By Kayhan Life Staff

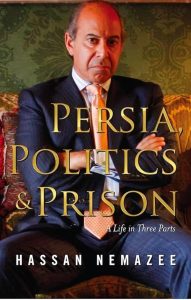

Hassan Nemazee, the Harvard-educated Iranian entrepreneur who served time in prison in the United States on financial charges, has just released his memoir “Persia, Politics & Prison: A Life in Three Parts” in which he reflects on a life marked by power, loss and transformation.

The book was recently launched at an event at the Lotos Club in New York.

The former multimillionaire was convicted of defrauding banks of nearly $300 million in 2009 and served a 12-year sentence.

Nemazee was born in 1950 and grew up in a privileged environment in the United States, attending reputable schools and socializing with the U.S. and Iranian elite from a young age. The Nemazees were a prominent family of merchants originally from the city of Shiraz in southwestern Iran.

Nemazee’s grandfather, Mohammed Hassan Nemazee had left Shiraz for Bombay in his early 20s in 1870 to establish a successful trading business between the two cities, before moving to Hong Kong. His father, Mohammed Nemazee took over the company at 26 and shifted its core business from trade to shipping, before leaving Hong Kong for America following the Japanese occupation of the British colony.

Both were philanthropists who sought to give back to society and were held in great esteem by the people of Shiraz and Iran as a whole. According to Nemazee, his grandfather established the Nemazee Clinic – a 50-bed charity healthcare facility in Shiraz in 1924 – while his father gave away as much as 90 percent of his wealth to his philanthropies, including close to $15 million to turn the clinic into the state-of-the-art 250-bed Nemazee Hospital and Nursing School in 1955.

“I have known many brilliant men and women in my life, from professors at Harvard to CEOs of companies and world leaders, but few matched my father’s range of curiosity and knowledge,” writes Nemazee in the book. Yet “he was never one to flaunt his erudition,” he adds. “He was humble in a way that is unusual in people who achieve so much. I never met another man who could dominate a room so forcefully by saying so little.”

Losing his father just before graduating from Harvard at 22, Nemazee returned to Iran in 1972 to take on his responsibilities as heir. He would spend the next six years there, partnering with major international businesses in real estate development, insurance and banking.

“Iran was thriving, and I was eager to thrive with it,” he writes. His background, youth and drive perfectly positioned him to do so: an American-born, American-educated Iranian, with “a family name that opened doors in Iran and elsewhere.”

That is, until the advent of the Revolution — when those same privileges suddenly became liabilities, and all of his personal holdings were nationalized in 1979. Nemazee, who was married by then, left Iran for the United States soon afterwards, starting over in New York City, and rebuilding his life and wealth in the U.S.

He would later get involved in political fundraising and, by 1996, establish himself as one of the leading fundraisers in the Democratic party.

In 2009, however, Nemazee was sentenced to 12 years in prison for orchestrating a scheme that defrauded Bank of America, Citibank and HSBC of $292 million. According to the sentence, the funds were used to buy and maintain luxury properties, make financial investments and contribute $2 million in political donations and charitable gifts.

Nemazee served his prison term at a low-security facility in Texas, and in prison camps in New York and Maryland. He was released in 2019 to serve the rest of his sentence in home confinement. He wrote his memoirs while in prison.

In a recent interview with Kayhan Life, Nemazee looked back on his life and times in Iran.

You were born into an affluent family, attended elite U.S. universities, and frequented the Iranian and American elite from a young age. How did those experiences shape the man that you are today?

I have had many advantages in life. Born into affluence, educated at the best schools, with proximity to leaders in education, business and government both in America and Iran. However, my greatest advantage was the love and guidance of both my father and mother. My father was the most humble man I have ever known, yet he always commanded a room by his calm and intelligence. My mother taught me the importance of determination and patience in life and business.

Your grandfather and father were respected industrialists, and philanthropists who believed in the importance of giving back. What personality traits did you inherit from them? And your father once advised you never to flaunt your wealth – have you followed the advice?

The concept of giving back was ingrained in me from my youth. Obviously, I saw the impact and importance of the various charities that my father had founded: the Nemazee Hospital, Nemazee Nursing School, Shiraz Water Works, Iran Foundation, Nemazee Vocational School, Nemazee High School as well as the Nemazee Trust. I knew that my grandfather had established the first modern medical clinic in Shiraz, but was unaware until I did research for this book in Hong Kong and India that he had established charitable organizations over 100 years ago.

As to the question of whether I followed my father’s advice not to flaunt my wealth, I hope that I have, and that I have instilled the same belief in my children.

The loss of your father just before you graduated from Harvard at age 22 was a defining moment in your life. You had to decide whether to continue studying in the US or return to Iran and take over his responsibilities. How do you look back on the six years (1972-1978) that you ended up spending in Iran? To what extent was your job made easy by your father’s board members, friends and entourage?

There is no question in my mind that the six years that I spent in Iran were extraordinary. The opportunity to attend Harvard Business School directly out of college was compelling, but those six years in Iran put me in a totally unique situation. The ability to negotiate joint venture deals with major international businesses such as American International Group(AIG) and Morgan Guaranty Trust among others was far more valuable than an MBA from Harvard. Additionally, I was able to experience the extraordinary years of Iran’s unprecedented growth and subsequent revolution personally. That was an experience that could never be taught in Harvard case studies.

