Farzaneh Kaboli is an Iranian ballet dancer, choreographer, stage and film actress. She was one of the country’s most famous ballerinas before the Revolution.

The Islamic Republic imposed a ban on dancing after the 1979 revolution. Despite severe restrictions, Ms. Kaboli continued to pursue her artistic activities and worked as a choreographer, teaching ‘form and rhythmic movements,’ which replaced ‘dance’ under the Islamic Republic.

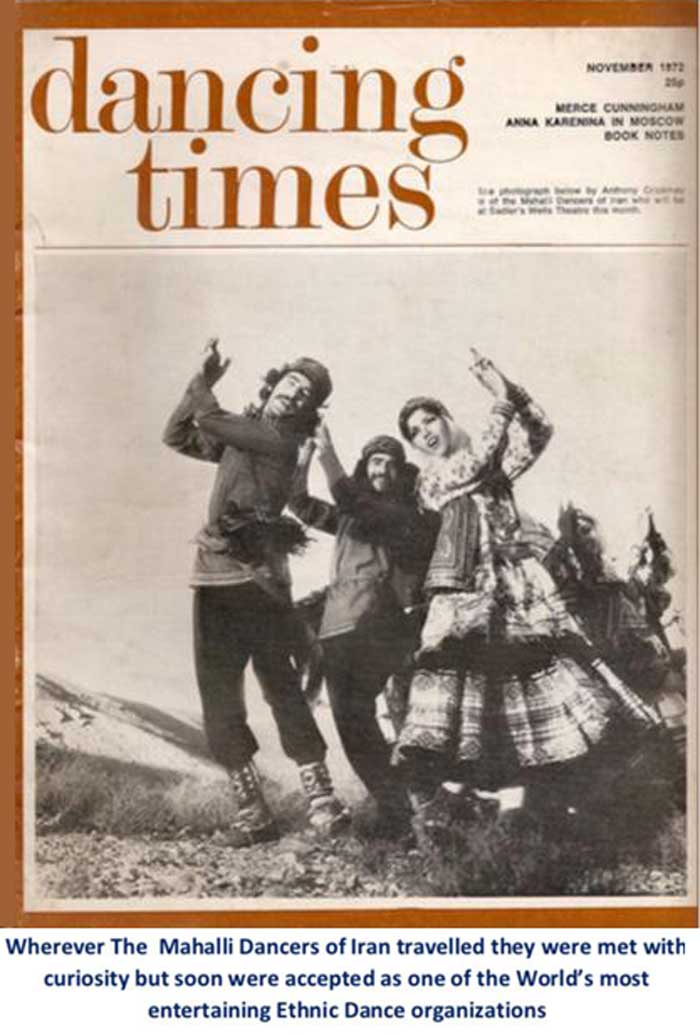

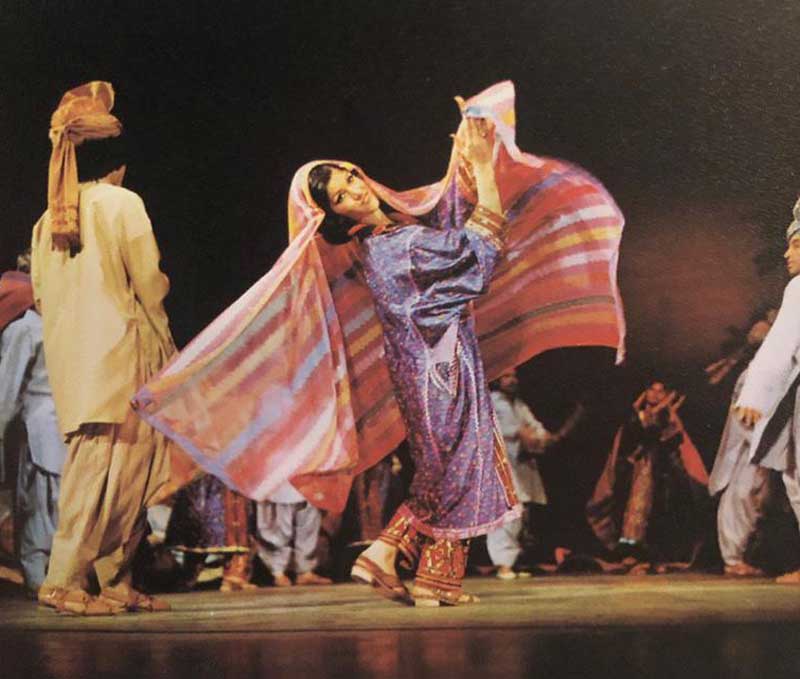

Kaboli was born into a musical family and began dancing at an early age. She was a champion high jumper for several years before enrolling in the Iranian National and Folklore Dance Academy, at her father’s encouragement. She studied dance under the British choreographer Robert de Warren, and received acting training from her husband, Hadi Marzban, an Iranian theatre director.

