By Firouzeh Nabavi

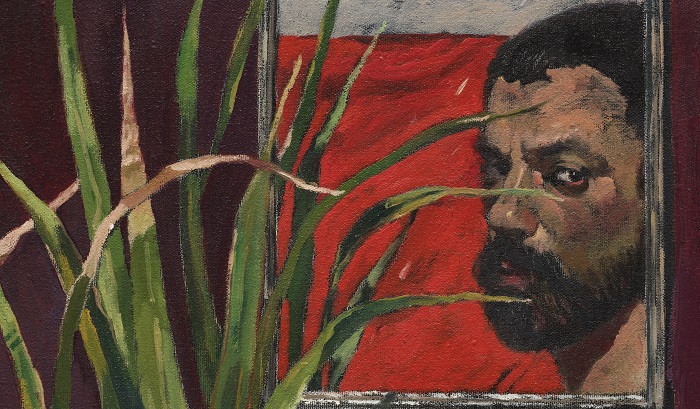

In 1980, a year after the Islamic Revolution, an exhibition of works by the painter Nicky Nodjoumi at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art was vandalized and shut down because of its “treasonous” content. The artist fled the country to join his family in the United States, leaving more than 100 artworks behind — and unaccounted for.

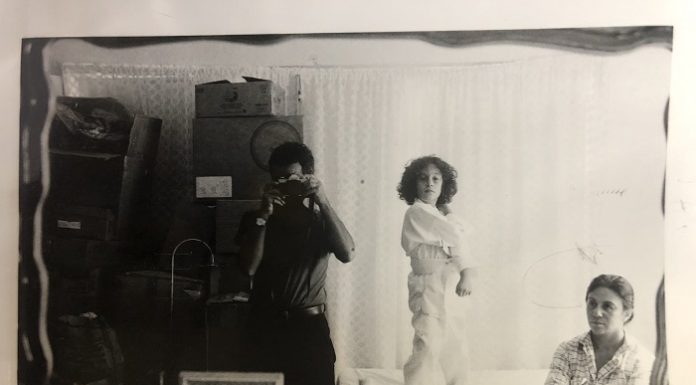

In the new documentary “A Revolution on Canvas,” the painter and his daughter Sara embark on a quest for the missing paintings from their home in New York. Directed by Sara Nodjoumi and her husband Till Schauder, the film is a moving portrayal of a family whose destiny is upturned by an art exhibition.

“A Revolution on Canvas” had its European festival premiere on March 16 at the Barbican in London as part of the Human Rights Watch Film Festival.

Sara Nodjoumi recalled that for more than 40 years, she heard her father tell the story of his Tehran solo show to anyone who would care to listen.

“In hindsight, it’s not surprising that he obsessed over that exhibition. It changed the trajectory of his life, indeed that of our entire family,” she explained in the production notes.

When she and her husband started making documentaries connected to Iran a decade ago, people repeatedly asked her why she didn’t make a movie about her father, a painter born in 1942 whose Brooklyn studio is filled with innumerable rolls of canvas.

“Given that he hates talking about his art, and even more so about his personal life, it felt like an overwhelming endeavor,” she said. “Finally, as he grew older and mellowed out a bit, Till and I decided to forge ahead.”

The movie looks back on Iran’s contemporary history using documentary footage and through interviews with Nodjoumi and Nahid Hagigat, the outstanding painter and artist to whom he was married until their divorce in 2003. There are also touching scenes with their two grandchildren, who have amusing reactions to their grandfather’s art.

As the documentary recalls, Nodjoumi is a young student and democracy activist in New York when he heads back to Iran in the 1970s, producing artworks and posters that are critical of the government, and which lead to his brief detention and interrogation by the security services.

He leaves Iran for New York, but decides to go back in 1980, believing that the Revolution marked the dawn of freedom and democracy in his homeland.

“That was not the revolution that we wanted,” he recalls in a scene from the documentary. “The justice that we wanted was not happening here. This was much worse than what we had before.”

The director of the Tehran Museum invites him to put on an exhibition, given that his work is “anti-Shah,” he recalls in the documentary. The show contains paintings picturing Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, angry men, and scenes of blood and fury.

As soon as the show opens, it is violently attacked in a newspaper article as the work of an Iranian who has come back from the United States and stabbed the revolution in the back. It is then vandalized and shut down, with no indication as to the condition or whereabouts of the artworks on display.

The Human Rights Watch Film Festival, established in 1988, has presented some 1,000 independent films in more than 30 cities around the world. The festival is closing as a result of a financial restructuring of Human Rights Watch.

“A Revolution on Canvas” is available for screening on HBO and other streaming platforms in the U.S.