By Tim Cornwell

Steps away from the glistening Grand Canal is a corner of Venice that has turned Iranian this summer.

In the 17th-century palace that is the city’s music school, where grand courtyards with Roman busts echo with the melodies of practicing pianists and cellists, the London-based Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art is staging a milestone show of nine Iranian artists, ranging from international veterans to new names.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/TSIY-INSTALL-28.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

A couple of minutes away, the official Iranian national pavilion is showing three artists with brand-new commissions, also spanning generations. They include a giant papier-mâché banqueting table by Tehran’s Reza Lavassani, laden with poetic symbolism, featuring everything from a giant chandelier to nightingales and delicate flowers, and missing only human guests. Getting the work to Venice in five crates has surely been half the battle.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IMG_6255-e1557496079493.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IMG_6254.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IMG_6253.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”‘life’, Reza Lavassani. Photo by: Tim Cornwell.” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”center” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Over 600,000 people visited the Venice Biennale in 2017. There’s every indication the numbers will be even higher this year. The opening week was a gathering of everyone from Russian collectors on super-yachts to the celebrated artist El Anatsui, showing in Ghana’s first-ever pavilion.

“There are two ways to promote art,” says Mohammed Afkhami, a prominent collector of Iranian contemporary art, and one of the supporters of the Parasol Unit show, titled “The Spark is You.”

“One is to try to move shows into a city with one or two museums, but it only addresses that audience. Then there’s another way, of bringing it to Venice for the opening of the Biennale.”

There is nothing parochial about the Iranian work on show. It fits entirely with the Biennale setting, with little to signal any national origin.

In the grandiose spaces of the Conservatorio di Musica Benedetto Marcello, a highlight of “The Spark Is You” is a deliciously witty 14-minute video by Mitra Farahani. It features tour guides in front of Caravaggio’s gruesome classic, David and Goliath, in the Borghese Gallery in Rome, wryly observing their varied reflections on Goliath’s decapitated head for groups of multi-national visitors. “Take my head, but stop doing my head in,” Farahani’s voiceover says.

Nearby is the last work by the late Farideh Lashai, reanimating another masterpiece, Goya’s “The Disasters of War,” to the music of Chopin.

There is a 2008 installation by Siah Armajani, an extraordinary cell-like vision of the American writer Edgar Allan Poe’s Study, with a desk, an empty jacket, and a tomb. Armajani emigrated to the US as a student in 1960.

The end wall of the same palatial room is a work by an Iranian artist who is 40 years younger. Five meters square, Nazgol Asarinia’s piece “Membrane” is a printed 3-D scan of the traces of a demolished house in Tehran, the shadow outline left behind on the wall of an adjoining building. Like a photographic negative, it shows the ghost of stairs, kitchen, bathroom, of lives lived. The artist’s work captures the rapidly changing architecture of Tehran, with old structures replaced by gaudy new homes.

One of the joys of the Venice Biennale is to see contemporary art curated in extraordinary classical settings. Both Navid Nuur’s works “The Tuners,” giant panels of painted doodles, and Sahan Hesamiyan’s “Forough,” shining geometric sculptures that look like a cross between tulips and an Apollo capsule, are sited in high-pillared courtyards full of Venetian statuary. For months to come, visitors will enjoy them with the soundtrack of opera singers and musicians practicing their crescendos.

The show includes the celebrated artist YZ Kami, with three new paintings; he is represented by the Gagosian Gallery, an international powerhouse of the contemporary world.

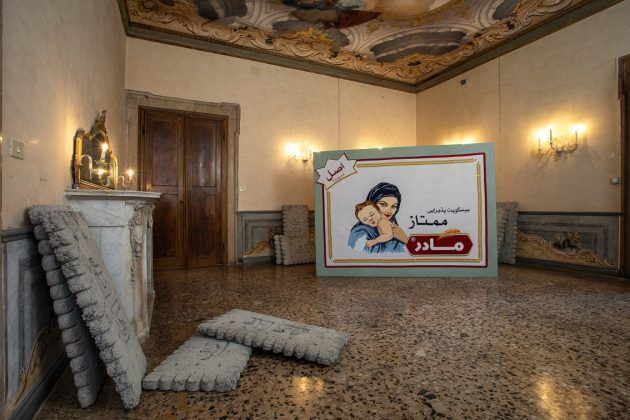

By contrast, Tehran-based Morteza Ahmadvand has no international representation yet. His work “Becoming,” a piece where religions symbolically blend into a huge black sphere, has severe lines beautifully offset by the painted ceiling above. But one of the show’s most intriguing pieces, a giant box of “Biskweet-e Madar,” (Mother Biscuits), by Koushna Navabi, with cement biscuits lying around the floor, suffers from the setting, losing impact to the elaborate decoration of the room around it.