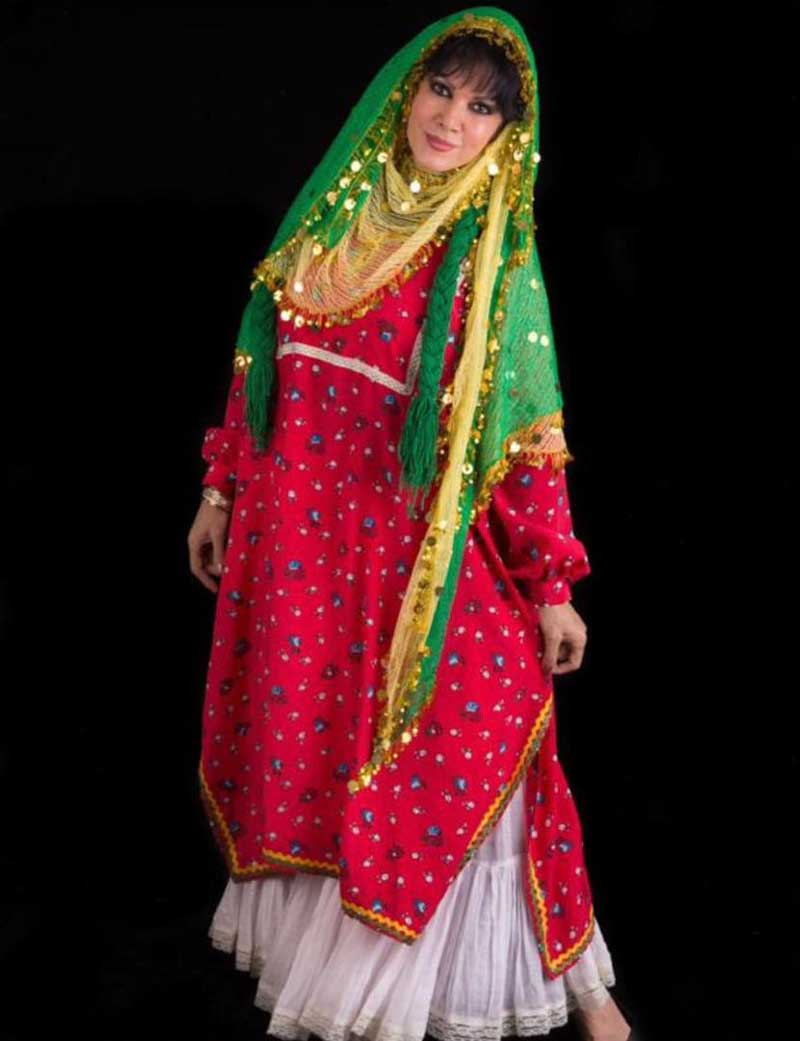

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/farzaneh-kaboli_2.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Farzaneh Kaboli. KAYHAN LONDON./” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Kaboli joined Kayhan Life for a wide-ranging conversation on the occasion of International Dance Day (March 29).

Ms. Kaboli, why have you stayed in Iran despite being arrested and imprisoned twice?

I love this country. I love my work and my students who live here. My work differs from all other jobs because it attracts audiences no matter where I go in the world. I can stage a performance anywhere with little effort. I can do the same here, except that I can perform only for female audiences.

I love it here because I have students who started with me when they were three years old and now are 25. I have watched them grow, and that is important to me. That is the fruit of my efforts. I have 29-year-old students who still study with me. I have watched them grow, mature, and succeed, which is precious. So I need to stay here.

My husband, mother, and I are all American citizens. I lived in the U.S., but couldn’t stay there, and returned to Iran. I am very sentimental and am thrilled to be living in Iran.

When did you become interested in dance?

I fell in love with dance at an early age, even before I could walk. I responded to musical rhythms by jumping up and down. My father was an accomplished santoor player, and my mother played the accordion. My maternal uncle Mr. Garmsiri was an acting instructor, and his brother was a singer who performed on the radio.

