Persian tahdig… the most coveted treat at a Persian meal… at times referred to as the jewel of Persian cooking… or the holy grail of Persian cooking… or the pièce de resistance of the Persian cook… It is described as the delicious, buttery, golden, crunchy, round layer from the very bottom of the rice pot. In reality, however, tahdig is much more than that. This short essay is a broad look at “all things tahdig” including some innovative practices that Persian cooks have introduced over the years into the process of making tahdig.

Literally translated, the Persian word tahdig (in Persian “ته دیگ”) means “bottom of the pot.” The classic process involves the long-grain rice going through the stages of being soaked in salted tap water for several hours up to a day, parcooked in salted boiling water for several minutes, drained, rinsed with cold water, and then slowly steamed in a pot with melted butter on the bottom over low heat for an hour or two, while covered tightly, during which the tahdig is formed at the bottom of the pot.

Actually, however, tahdig has become much more than the crunchy layer of rice from the bottom of the pot. In addition to it being eaten by itself, it is consumed in many other ways, forms, and shapes including being used as a vessel to eat other Persian delights. Moreover, in addition to preparing it with just plain white rice alone, its preparation includes other ingredients including spices, dairy, breads, vegetables, meat, poultry, seafood, and pasta. What follows is a broad look at “all things tahdig” demonstrating a wide range of imaginative ways Persian cooks prepare tahdig-centric dishes.

The Solo Crunchiness

First and foremost, tahdig is served as a solo accompaniment along with the Persian rice dish that created it. Traditionally, pieces of tahdig are scraped off the bottom of the pot and served either on the same platter as the accompanying rice dish (See Figure 1) or on a separate smaller plate (See Figure 2). If served on a separate plate, it is passed around the table separately from the rice platter. With the proliferation of non-stick cooking vessels, the whole unbroken layer of tahdig can be removed from the bottom of the pot and served. (See Figure 3).

A Means for Soaking Liquid Goodness

Persian rice is often served along with one of the numerous types of Persian exquisite slow-cooked stews which are called “Khoresh” (in Persian “خورش”). A common practice among Persian food lovers is to pour some of the stew over their pieces of tahdig to soak some of the liquid goodness of the stew. In fact, in Persian restaurants, if one simply orders tahdig, it often comes with a small portion of one the more popular Persian khoreshes; typically, either the yellow split pea khoresh – khoresh-é-gheimeh – or the green herb khoresh – khoresh-é-sabzi. (See Figure 4) to pour over the crunchy rice.

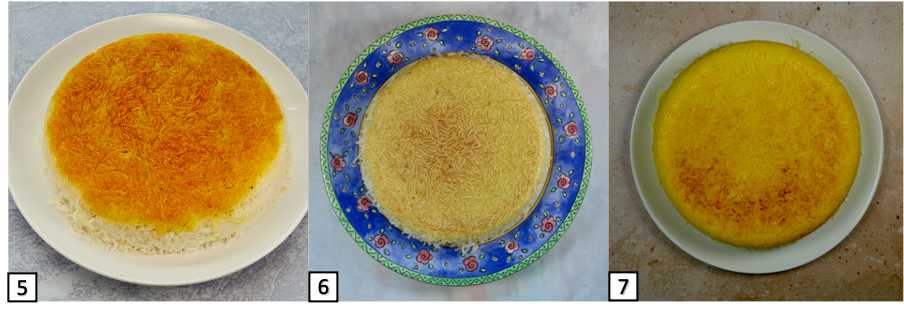

Flavored Tahdig

During the preparation of the famous Persian steamed rice, called “chelow,” during which tahdig is formed, it is not uncommon for some cooks to add a small amount of flavorings to the oil or butter that goes on the bottom of the pot. The most common ingredients used by Persian cooks to enable such flavorings are steeped liquid saffron, yogurt, and/or egg yolk. Adding a few tablespoons of steeped liquid saffron enhances both the color and the aroma of the tahdig (See Figure 5) while adding a few tablespoons of yogurt (See Figure 6) and/or an egg yolk (See Figure 7) will both change the texture and the flavor of the resulting tahdig. Addition of yogurt reduces the amount of oil needed and introduces a good amount of tanginess to the tahdig. Addition of egg yolk results in a softer tahdig with a slight omelet flavor.

A Place and a Technique for Creating Other Crunchy Delights

Over the years, Persian cooks have expanded the technique of creating a crunchy layer of rice at the bottom of the pot to other ingredients besides rice by carefully incorporating vegetables, bread, meat, poultry, and seafood into the process. In addition to creation of an expanded set of crunchy delights, the modified methods provide an opportunity for other ingredients to be cooked at the same time and within the same vessel as the rice. The idea behind these modified techniques is first adding a bit of liquid oil or melted solid oil on the bottom of the pot and then fully or partially covering the bottom of the pot with slices or pieces of other ingredients before parboiled rice is piled back into the vessel and steamed for an hour or two over low heat.

