[The views expressed in this blog post are the author’s own.]

Reza’s story had to be told, not only for Iranians, but for the millions of Americans who are just like me–who hit the baseball, but ran to third base. For whom, Iran has been banished in the 1979 shadows of blindfolded hostages and flaming American flags.

My journey into all things Iranian began sitting next to Reza Abedi at a Little League game in 2004. Reza and I taught at the same high school and since our sons played on the baseball team together, we found ourselves having a casual conversation on a lovely Spring Saturday.

A conversation that changed my life.

Reza shared with me that he “ran to third base” the first time he hit a baseball.

“Third base?” I asked. “Why’d you run to third base?”

“No one told me,” he said with a grin, “to go to first.”

“You must have been really young.”

“Not really,” he answered. “I was in college.”

He offered me sunflower seeds. I put out my hand and studied his face. He poured the silver seeds into my palm.

He ran to third base, I thought to myself. And he was in college.

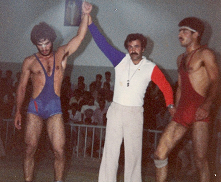

I recalled Reza sharing his gold medal from The Military World Wrestling Championship at a student assembly. He shared how he used to the opportunity of competing internationally to escape. I struggled to remember what else he had shared. As I did so, it occurred to me how much I really didn’t know. Wasn’t there a revolution in Iran? Didn’t they take our men as hostages? Yes, I recall the white rags wrapped around their faces. But what else did I understand?

My absolute ignorance regarding Iranian identity, culture, history and politics sent me running to third base. Humorous in a college baseball game, sure–but this misdirection in a historical context leads to dangerous and even fatal errors.

I raised my eyebrows. “So, no one played baseball in Iran?”

“Nope.” He shook his head. “Soccer, gymnastics and wrestling.”

“I remember you sharing your gold medal at the assembly,” I said with an attempt to sound like I knew something about him, about Iran.

He nodded.

“But,” I admitted, trying not to sound rude, “I don’t recall much after that. Would you mind… telling me a little bit about… you?”

As Reza shared vignettes of his life with me, I recognized my blinding ignorance.

Reza, one of 10 children born in Kermanshah in the 1960s, survived The 1979 Revolution, the Iran-Iraq War and made international news when he defected during the World Wrestling Tournament in 1982.

Then there’s my story–a girl from white-picket fence America in a household of 2.2 children, gold shag carpet and a station wagon. A girl who watched blindfolded American hostages and flaming American flags every night on the news. Who cried because she was afraid “Iranians” were under her bed–poised to kidnap her next. And who believed they hated her.

There on the Little League baseball field, it all changed.

Reza’s story had to be told, not only for Reza, but also for the millions of Americans who are just like me–who are running to third base. For whom, Iran has been banished in the 1979 shadows of blindfolded hostages and flaming American flags. And for whom the darkness held lessons unlearned.

We spent many more Little League afternoons and I hung on every word.

I learned not only about my friend Reza Abedi’s journey, but of millions just like him.

Reza’s family survived near starvation and violence in both The Revolution and Iran-Iraq War. At one point during the Revolution, Reza, his brothers, and other wrestlers, moved a bus missing two wheels to block access to their street to thwart raiders–both from the government forces and neighbors. They stormed stores for supplies and a prison for weapons. Then, in February of 1979, they welcomed the peace and promises echoing the end of The Revolution.

After The Iranian Revolution, Reza desired a fate beyond the suffocating constraints of Ayatollah Khomeini’s Iran. On the last night of the 1982 Military World Wrestling Championships in Venezuela, he gripped his gold medal knowing American wrestlers waited minutes away to help him and three others escape. Also knowing, his defection may mean the death of his imprisoned 13 year-old brother.

His description of the night he defected still gives me chills.

Reza’s incredible story propelled me through Iran and the 1979 Revolution. The journey taught me lessons I found both inspiring and interesting

How important are these lessons in America today? The question answers itself. I hear too often leaders compared to the well-known face of evil in Adolf Hitler, so much so, it is cliché. In doing so, an opportunity for discussion is missed. This dangerous penchant, reflective of both ignorance and denial, haunts every society who did not hear the warnings. Who do not learn the lessons.

Perhaps human nature drives us to be tribal–an ingrained DNA survival strand to form packs of “us” and “them”. But, perhaps, this fear-induced ideology is instead a learned behavior. A learned behavior howled in warnings by generations of artists, philosophers and historians who painstakingly continually reroute us as we crawl in our evolutionally attempt to become actual human beings.

I am reminded of the passage from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Two Towers:

“It’s like in the great stories, Mr. Frodo. The ones that really mattered. Full of darkness and danger they were. And sometimes you didn’t want to know the end. Because how could the end be happy? How could the world go back to the way it was when so much bad had happened? But in the end, it’s only a passing thing, this shadow. Even darkness must pass. A new day will come. And when the sun shines it will shine out the clearer. Those were the stories that stayed with you. That meant something, even if you were too small to understand why. But I think, Mr. Frodo, I do understand. I know now. Folk in those stories had lots of chances of turning back, only they didn’t. They kept going, because they were holding on to something. That there is some good in this world, and it’s worth fighting for.”

So too, the attempt of our journey–all of our journeys. The heart in Reza’s narrative connects humanity. My experiences impart wisdom.

It is in what Reza said to me just before he rose to speak before an auditorium of high school students, “Iranians are just like Americans,” he smiled. “Except you speak with funny accents.”