A new report by Amnesty International says human rights lawyers in Iran have been excluded from prison release schemes during the COVID-19 outbreak.

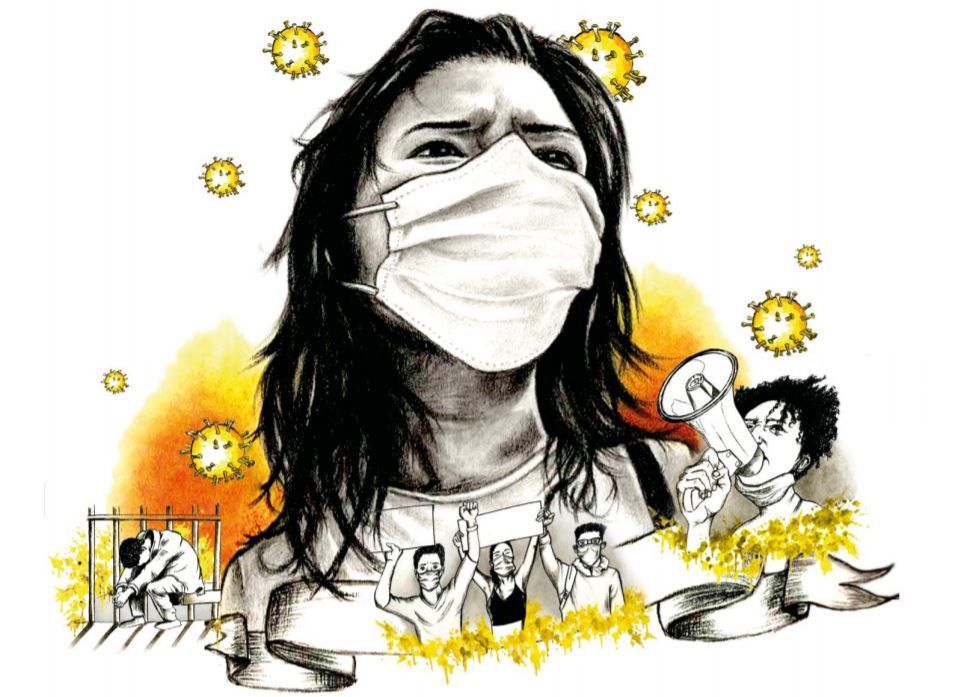

The report, entitled, “Daring to stand up for human rights during a pandemic,” analyzes the treatment of human rights activists by Iran and other countries during the pandemic.

While other states have implemented measures to depopulate prisons and stem the spread of the virus, human rights advocates held in jail in Iran have been denied conditional or temporary release, according to Amnesty.

Oscar Jenz, the Iran and United Arab Emirates Country Coordinator for Amnesty International UK, says the exclusions are a deliberate form of punishment for defenders who provide information on the Coronavirus pandemic and offer support to marginalized groups.

“The Iranian government is singling out human rights defenders. This is because over the past three to four years, authorities have had an increasingly hard time managing dissent against corruption, lowered living standards and, more recently, their management of the COVID-19 crisis,” he said.

“The Iranian government sees human rights defenders as an existential threat which endangers their authority, as they slowly lose control over the country,” he added.

After the sharp rise in Covid-19 cases in February, the Iranian government announced that it would temporarily release prisoners to reduce overcrowding and prevent outbreaks of the virus in detention centres across the country.

Amnesty’s report said that while the government had pardoned up to 10,000 prisoners and temporarily released 85,000 offenders, many human rights defenders and political prisoners had been excluded from the furlough and pardon schemes, including human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh and anti-death penalty activist Narges Mohammadi.

[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#0892d0″ columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” disable_bgshading=”off” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off” aesop-generator-content=”“In order to silence my voice, the Islamic Republic system has not spared me any violent action, from condemning me to lengthy imprisonment to depriving me of seeing my children or even hearing their voices on the phone to beatings, exile, insults and assaults on my dignity… What keeps me on my feet … is my love for the proud and tormented people of my country, and for the ideals of justice and freedom. Until my last breath, I will not stop speaking about justice, crying out against oppression, defending those who seek justice and freedom, and demanding the realization of sustainable peace.” [Narges Mohammadi]”]

“In order to silence my voice, the Islamic Republic system has not spared me any violent action, from condemning me to lengthy imprisonment to depriving me of seeing my children or even hearing their voices on the phone to beatings, exile, insults and assaults on my dignity… What keeps me on my feet … is my love for the proud and tormented people of my country, and for the ideals of justice and freedom. Until my last breath, I will not stop speaking about justice, crying out against oppression, defending those who seek justice and freedom, and demanding the realization of sustainable peace.” [Narges Mohammadi][/aesop_content]

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/narges-mohammadi.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Narges Mohammadi. Source: Kayhan London” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Sentences for human rights defenders have also increased sharply since 2018, after demonstrations in Iran intensified over government corruption, unpaid wages and economic mismanagement. Mr. Jenz said the disproportionate sentences were a defensive measure by Iranian officials.

“Sentences for human rights defenders over the last two years have really snowballed out of control. These protests are only increasing, and so the government is trying to put all human rights defenders out of action before they can become focal points for mobilization and movement across the country,” he said.

The report also offers examples of sentences for human rights defenders being extended, often just before their release date. Human rights campaigner Atena Daemi, who was due to be released on July 4, was sentenced to two additional years in jail and 74 lashes in June, for engaging in human rights activism while in prison. The report adds that Daemi’s family believe the charges are unjustified and designed to keep Atena in prison.

Jenz is also concerned by the rise in secret executions, which he says form part of the Iranian government’s current attempts at stemming dissent.

“We are seeing a rise in secret executions which is unprecedented and a clear sign that the government is becoming increasingly desperate. The government is delaying telling the families of prisoners that a relative has been executed, and in some cases not releasing bodies, because public funerals and mourning rituals have become focal points for resistance and anti-government sentiment,” he explained.

Instances of Iranian officials denying medical assistance to human rights defenders with health conditions or COVID-19 symptoms were outlined in Amnesty’s report. Narges Mohammadi, who has a pre-existing lung condition, was repeatedly denied medical treatment for a suspected COVID-19 infection, according to the report.

Iranian officials have targeted human rights defenders living abroad as well. In an opinion piece published in the Washington Post on August 11, Masih Alinejad, a campaigner against the compulsory hijab, said the Iranian government had launched a social media offensive on Twitter announcing an intention to kidnap her for engaging in activism.

Alinejad’s piece went viral, and several social media users on Twitter — including the London based International Observatory of Human Rights — called on the platform to take down the campaign.

In this video, I explain how kidnapping & hostage-taking are some of the tools the Islamic Republic of Iran uses for diplomacy.

I call on the the international community to take it seriously.

In addition to calling for my kidnapping, the regime recently kidnapped 2 dissidents pic.twitter.com/Icbq7BCZMA

— Masih Alinejad ?️ (@AlinejadMasih) August 11, 2020

Amnesty’s report includes recommendations to protect human rights defenders during pandemics in countries like Iran. The recommendations ask states and members of the public to protect and enable human rights defenders so they can carry out their work safely and ensure the most vulnerable in societies across the world are supported.

Jenz said that while the international community had a duty to upbraid the Islamic Republic on its treatment of human rights defenders, the most effective way to hold power to account was through individuals in society coming together to press their governments to act.

“International bodies must take these cases seriously and hold Iran accountable. However my advice would be, don’t wait for governments: governments are mired in their own problems. It’s up to us as individuals, as human beings, to take on this mission,” he said.