By Kayhan Life Staff:

The Bertelsmann Foundation recently released its biennial report on non-democratic countries such as the Islamic Republic of Iran.

The foundation was established in 1977 by Reinhard Moon, the founder of the Bertelsmann international publishing house in Germany.

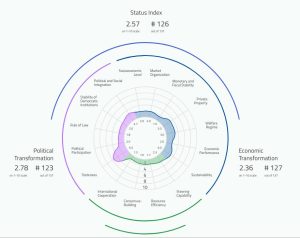

The 42-page report on Iran, which features statistical charts, includes a detailed analysis of the “political evolution,” “economic evolution,” “government” and “government performance” of the country.

Below are relevant extracts from the report, which begins with the protests in Iran that followed the September 2022 killing of Mahsa Jina Amini: BERTELSMANN REPORT EXTRACTS

In September 2022, Iran witnessed the emergence of its most significant wave of protests, demanding regime change, in recent years. Unlike the street protests in 2009, 2018 and 2019, the “woman, life, freedom” movement encompassed various social classes. By early 2023, the government had temporarily quelled the street protests. However, a renewed wave is likely, given the government’s failure to adequately address the basic economic needs of an increasing portion of society. The outcome of this revolutionary process, which marks an irreversible divide between the state and society, hinges on whether the regime, resistant to meaningful political and economic reform, or the protesters will prevail.

In the June 2021 presidential elections, ultra-conservative Chief Justice Ebrahim Raisi emerged victorious. He was essentially hand-picked by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in a heavily managed electoral race that favored the elite hard-line faction. This came amid widespread disillusionment with the performance of his predecessor, the so-called moderate Hassan Rouhani. The monopolization of power by the broader conservative camp – encompassing traditional conservatives, ultra-conservatives, fundamentalists and extremists across the Islamist political spectrum – extended into the political sphere following the elections. The conservative camp had already exerted dominance in other critical areas of state and semi-state power, including the judiciary, intelligence services and various key political, economic and military entities.

By early 2023, halfway through President Raisi’s four-year term, the country faced its most severe political and economic crisis since the 1979 revolution. Economically, internal mismanagement and corruption worsened under an administration perceived as highly inept and driven by ideological zeal. It dismissed the remnants of technocratic expertise that were still present during Rouhani’s tenure, albeit tainted by corruption. Consequently, the national currency’s decline intensified, with the official inflation rate reaching approximately 50% (though the real rate was likely double that figure). Socioeconomically, poverty continued to expand, affecting larger segments of Iran’s increasingly diminished middle class. High inflation disproportionately impacted essential expenses for economically vulnerable households, despite the Raisi administration’s promises to combat poverty. Meanwhile, despite the failure to revive the nuclear deal and the ongoing U.S. economic sanctions, Iran managed to increase oil exports, primarily through an illicit international network. This resulted in a four-year high in oil exports to its main customer, China, by early 2023.

The report follows with an analysis of the socio-economic situation of the country: Iran’s socioeconomic crisis has steadily worsened in recent years, leading to extensive protests that have often taken on a political dimension. While the Islamic Republic ranks 76th in the 2021 Human Development Index (HDI) with a score of 0.774, placing it in the “high human development” category, Iran’s Gender Inequality Index score of 0.459 contributes to an overall HDI loss of 11.4% due to inequality. In 2019, the World Bank reported that 6.0% of Iranians were living on less than $3.65 a day at 2017 international prices adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), while Iran’s Gini coefficient was 40.9 in the same yearThen it continues:Iran’s high Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rate, which reached 43.4% in 2021, impacts lower-income households particularly hard. Prices for essential goods, such as food items, surged 86% by the summer of 2022, marking a decade-high increase.

The report follows with an analysis of the socio-economic situation of the country: Iran’s socioeconomic crisis has steadily worsened in recent years, leading to extensive protests that have often taken on a political dimension. While the Islamic Republic ranks 76th in the 2021 Human Development Index (HDI) with a score of 0.774, placing it in the “high human development” category, Iran’s Gender Inequality Index score of 0.459 contributes to an overall HDI loss of 11.4% due to inequality. In 2019, the World Bank reported that 6.0% of Iranians were living on less than $3.65 a day at 2017 international prices adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), while Iran’s Gini coefficient was 40.9 in the same yearThen it continues:Iran’s high Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rate, which reached 43.4% in 2021, impacts lower-income households particularly hard. Prices for essential goods, such as food items, surged 86% by the summer of 2022, marking a decade-high increase.

Simultaneously, Iran’s wealthy citizens, many of whom have ties to the regime, have seen their fortunes rise. Forbes reported in June 2021 that the number of high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) in Iran increased by 21.6% in 2020, significantly exceeding the global average of 6.3%. The collective wealth of these U.S. dollar millionaires grew even faster at 24.3%.

While the official unemployment rate stood at 9.2% in spring 2022, the real rate is believed to be much higher, possibly twice as high or more. According to data from the Statistical Center of Iran (SCI) in late 2021, the overall unemployment rate for 18- to 35-year-olds increased from 15.6% in spring 2021 to 17.6% in summer 2021. During the same period, the unemployment rate for men in the same age group rose from 12.9% to 14.6%, while for young women in the same age group, it increased from 27.8% to 31%. In summary, the Islamic Parliament Research Center corrected the overall unemployment rate in November 2020 from 9.8% to a staggering 24%. Some economists suggest an even higher rate, possibly up to 40%.

