By Nazenin Ansari and Firouzeh Nabavi

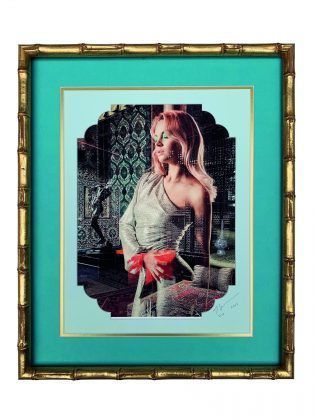

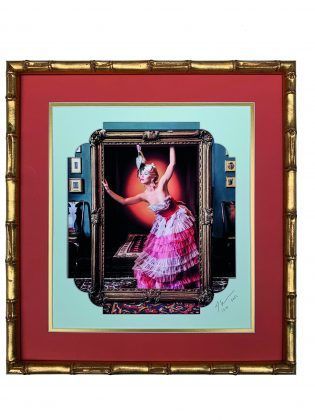

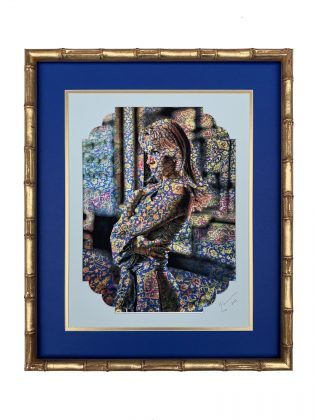

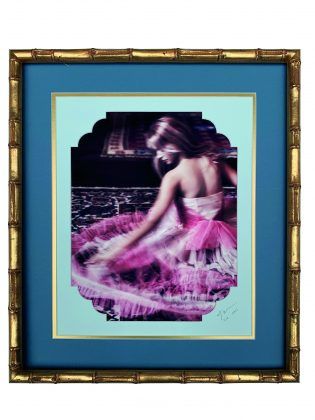

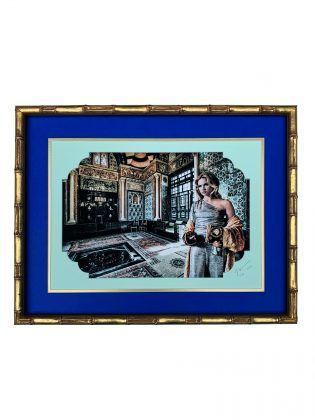

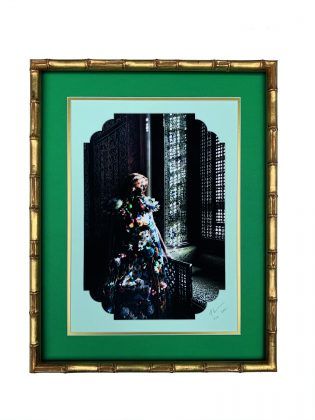

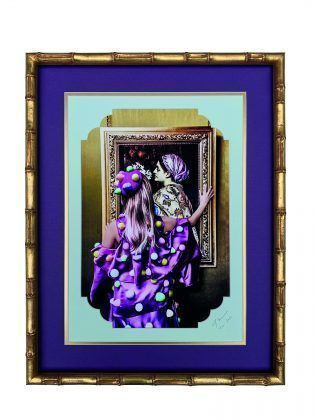

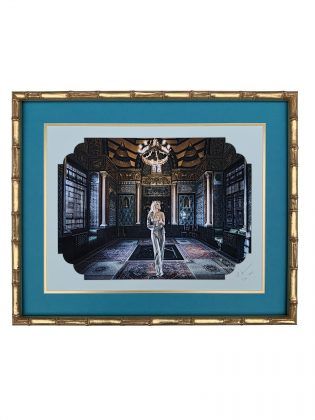

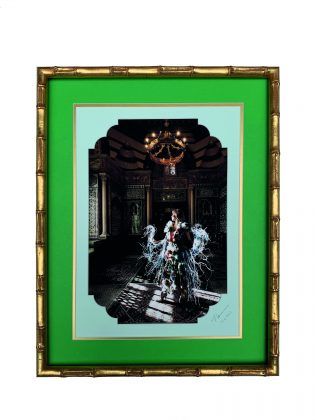

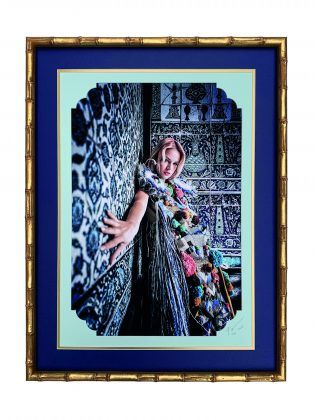

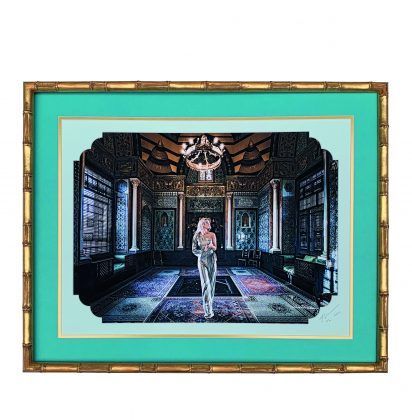

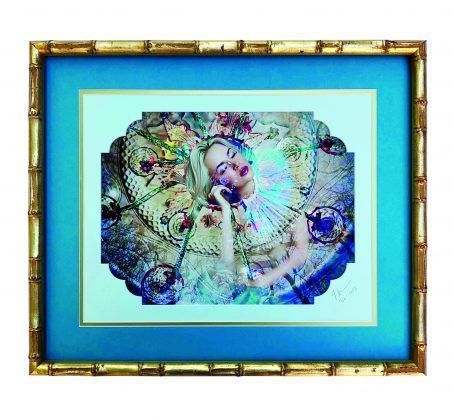

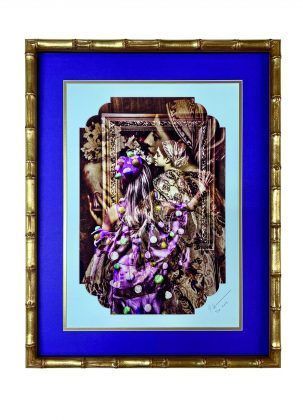

Maryam Eisler, the Iranian-born arts patron and photographer, has released a new series of photographs which recently went on show at Linley, the London gallery established by David Linley, the nephew of Queen Elizabeth II.