I was born into an artistic family, so one might say it was in my genes. While I was in high school, they would ask me to organize programs to celebrate important occasions, including Mother’s Day and the birthday of the Shah [Mohammad Reza Pahlavi]. I was also a champion high jumper.

I cut my hair short and performed as a male dance partner with a girl who was a friend of mine. I choreographed the dances and represented our high school in several competitions held at Tehran’s Farhang Hall.

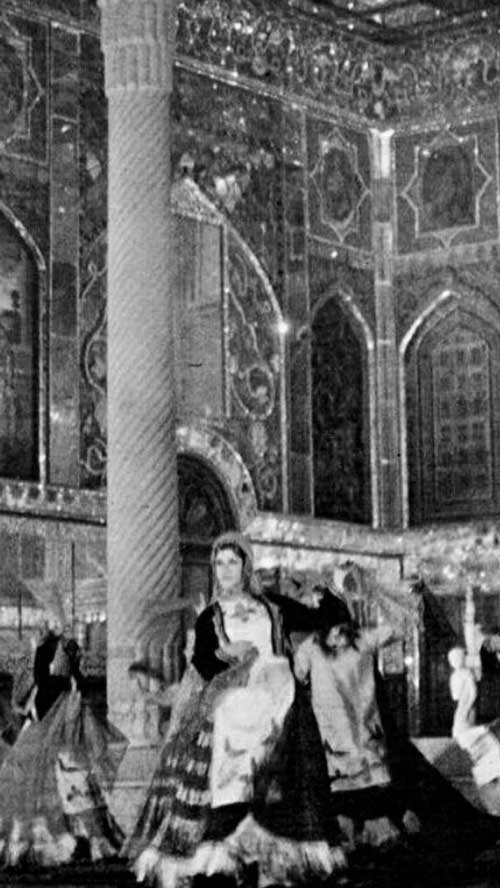

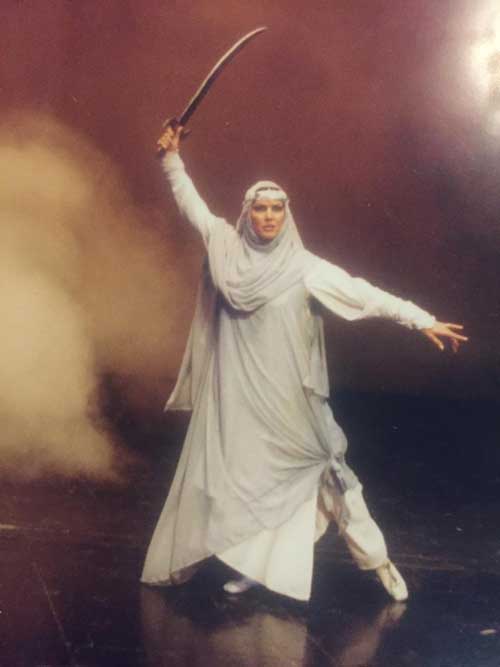

You were a member of a five-person team of dancers who performed for world leaders at the Persepolis celebrations marking 2,500 years of Persian Empire.

They asked five of us to choreograph dance routines for pieces of music assigned to each of us. However, I was the only person who choreographed a dance routine. I was also selected as part of a dance company to perform at the Persepolis celebrations. Dancers rotated and performed several solo routines for world leaders. I am proud of that performance.

How have you and other dancers continued to work after the Revolution?

They moved us to the Performing Arts department, since we worked for the Ministry of Culture, and we were given meaningless jobs. Subsequently, they tested dancers, and I was given the only available position for an actor. I was thrilled to get that job, and that is how I started in theater.