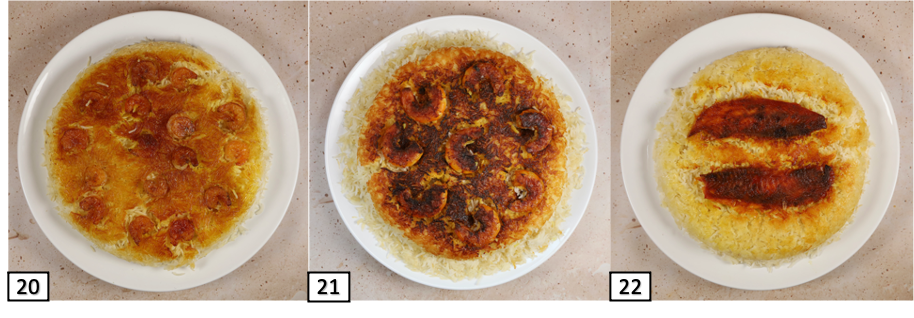

Incorporating slices of potato into the tahdig (See Figures 8-10) is the most popular of such modifications. Incorporating various flat breads (in particular, Persian Lavash) into the tahdig making process is the next most popular (See Figures 11-13). As it is evident from Figures 12 and 13, incorporating flat bread into tahdig making process also provides a canvas for culinary artistry!

Similar techniques as those used for potato tahdig and bread tahdig can be used to incorporate various vegetables or pieces of meat, poultry, and seafood – Examples are shown in Figures 14-22. Careful control of level of heat, amount and type of oil, moisture, and duration of cooking are essential to control the level of crunchiness desired anywhere from partial crunchiness to charred, based on individual preferences (see, for example, pairs of Figures 14-15, 17-18, and 20-21).

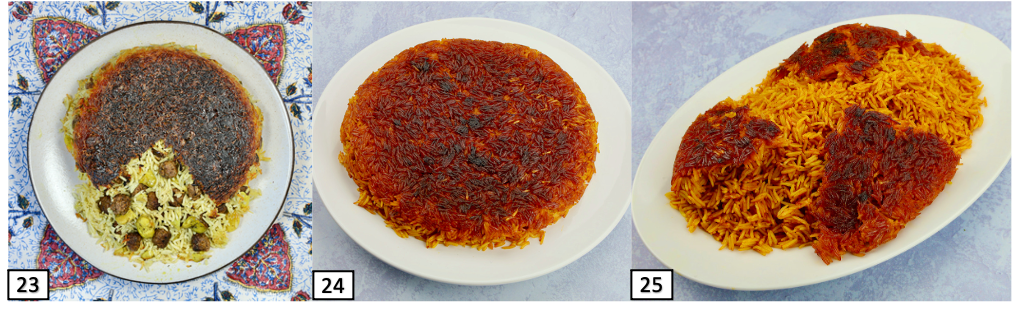

Tahdig Resulting from Various Persian Flavored Rice Dishes – Polow Tahdigs

Our discussion so far has been about tahdigs resulting from Persian cooking techniques of plain rice parboiled and then steamed over a very low heat. The resulting plain rice, called “chelow” (in Persian: چلو), is then typically served along with a Persian stew or other types of meat dishes including famous Persian grilled kabābs. There is, however, another important and popular category of Persian rice dishes, called “polow” (in Persian: پلو) where rice itself (either during it being parboiled or shortly after the parboiled rice has been drained) is augmented with various flavorings and ingredients (somewhat similar to Indian Biryani rice dishes) before being put back into the pot, tightly covered and steamed for another hour to two. The tahdigs from these class of rice dishes are as popular and as sought after as the plain rice tahdigs. They have the same flavor and contain the same ingredients that is part of the flavored rice dish. Examples are shown in Figures 23-25. The tahdig in figure 23 is from the bottom of a very famous Persian polow rice dish where fava beans and chopped dill is mixed with the rice at the time of rice being parcooked. Figures 24 and 25 show the tahdig from the bottom of a very simple, but popular, Persian polow rice dish where tomato paste is incorporated into the rice after the rice has been drained before being put back into the pot to steam.

The Ultimate Persian 3D Crunchiness

Another important category of Persian rice dishes that have major tahdig significance are called “Tahchin” (in Persian: ته چین). In this category of rice dishes, large amounts of yogurt, egg yolks, and liquid steeped saffron is mixed with all or most of the parboiled rice after the rice has been drained. The resulting mixture is then carefully arranged (the literal translation of Persian word Tahchin is “arranged on the bottom”), often layered with pre-cooked meat that has been slathered or dipped in yogurt (or other flavorings), starting from the bottom of the pot. Careful steaming, with the pot tightly covered, over low heat for an hour or two, results in one of the Persian cookery’s most prestigious dishes as depicted in Figures 25-26. Carefully filliping the vessel uncovers a 2-4 inch (5-10 centimeters) thick cake-like delight that has crunchy tahdig not only over the top but also on the sides (just like when a cake is covered with frosting). Traditionally, tahchins were prepared for special occasions (cultural and religious celebrations, parties, meals for special guests, or when going out to restaurants). With the proliferation of non-stick vessels, its preparation has somewhat simplified, and hence, become more popular.