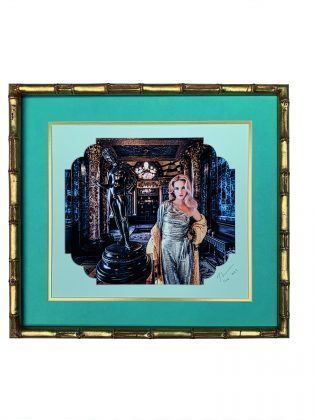

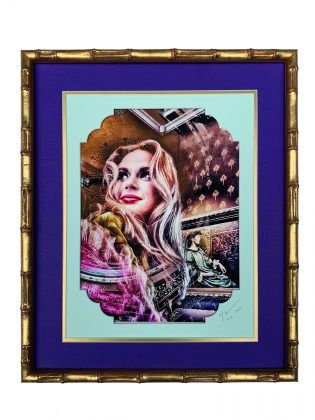

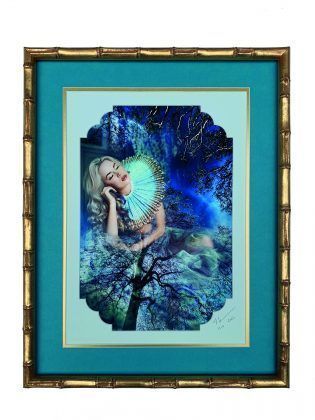

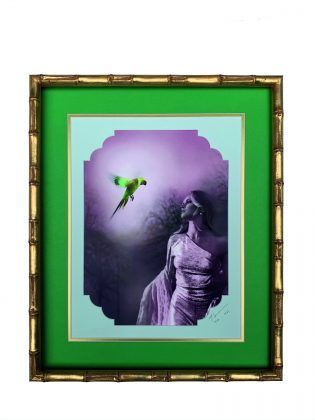

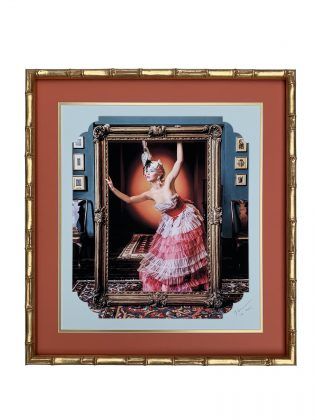

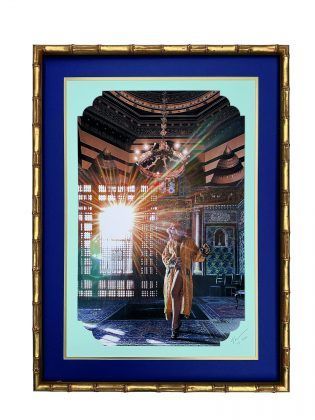

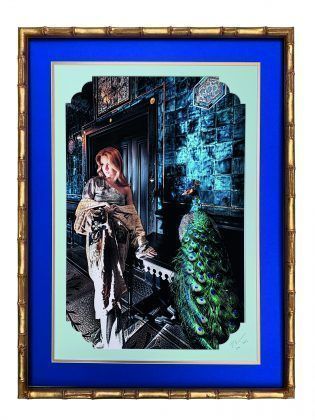

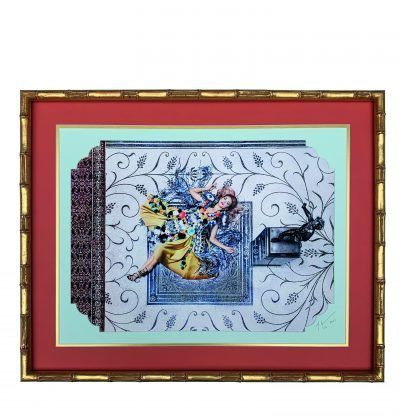

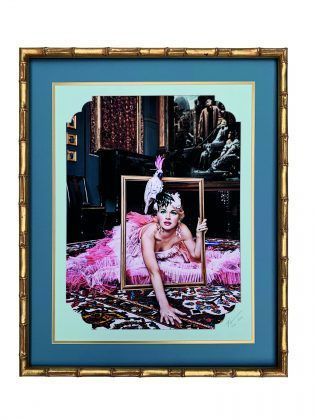

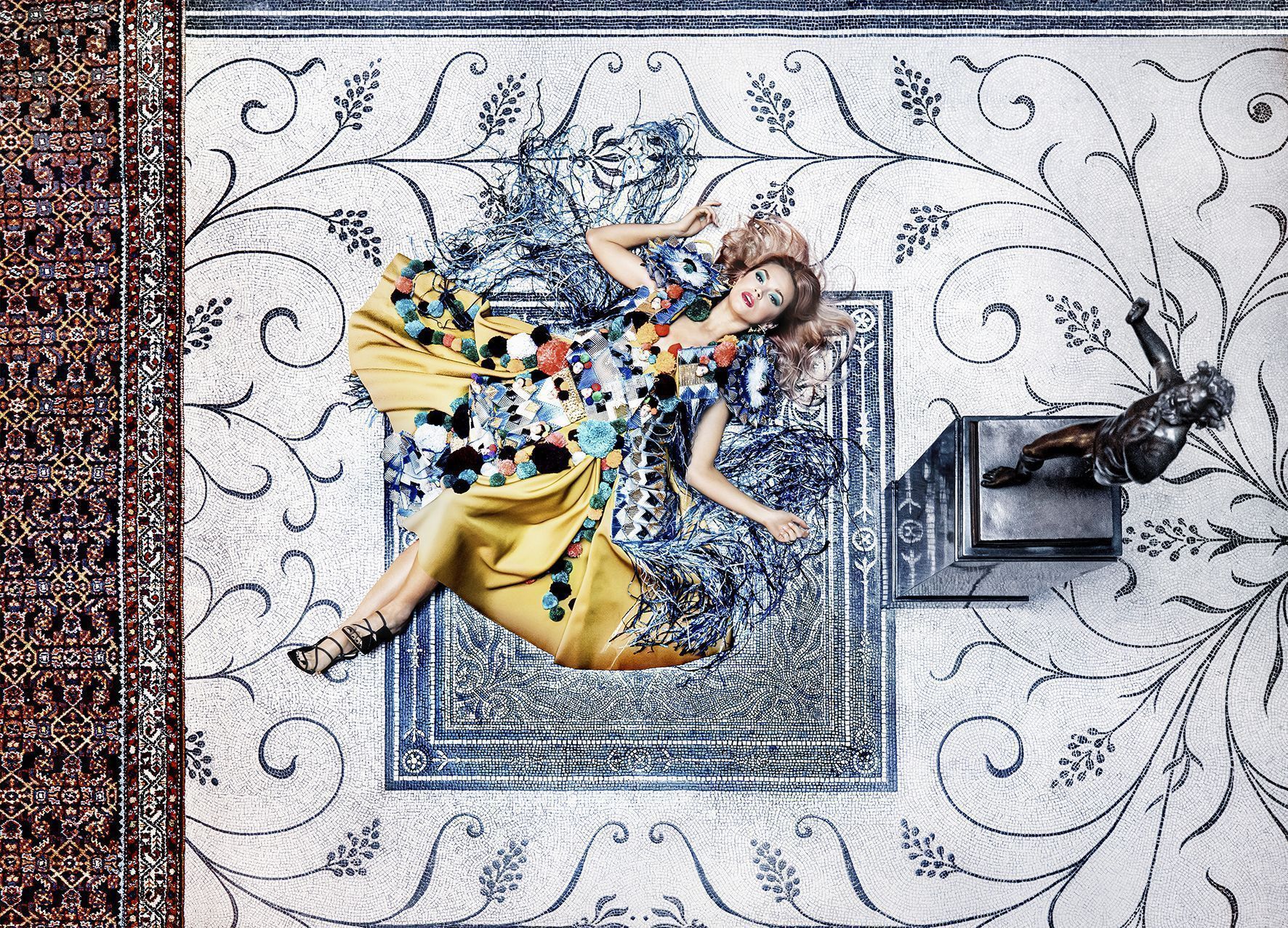

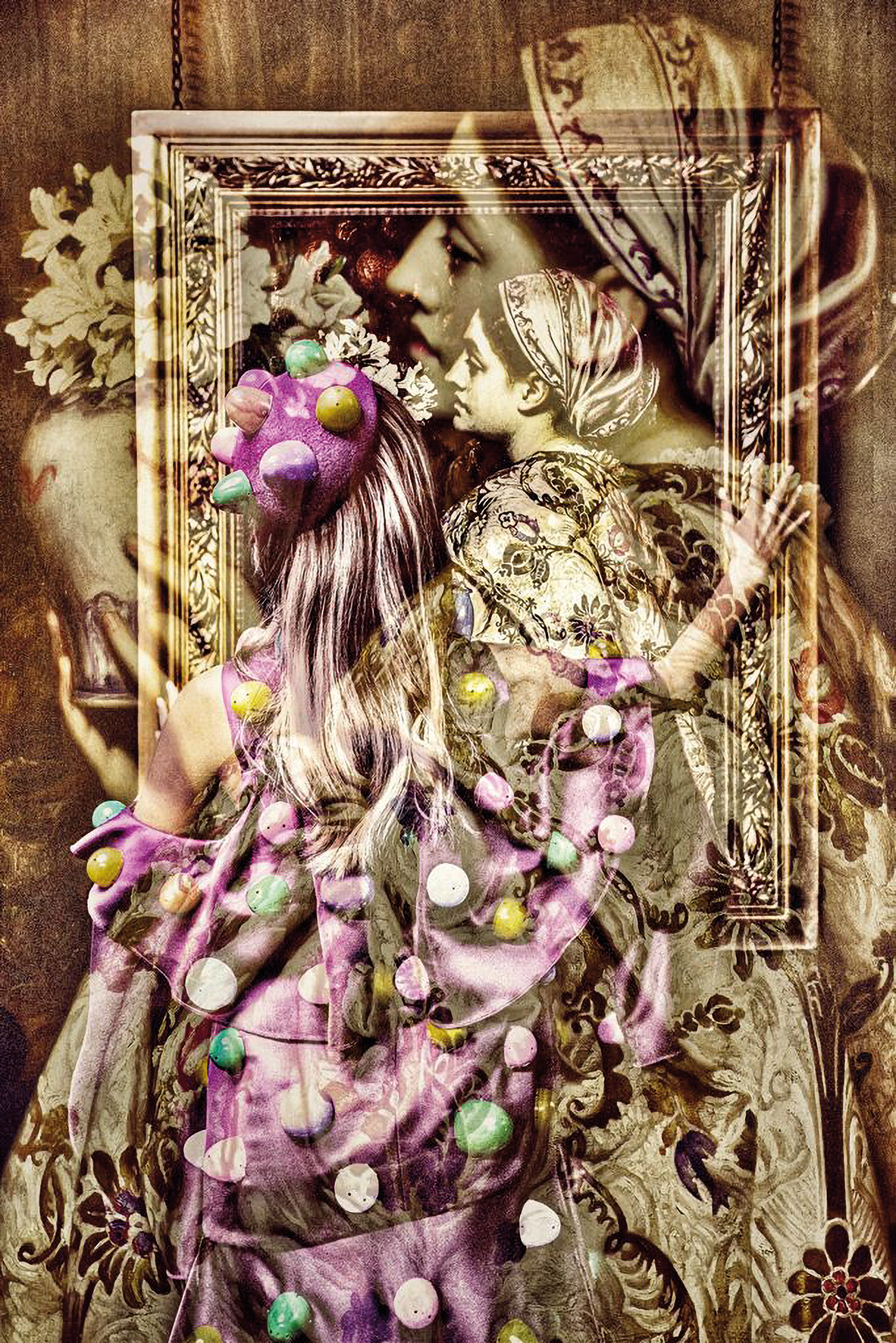

The photographs are a fusion of East and West, and were shot inside Leighton House: the grand London home of the Victorian-era artist Lord Frederic Leighton, which has an abundance of Middle Eastern ceramics and an ornate Arab Hall.

“Once Upon A Turquoise Past” is the latest in a series of London exhibitions by Ms. Eisler. Previous shows featured black-and-white photographs of female bodies and landscapes in the American West, inspired by the work of the 20th-century American photographer Edward Weston.