Work by Iranian artists has been seeded through the global contemporary art scene for decades now. The Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art, a non-profit art gallery founded in London 15 years ago by Ziba Ardalan, long focussed on art from all over the world rather than any particular region.

But at a time of escalating tensions, she said, the emphasis is “to show and bring to Venice that aspect of culture and humanity in Iranian people and Iranian artists. The whole show is about tolerance and openness and dialogue, and to encourage people to think of ‘Iranian’ in a different way.”

“The Spark is You,” with a counterpart exhibition in London, has taken Ardalan back to her own roots.

Hosseini is one of nine artists on show in Heartbreak. Another highlight is undoubtedly artist Lana Čmajčanin’s commission, a work that consists of around 100 maps, overlaid on each other on a back-lit map table; they represent the different lines drawn on the sand of the region over centuries. In a separate space in the same building Tamara Chalabi has also co-curated the official Iraq pavilion, featuring the powerful painting of Serwan Baran.

The official Iranian pavilion showcases new work by three artists, in a former water-side warehouse now used as an exhibition venue. Titled “Of Being and Singing,” curated by Ali Bakhtiari, the national show is informed by the “mundus imaginalis,” from a phrase first used by the 12th-century Persian philosopher known as Sohravardi, for a boundary world.

Reza Lavassani, a painter, sculptor and stage designer, has been working on “Life,” the giant banqueting table, for at least three years. Merely getting it to Venice, with sanctions making shipping and insurance a nightmarish challenge, seems a stunning achievement. The piece seeks to convey the different stages of life; the audience is left to wrestle with his meaning, and decipher allusions wrapped in poetry and symbolism. Horses on the table represent dynamism and speed.

A papier mache last supper of inedible fruit and flowers, from grey newspaper pulp, it is said to speak of recycling and redesign, the passage of life from the grand events, the giant chandelier, to tiny morsels, the dots of words, scattered across the table.

The most powerful part of the piece is an empty armchair, with a table beside it. It speaks loudly of the empty nesting place of some cherished relative; the “absence of presence.”

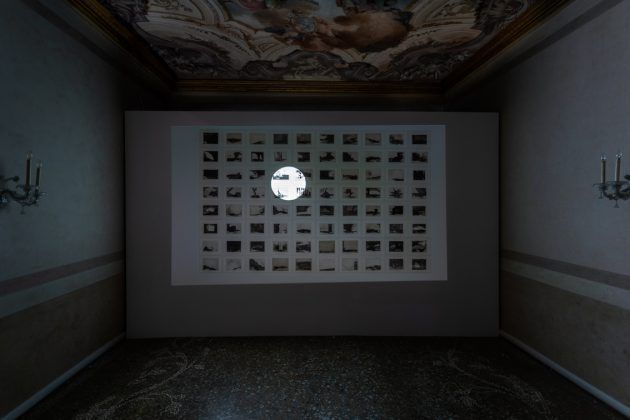

The plain rooms of the venue create much more of a traditional white cube space, modest in scale. The displays includes a complex installation by the youngest artist, Ali Meer Azimi, inspired by a famous scene from film-maker Abbas Kiarostami’s 1973 classic “The Traveler.”

More accessible are Samira Alikhanzadeh’s surreal figures, suggesting young women outlined by coat hangers, silhouettes and shoes. Immediately compelling, the works use found family portraits from the 1950s; in the background are the lines of imaginary letters from a girl to her fiancé after watching the film of Anna Karenina, starring Greta Garbo, and becoming obsessed by the dresses Garbo wore.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IMG_6251-1-e1557496584161.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/IMG_6252-1-e1557496520580.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=” ‘The Rigid Phantom of Memory’. Artist: Samira Alikhanzadeh. Photo by: Tim Cornwell. ” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”center” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

The Iranian work is not limited to the two big shows. Bizhan Bassiri, the 2017 Iranian pavilion artist, is showing a 10-meter-tall bronze colossus in the courtyard of one Venetian art collection. Veteran Middle Eastern art curator Janet Rady has sited two sculptures by Iran’s Masoud Akhavanjam in a prominent waterside garden (where other artists include the remarkable Lebanese architect and sculptor Nadim Karam).

“Contemporary Iranian art has been going from strength to strength in the last few years,” said Rady, “and the number and quality of works being shown at this year’s Biennale is a testament to the seriousness of Iranian culture and artistic production both within the country and on the international art stage.”

©THE SPARK IS YOU: Parasol unit in Venice

Installation view at Conservatorio di Musica Benedetto Marcello, Venice, 2019.

Courtesy the artist and Parasol unit.

Photography by Francesco Allegretto