“Down and Across,” published by Penguin Random House, is the debut novel by Iranian-American Arvin Ahmadi: a coming-of-age story of grit and self-discovery that follows Scott Ferdowsi, a high-school student with a propensity to quit projects.

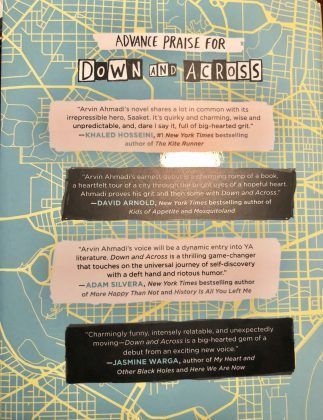

“Down And Across” has received praise and positive reviews from notable authors such as Khaled Hosseini (“The Kite Runner”), David Arnold (“Kids of Appetite and Mosquitoland”) and Eric Smith (“The Girl and the Grove”).

Ahamdi’s foray into the young adult category has been a success, with his novel being listed in the “Most Anticipated Books of 2018” by Bustle, BN Teen Blog, BookRiot, Bookish, Hypable and Brightly.

Kayhan Life had a chance to speak to Arvin Ahmadi shortly after the release date of his book.

What is “Down and Across” about and what is the significance of the title?

“Down And Across” is about 16-year-old Saaket “Scott” Ferdowsi, a chronic underachiever whose Iranian parents want him to get serious and pursue a career like medicine or engineering. When his parents leave the country to take care of a sick relative, Scott ditches his summer internship and runs away to Washington, D.C., hoping to meet a famous professor who specializes in grit, or the psychology of success.

Along the way, Scott meets a cast of interesting characters, finds himself in sticky situations, and opens his eyes to who he is and who he wants to be.

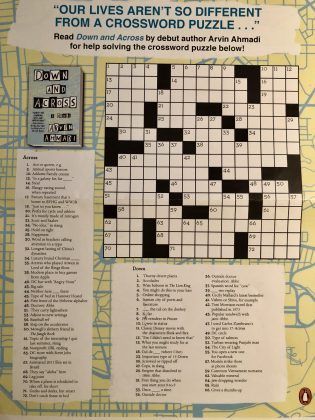

The title came organically. In one of the early chapters, Scott is on the bus to DC when he meets a girl, Fiora, who writes crossword puzzles. I wasn’t sure if Fiora or the crossword puzzles would return, but they did in a later chapter in a really interesting way—and that’s when I decided the title.

How did you get the idea to write this book?

I didn’t mean to write this book. I studied computer science and political science in college. My senior year, I watched a TED talk by Angela Duckworth, the MacArthur Grant “genius,” where she said the number one indicator of success isn’t your IQ or socioeconomic status, but grit—the ability to persist and overcome failure.

It got me thinking about failure and grit. Can a person who constantly fails, who has a track record of giving up, be gritty? I’d switched my college major seven times and still wasn’t sure about my path. I didn’t have a 10-year plan.

Two personal failures then came to mind. When I was 10 years old, I started writing a novel and emailed the first three chapters to literary agents. All of them rejected or ghosted me, so I gave up. And when I was 16 years old, I tried running away from home. I can’t even remember what I was arguing about with my parents that time. But I wound up in Washington, DC, and hung around until it got dark. At that point, it occurred to me that I didn’t have much money or a place to sleep, so I called my parents from a payphone and they picked me up.

I thought back to those failures and decided I wanted to pick up where I left off. I started writing the story of a teenage boy who runs away to get gritty, and I told myself I had to finish it. And I did.