Ms. Eisler grew up in Iran, and after the Revolution, moved to Paris with her family. She studied at Wellesley College and Columbia University, and got her first job at L’Oreal in London in 1993. She later transferred to New York to take up another L’Oreal position, married and returned to London where she still lives and works.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/WhatsApp-Image-2021-12-07-at-5.24.09-PM.jpeg” panorama=”off” credit=”Photo credit: Maryam Eisler” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” caption=”Portrait of Maryam Eisler in her exhibition at Linley. ” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Kayhan Life interviewed Ms. Eisler inside her exhibition at Linley.

How did this new photography series come about?

I was sitting at home during lockdown in November 2020. I had a lot of time on my hands. I was playing around a lot with Roloff Beny’s book “Bridge of Turquoise” — taking out my Barbie dolls from when I was little, placing them in front of pictures of Persepolis and of the tomb of Hafez and then shooting them on an iPhone. It made me very melancholic and nostalgic about not having been able to see these places. I got a sense of lost splendor.

The other obsession I’ve always had are the Henry Clark photographs of Marisa Berenson and Lauren Hutton which he took in 1969 for US Vogue. They reminded me of that romanticized vision of the Iran that I grew up in, and the way the West looked at the East. I thought to myself, I would love to have a dialogue with Henry Clark. Leighton House, near where I live, has always been a sanctuary for me over the years. I was desperate to get in there and do a playful shoot. I got in touch, and managed to get in. So we had a day of shooting with Sarah Lovegrove, a dancer I’ve worked with before.

What are the price points for these photographs?

The biggest photograph is 7,000 to 8,000 pounds. Prices start somewhere between 1,500 and 2,000 pounds.

What kind of crowd came to your opening night?

There were as many true collectors as there were social types. There were also a lot of museum people, from the Tate, the British Museum, the Whitechapel Gallery. You could argue that they were here because I’ve been supporting their institution. But it’s been seven years since my first public show, and I think I’ve finally managed to break the perception that I’m just doing this to have fun. This is all I do.

How did you meet David Linley and put on a show at his gallery?

At the opening of my last exhibition, of my photographs of Capri, which are now in a book. He came with Isabelle de la Bruyère from Christie’s. I had no idea that they were coming. He approached me and said: ‘I have a question to ask you. Do you have a series that you’ve never shown before?’ And I said: ‘Funnily enough, yes, I just shot a series at Leighton House.’ He said, ‘Would you consider showing it at Linley?’ And I said, my goodness, yes.

The series wasn’t yet ready. He didn’t know what it was going to look like. He just said, ‘I love what I’m seeing.’

At Linley, people come in, they see the art. Some of them buy the art, some of them buy lovely stuff on sale at Linley, because it’s Christmas time. It’s a lovely relationship to have.

What was it like dealing with David Linley, a member of the British royal family?

He is super friendly, and so nice. He’s open to new opportunities, and unbelievably modest and low-key. If I send a text, he responds within two minutes. There are no airs and graces whatsoever. He has a true desire to activate the space.

Who are your collectors?