I could never have accomplished the things that I did without the benefit of the advice, guidance, and support of my father’s many friends, who were instrumental in helping me determine my path and implement my decisions. They included Hushang Ansary, Asadollah Alam, Abol Hassan Ebtehaj, Majid Majidi, Khodadad Farmanfarmaian, Syed Jalal Tehrani amongst others. I would spend hours listening and learning.

Within a few years of your father’s passing, you became an astute businessman yourself, successfully setting up businesses in real estate and insurance, and persuading the head of the Morgan Guaranty Trust of New York’s international division to set up a commercial bank in Iran. How did you do that? Was this a manifestation of the hubris which you observed in Iran and which, as you explain in the book, you later embraced?

As I wrote in the book, my grandfather took an extraordinary risk in leaving Iran and establishing a flourishing business in India and then China. My father became the most successful businessman in shipping in Hong Kong when he was still in his twenties. He had the foresight to invest in Liberty ships post WWII and sell them prior to the Korean War.

What I tried to do in those six years in Iran pales in comparison to what my grandfather and father risked and reached for in their lives. I was fortunate to be living at a unique time in Iran’s business history. The opportunities were immense. The risks were commensurate. I saw the opportunity of investing in a bank, an insurance company, and real estate at the same time. Had the Revolution not occurred, this combination would have been unique. My hubris came later in life, as a result I think of my earlier successes.

You write that the 1973 oil crisis was financially and culturally disruptive to Iran, and “would ultimately cost the Shah his throne.” What should the Shah have done differently under the circumstances?

The increase in oil prices in the 1970s was necessary for us to regain control of our oil income. In my book, I describe the economic disruption that resulted in the Revolution. Hindsight is 20/20, so it’s somewhat disingenuous to criticize decisions made fifty years ago, but one can reflect and opine on the consequences of those decisions. I believe Iran would have been better served to have moderated its development plans in a manner that would have avoided excessive inflation and massive population movements from rural to urban centers, and built sufficient infrastructure to support the massive spending that the Shah undertook. I also believe that Iran should have established a sovereign wealth fund, as some were advising at the time.

President Jimmy Carter recently died at age 100. On one of your last Washington stays before the Revolution, you met with former CIA director and Ambassador to Iran Richard Helms, who was deeply upset by events, and said the Shah was receiving conflicting advice from the Carter administration. What else did he tell you in that conversation?

Candidly, I went to see Helms because of my personal friendship with him and my concern for him after the Church commission which had been investigating Helms for lying to Congress about the CIA’s involvement in the killing of President Salvador Allende in Chile. I firmly believe that Helms would have provided better insight to the White House, State Department and the intelligence community as well as to the Shah had he still been in post in Tehran. Helms had years of familiarity with Iran which Ambassador Sullivan did not. It’s an unfortunate accident of fate that Helms wasn’t in Tehran in 1978.

As the political turmoil in Iran escalated, it became dangerous for you to stay. You write that you risked imprisonment or worse. How difficult was it for you to leave Iran?

I was lucky. As I write in the book, I was one of the first people to be placed on Iran’s version of the No Fly List. I was stopped from leaving on December 4, 1978. I called on every relationship that I had to try to get permission to leave. We received phone calls every day saying ‘We will kill you if you try to leave.’ It was clear that I was a target of someone.

Ultimately, I was interviewed by the Deputy Minister of Justice who gave me my exit visa. It was my insistence that he give me a letter to the police department that forced the police to release my passport on a Thursday afternoon. The police went on strike on Saturday until after the Revolution in February. Had I not obtained my passport on that day, there is no question in my mind that I would have been a target.

You later acknowledged your “complicity in the ills that had befallen the country,” and in supporting a system that served your interests and those of the Iranian business community. Looking back, what would you have done differently?

As I said, hindsight is easy after 45 years. The point I was attempting to make was that all of those of us who benefitted from our positions of power by and large didn’t engage in the political process. We abdicated that responsibility. I resolved not to repeat that in America, therefore my involvement in American politics.

Lastly, again it’s easy to opine now, but clearly from the Shah on down, the Iranian establishment wasn’t prepared to fight for its survival. As a result, we are where we are today.

All of your personal holdings were nationalized in the spring of 1979. Yet you write that, all things considered, you were fortunate, because “we had our lives and we had our freedom.” Do you believe you will ever go back to Iran? And would you like to live there?

I hope the reader believes that I am basically an optimist. As such, I’ve always believed that one day, we will all have an opportunity to return to Iran. I would certainly love to return to Iran with my wife Nazie Nemazee, our five children and all of our grandchildren. Change comes when least expected. Look at the collapse of the Soviet Union, or more recently the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria. Change is inevitable.

Do you have plans to publish “History of Civilization”, the manuscript written in Persian by your father in the last 10 years of his life, which was originally due to be edited by Ehsan Yarshater, Professor of Iranian Studies at Columbia University?

Professor Ehsan Yarshater edited my father’s book. The book was published by me some years ago in Farsi. The book is titled “Dastan Tammadon.” I was the Vice Chair of Encyclopaedia Iranica for some 15 years.