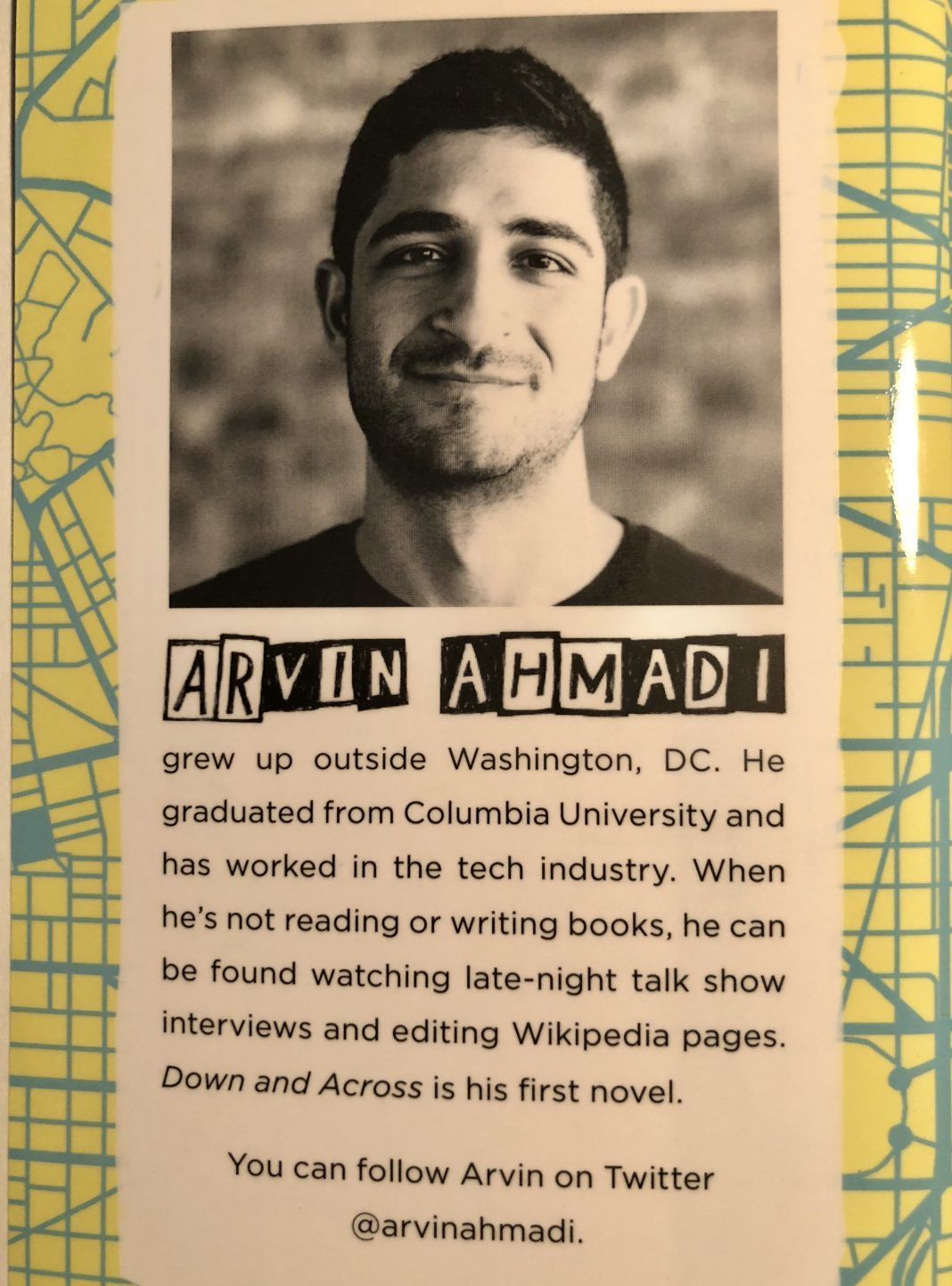

There seems to be a lot of similarities in this book and your life. Is “Down And Across” a memoir, and are the characters based on people you know? What is your family background, where were you born, raised and educated?

My parents emigrated from Iran in the late 1970s. I was born in the Washington, DC area and grew up in Fairfax County, Virginia. I attended a magnet high school in Alexandria, Virginia, and spent four years in New York City at Columbia University.

I think many, if not most, debut novels are autobiographical. I tried to distance myself from my protagonist at first by changing his ethnicity, but eventually I accepted that this book was inspired by my experiences and decided to write an authentically Iranian character.

Pretty much all of my characters reflect people in my own life. It’s not just my friends and family; a lot of the characters I write are inspired by strangers or people I’ve briefly crossed paths with. I actually prefer that, because then I don’t know the person’s entire story; it leaves more to the imagination.

What was the hardest scene or chapter to write and how long did it take you to write the book?

I don’t think I had a hardest scene or chapter in “Down and Across,” because the story was so personal. I will say, the revision process was a challenge because I drafted the novel in a very stream-of-consciousness way. When I went back to revise, I realized I needed to tinker a lot of pieces to inject tension and conflict. I had to keep the story moving.

I spent a year writing the first draft and another 14 months revising.

What is next and will there be a sequel to “Down and Across”?

Do you want your next books to stand on their own, or are you trying to build a body of work with connections between each book?

Nope! There won’t be a sequel.

I certainly don’t want to get typecast or pigeonholed as a writer. I like writing about different subjects. But I do think there are certain themes I gravitate towards—the pressure to succeed, cultural diversity, and the idea that people are very different than how they appear on the surface. And nerdy humor. There has to be a touch of lightheartedness in everything I write.

I’m working on a novel that’s actually very different from “Down And Across.” It’s a near-futuristic story set at a boarding school in Palo Alto, California, about a girl who enters a virtual reality contest with the secret goal of meeting an elusive billionaire who may or may not have killed her father.

Kayhan Life has a large number of followers who are Iranian or from Iranian descent. What is your relationship with Iran and do you have a message for our readers?

I visited Iran when I was 15 years old and absolutely loved it. Iranians are some of the warmest people you’ll ever meet. They welcome you into their homes; feed you until you’re just about ready to roll over… it’s a culture of boundless energy and love. And of course, Iran itself is a beautiful country. You see palaces and bridges and bazaars that are thousands of years old. The experience is even more awe-inspiring when you think about it in the context of Iranian art, literature, and science. It’s a shame more people don’t get to travel to Iran, because I think they’d be pleasantly surprised by how much Iran has given to the world and how much the Iranian people are willing to give.

Honestly, I don’t write with a particular message at the front of my mind. I do feel hopeful about the future of Iranians, though, especially young Iranian Americans such as myself. Growing up, I wanted to be completely “American” and shed my Iranian roots. But now that I’m an adult, I find myself embracing my background more and more.