I can comfortably say that about 60 to 70 percent of my collector base is from America. There are lots of Americans in London. The rest are international, very international: the expat base here in London. Europeans, South Americans, Lebanese…

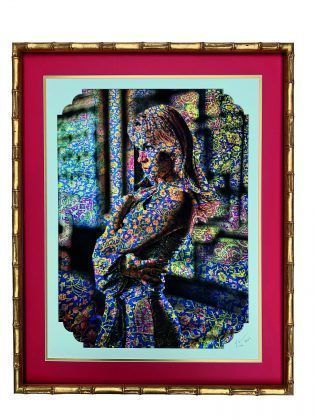

And I would say about 10 to 15 percent of my collectors are Iranian. The times when I’ve noticed a lot of Iranian interest have been when I’ve done collaborations — for example the stamp series I recently did with the Magic of Persia Foundation.

During lockdown, I found old Persian stamps that I had bought about 22 years ago. They were Iranian stamps from the early 1900s to the Revolution. I had time to reorganize. I took all the pretty ones and started collaging them, superimposing them, etc. and created new stamps based on the past, but focusing on things that no longer exist: such as the Iranian female football team, or other examples of female power.

We created a series based on these new stamps. And they sold very well. So we were able to support three residencies for Iranian artists at the Delfina Foundation in London, which runs prestigious artist residencies and is led by Aaron Cezar. The stamps were all sold online.

What are you going to do next?

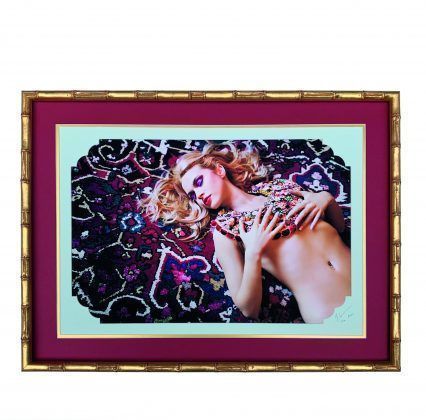

I just came back from France two weeks ago. I was in Arles, in southern France, and spent a week at the Nord Pinus Hotel. The photographer Peter Lindbergh lived in one of the suites. Pablo Picasso spent a lot of time there. Helmut Newton took his famous shot of Charlotte Rampling there. I was there in the summer and approached the management of the hotel and asked if I could shoot there. It took three months. I finally got a call in September saying: ‘We’ve reviewed your work, and we would love for you to come down.’ I spent six days there. We just went down with two models and one assistant, and just played. We were very inspired by Helmut Newton.

The management of the hotel took a huge interest in what we were doing, and I got a call saying: ‘Perhaps you should also do something in the arena,’ the bullfighting ring. So they called the mayor’s office and got me to the arena.

How do you feel about living and working in the UK? It’s not the best market for photography.

That’s true, and it’s a big problem as a photographer functioning out of London, where there’s a big focus on contemporary art, but photography doesn’t play any role in the market at all. That’s why my collector base is not English, because I don’t think they buy a lot of photography. In London, you need to work a lot harder at convincing people that photography is actually an art form. The Photo London fair has helped, it goes without saying, and there’s the Photographers Gallery, but it’s challenging for everyone.

Another problem for professional photographers is smartphone cameras and Instagram. All of us are bombarded with so many images every day that professional photographers’ images get lost. Can you talk about your own relationship with Instagram?

I’m actually still private on Instagram, not public. But I think that I have the right 3,500 followers, a very art-world-led group — people who really like art and photography — and I have a nice dialogue with them.

Instagram has been an amazing tool for marketing. In fact, I pretty much only use it for marketing my photographs, my new series, the books I’ve made, tying it all together.

During the pandemic, we had an immense amount of sales that took place simply through Instagram. People were bored. They were sitting at home flipping through savings, through cash, because there wasn’t much to spend money on outside. So they ended up buying art.

On the flip side, there are other very different Instagram accounts, and most of them get on my nerves because it’s all about ‘me.’ Are people really interested to see what you ate last night or know where you have been on holiday?

But I think if you use Instagram as a promotional tool, it does wonders.

In terms of your patronage of arts and arts institutions in London or elsewhere in Europe, is that something that you’re continuing?

I love the arts, and will always hold the Tate very dear to my heart, because I had a wonderful 10-year experience with them co-chairing the Middle East acquisition committee. I stepped down a year and a half ago.

Nowadays, I don’t collect any more at all. I don’t have the time, because all of my time and focus is on my photography.