Extending Tahdig Making Beyond the Domain of Rice

Persian “mākāroni” (in Persian: ماکارونی) is a popular Persian pasta dish – practically the only popular pasta dish in Persian cookery where medium size dry tube pasta (typically #15, a.k.a. Bucatini) is prepared in the same manner as the Persian plain rice, chelow, is prepared. Tubes of dry pasta are broken into 5-6 centimeter (2-3 inch) pieces, cooked in boiling salted water slightly beyond the al dente stage, drained, mixed with a simple tomato-based red sauce (with or without meat), poured back into the pot after having put some oil on the bottom of the pot, covered tightly, and cooked further for about an hour over very low heat. This results in a layer of delightful crunchy pasta in the bottom of the pot (see Figures 28-29) that is fought over by the dinners in the same manner that they would fight over the rice tahdig.

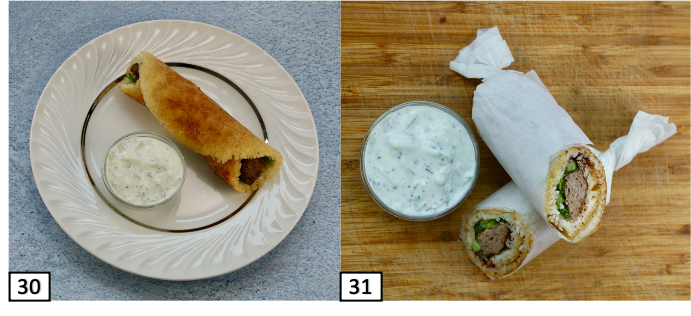

Tahdig Sandwiches

Careful attention to controlling the amount of oil, moisture, and heat, the cooking vessel, and the duration of cooking can result in a crispy layer of tahdig that is not as brittle as normal tahdigs. Such pliable pieces of tahdig can then be used as bread substitute to make a range of sandwich-like dishes. As depicted in Figures 30-31, such pliable pieces of tahdig can be used to create rolls and wraps. They can create delicious taco-looking dishes filled with hot or cold Persian delights as depicted in Figures 32-33. And finally, one can use round pieces of tahdig as sandwich buns to prepare hamburger-like sandwiches as depicted in Figures 34-35.

Not Letting the Last Few Tahdig Crumbs to Go to Waste

Back when there were no nonstick cooking vessels, tahdig had to be scraped out of the bottom of the pot in small or large pieces. This process always created some leftover tahdig crumbs (individual crunchy rice kernels) at the bottom of the pot. Some home cooks, including my maternal grandmother, would throw a fistful of cooked rice onto the bottom of the pot to capture both the tahdig crumbs and the naturally remaining butter from the bottom of the pot. The cooks would then put a few tablespoonsful of the mixture in the palm of one hand, close their fist, and form an oblong-shaped delightful snack approximately 2 centimeters wide and 4 centimeters long. In Persian, the common (slang) name for this scarce creation is “Changāli” [in Persian: چنگالی] (literally meaning something that was formed by closing fingers towards the palm of the hand forming a fist). If there were any “Changāli” formed, they would typically come out of the kitchen to the table after the rest of the meal had already been served. The cook would typically give them to her or his “special people” at the table (as there would only be at most three or four of them) such as the younger members of the family. A double sign of love and caring of the cook – for not letting anything go to waste and for sharing it with the most loved ones at the table. The process is depicted in Figures 33-36 and the resulting delights are shown in Figure 37.

Closing

This brief passage has been a broad, but not exhaustive, look at variations of Persian tahdig and the associated traditional principals and innovative practices that Persian cooks have introduced over the years into the process of making tahdig – one of most coveted treats in the landscape of Persian cookery.

Credits and Copyright

- All the photographs were taken by the author who owns the corresponding copyrights.

- All dishes depicted in this article were prepared by the author in a typical modern western home kitchen.

References

- Schoonover, David E., The Khwan Niamut: Or, Nawab’s Domestic Cookery, 1992, University of Iowa Press.

- Borjian, Habib, “Neṣāb-e Ṭabari revisited: A Māzandarāni glossary from the 19th century,” Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Volume 63, Issue 1, March 2020, pp 36-62.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qajar_dynasty, viewed September 22, 2020.

- https://fa.wikipedia.org/wiki/ته%E2%80%8Cدیگ , viewed September 22, 2020.

- https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1397/04/03/1759266/صادرات-ته-دیگ-ایرانی, viewed Jan. 16, 2021.