 1, when Bush gave his “mission accomplished” speech from the flight deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln.

That was the high point of the entire US-led “war on terror”. Afghanistan was the first disaster, with the Taliban moving back into rural areas within two to three years and going on to fight the US and its allies for 20 years before taking back control last month.

In Iraq, even though the insurgents appeared defeated by 2009 and the US could withdraw its forces two years later, Islamic State (IS) rose phoenix-like from the ashes. That led to the third conflict, the intense 2014-18 air war across northern Iraq and Syria, fought by the US, the UK, France, and others, killing tens of thousands of IS supporters and several thousand civilians.

Even after the collapse of its caliphate in Iraq and Syria, IS arose once again like the proverbial phoenix, spreading its influence as far afield as the Saharan Sahel, Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bangladesh, southern Thailand, the Philippines, back in Iraq and Syria once more and even Afghanistan. The spread across the Sahel was aided by the collapse of security in Libya, the 2011 NATO-led intervention being the fourth of the west’s failed wars in barely 20 years.

In the face of these bitter failures, we have two linked questions: was 9/11 the beginning of decades of a new world disorder? And where do we go from here?

It is natural to see the single event of 9/11 as turning traditional military postures on their heads, but that is misleading. There were already changes afoot, as two very different events in February 1993, eight years before the attacks, had shown all too well.

First, incoming US president, Bill Clinton, had appointed James Woolsey as the new director of the CIA. Asked at his Senate confirmation hearing how he would characterize the end of the cold war, he replied that the US had slain the dragon (the Soviet Union) but now faced a jungle full of poisonous snakes.

During the 1990s, and very much in line with Woolsey’s phrase, the US military moved from a cold war posture to preparing for small wars in far-off places. There was more emphasis on long-range air strike systems, amphibious forces, carrier battle groups and special forces. By the time Bush was elected in November 2000, the US was far more prepared to tame the jungle.

Second, the US military and most analysts around the world missed the significance of a new phenomenon, the rapidly improving ability of the weak to take up arms against the strong. Yet the signs were already there. On February 26, 1993, not long after Woolsey had talked of a jungle full of snakes, an Islamist paramilitary group attempted to destroy the World Trade Center with a massive truck bomb placed in the underground car park of the North Tower. The plan was to collapse it over the adjoining Vista Hotel and the South Tower, destroying the entire complex and killing upwards of 30,000 people.

The attack failed – though six people died – and the significance of the attack was largely missed even though there were many other indicators of weakness in the 1990s. In December 1994, an Algerian paramilitary group tried to crash an Airbus passenger jet on Paris, an attack foiled by French special forces during a refueling stop at Marseilles. A month later a bombing by the LTTE of the Central Bank in Colombo, Sri Lanka devastated much of the central business district of Colombo, killing over 80 and injuring more than 1,400 people.

A decade before the first World Trade Center attacks, 241 Marines had been killed in a single bombing in Beirut (another 58 French paratroopers were killed by a second bomb in their barrack) and between 1993 and 2001 there were attacks in the Middle East and East Africa including the Khobar Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia, an attack on the USS Cole in Aden Harbour and the bombing of US diplomatic missions in Tanzania and Kenya.

The 9/11 attacks did not change the world. They were further steps along a well-signed path leading to two decades of conflict, four failed wars, and no clear end in sight.

That long path, though, has from the start had within it one fundamental flaw. If we are to make sense of wider global trends in insecurity, we have to recognize that in all the analysis around the 9/11 anniversary there lies the belief that the main security concern must be with an extreme version of Islam. It may seem a reasonable mistake, given the impact of the wars, but it still misses the point. The war on terror is better seen as one part of a global trend that goes well beyond a single religious tradition – a slow but steady move towards revolts from the margins.

In writing my book, Losing Control, in the late 1990s – a couple of years before 9/11 – I put it this way:

What should be expected is that new social movements will develop that are essentially anti-elite in nature and will draw their support from people, especially men, on the margins. In different contexts and circumstances, they may have their roots in political ideologies, religious beliefs, ethnic, nationalist or cultural identities, or a complex combination of several of these.

They may be focused on individuals or groups, but the most common feature is an opposition to existing centres of power … What can be said is that, on present trends, anti-elite action will be a core feature of the next 30 years – not so much a clash of civilizations, more an age of insurgencies.

This stemmed from the view that the primary factors in global insecurity were a combination of increasing socioeconomic divisions and environmental limits to growth coupled with a security strategy rooted in preserving the status quo. Woolsey’s “jungle full of snakes” could be seen as a consequence of this, but there would be military responses available to keep the lid on problems – “liddism” in short.

More than two decades down the road, socioeconomic divisions have worsened, the concentration of wealth has reached levels best described as obscene and has even increased dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic, itself leading to food shortages and increased poverty.

Meanwhile climate change is now with us, is accelerating towards climate breakdown with, once again, the greatest impact on marginalised societies. It therefore makes sense to see 9/11 primarily as an early and grievous manifestation of the weak taking up arms against the strong, and that military response in the current global security environment woefully misses the point.

At the very least there is an urgent need to rethink what we mean by security, and time is getting short to do that.