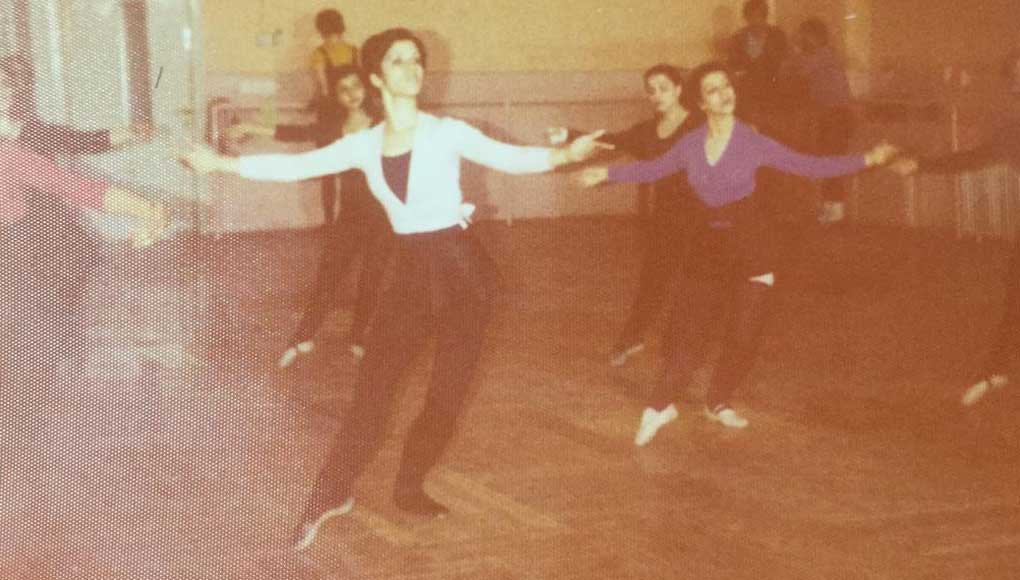

I held private dance classes and never worked with a group. I have group dance classes now and work with children in a large studio. In the years that I worked from my home, I would gather the students, sometimes up to 35 of them, in my house at the end of each year, making a video recording of our achievements. I designed their costumes, put on their makeup, and choreographed their solo dances.

In the early 1990s, a magazine interviewed me four or five days after a performance. A few days before the interview, the magazine had informed its readers that I would be at their offices. I received calls from across the country from people who wanted to know if something had happened to me and whether I was fine. I asked one caller why they were concerned.

They had seen one of my films, the caller said. I thought they were referring to one of the movies I appeared in. However, I discovered that one of my irresponsible students had shared the video that I had made of children’s performances at my house with many people. I spent a month and a half in Tehran’s Evin Prison after the publication of the footage.

You were also summoned to court after Salar Aghili’s concert in August 2019.

Salar Aghili planned to perform 10 pieces of music. Given the Islamic Republic’s red lines, I only worked with the serious pieces and avoided the upbeat songs. I knew that we needed to restrict and limit movements during the performance to prevent any problems. So I choreographed only dances for five pieces performed by Salar.

Representatives from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance’s council on performing arts saw the work twice and photographed the costumes. The costumes were baggy and designed in line with strict hijab guidelines, making them suitable for all performing events. The costumes included headscarves decorated with sparkling sequins.

We scheduled two performances on a single day at Tehran’s Milad Hall. Salar Aghili’s wife called me at around five o’clock in the afternoon, saying that they had canceled the first performance scheduled for seven O’clock. She said the manager of the Milad Hall had told her that the event could go ahead ‘only over his dead body because there was a woman dancer in the concert.’

That was not very pleasant. I had to let all dancers, who were already en route to the venue, turn around and return home. She called me back at around 6 p.m., saying that we should go ahead with the 9 p.m. performance if we missed the one scheduled for 7 p.m. I contacted everyone again and asked them to come to Milad Hall. They made it in time for both the 7 and 9 p.m. performances.

It was an outstanding performance, which amazed the audience. I was invited to sit in the front row. Salar introduced me when the dancers came out to perform, saying I had managed the event. I got up, turned to the audience, and acknowledged their applause.

Footage of the performance was published shortly afterward. I received a call from the Tehran prosecutor’s office the next day, summoning me to be interviewed by a judge. My husband accompanied me the following day to the prosecutor’s office, but I sat alone with the judge. After he signed a few documents, the judge turned to me and said that I had danced on stage the previous day. I said I knew the Islamic Republic’s red lines, and I had not danced.

As the video clip of the performance showed, I noted that I was not on stage but sitting in the front row with the audience. The footage showed that I got up from my seat to thank the audience. The judge asked if I had not already performed for female audiences, to which I said yes. He then asked why then I had staged a performance for a mixed-sex audience. I told him that was what I did, and that I did not see a problem staging an event since I had a permit.

He gave me a piece of paper to sign. I refused to sign the document, saying I did not know the content. The judge said he had written everything I had just said. I eventually signed it only after reading it and made sure it was the correct account of what I had said.

He asked me if I had scheduled another performance. I said we had planned two other events at Hotel Espinas in Tehran. He asked if we were going ahead with the events. I wondered why I should do it in such a climate, particularly since I had endured great hardship during the month and a half that I spent in Evin Prison.