The situation is particularly dire for Iran’s rural youth. Over the years, Iran’s rural population has decreased from approximately 50% in 1979 to about 25% in the early 2020s. A staggering 22% of the world’s most affected rural youth live in Iran, according to the 2019 Rural Development Report.

Iran’s labor market exhibits significant gender gaps, including a low female participation rate. According to the SCI, the labor force participation rate of women aged 15 and above stood at only 13.8% in the first quarter of the Iranian year 1400 (March–June 2021), while the male participation rate reached 68% for the same period. In other words, the female participation rate was just one-fifth that of men. Furthermore, according to International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates, the female workforce participation rate in 2021 was a mere 14.35%, while the rate for men was five times higher at 68.09%.

The Bertelsmann Foundation report also highlights the non-compliance with the laws of the Islamic Republic itself by those who govern the country:

Like many other constitutional principles in the Islamic Republic, the separation of powers exists only on paper. The supreme leader directly or indirectly appoints the heads of all three branches of government. The powerful, hard-line-dominated Guardian Council vets parliamentary and presidential election candidates.

There are rivalries among the various branches of the state, especially when a president hailing from the reformist or “moderate” elite faction is faced with mostly hard-line-dominated bodies. This can result in the administration’s agenda being undermined.

In reality, the supreme leader’s quasi-omnipotent status, a highly politicized judiciary and the absence of the rule of law collectively contribute to the dismal state of the separation of powers in Iran.

In addition, the creation of new bodies such as the Supreme Council of Economic Coordination, which includes the supreme leader along with the heads of the three branches of government, further undermines the separation of powers. In November 2019, the Supreme Council of Economic Coordination decided to triple fuel prices overnight, thereby kicking off nationwide street protests.

Article 57 of the constitution provides the supreme leader with far-reaching supervisory powers over judicial institutions. The supreme leader appoints and dismisses the country’s chief justice, who is responsible for appointing and dismissing judges. The supreme leader also appoints the chief of the Supreme Court and the attorney general, in consultation with the judges of the Supreme Court. As such, the judiciary is not an independent institution, nor are the judges. Even the minister of justice has little influence in this sphere, compared to the supreme leader.

As bailiffs, the IRGC and especially their dreaded intelligence organization (Sâzmân-e Etelâ’ât-e Sepâh) have a strong influence on the course and outcome of legal processes. Forced confessions through brutal torture are common, especially in the cases of civil society and human rights activists, as well as protesters.

Intelligence organizations are also strongly involved in detaining dual nationals, who usually have no access to diplomatic or consular protection. Since 2015, at least 30 people with dual nationality have been imprisoned, many from European countries, among them the Iranian-Swedish national Ahmadreza Djalali, who was sentenced to death in November 2020, and 66-year-old Iranian-German Nahid Taghavi, who was arrested in October 2020 and has been placed in solitary confinement at the dreaded Evin prison in Tehran.

More recently, in the wake of the 2022 revolutionary protests, German Iranian Jamshid Sharmahd has been sentenced to death, with Germany reacting by expelling two diplomats from the Iranian Embassy in Berlin. More broadly, the regime responded to the protests with widespread repression, making nearly 20,000 arrests and killing more than 500 protesters. In addition, four protestors have so far been executed following sham trials and forced confessions, which U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk called “state-sanctioned killings.” Up to 100 more protestors face the same fate. The demand for the death penalty for demonstrators was supported by the overwhelming majority of the parliament (227 out of 290 members of parliament) – further evidence of the blurred lines between branches of government. In addition, there have been massacres in the Kurdish and Baluch regions of Iran.Corruption and the violation of laws are widespread among the political elite. However, people are rarely prosecuted, and, when they are, it is mainly a result of political rivalry. Within both the hard-line and the so-called reformist camps, a complex and powerful system of mafia-like family relations exists, most notably the Larijanis, Rafsanjanis, Khameneis, Khomeinis and Fereydoun (the latter being the clan of Rouhani and his brothers). Members of these families have held important public offices for several decades.

The report, which also deals with other aspects of the current situation in Iran, concludes with a strategic outlook:

The trajectory of Iran’s future depends primarily on two factors. Internally, questions loom about the fate of the ongoing revolutionary process that began in September 2022 and the impending succession of the supreme leader. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, born in 1931, will soon need to designate a new leader for the revolution. Presently, no clear successor is in sight. The prospects for fundamental revisions to Iran’s social, economic and foreign policies appear unlikely in a post-Khamenei Iran. The IRGC is best positioned to extend its dominance across all spheres, potentially shifting the regime’s ideological mix from Islamism to nationalism. Additionally, all three branches of power – the executive, legislature and judiciary – have been monopolized by conservatives or hard-liners, yet this has not translated into policies that benefit Iranian society or address pressing socioeconomic issues. Such an outcome could further deepen the public’s disillusionment with the entire political system.

On the international front, the Biden administration’s willingness to revive the nuclear deal has led to a more assertive stance from Tehran, demanding concessions that exceed the original 2015 JCPOA. This undermined hopes for a revived deal even before the fall 2022 protests, which made it politically costly for the West to engage Iran, began. Tehran’s intransigence has been fueled by its perception of Western weakness and a lack of a Plan B beyond reviving the JCPOA. With U.S. presidential elections approaching in fall 2024, Tehran has little incentive to fully commit to JCPOA’s nuclear obligations, fearing that a Republican successor to Biden might withdraw the United States from a renewed deal. As a result, Iran may not expect tangible or sustainable economic benefits from a new agreement. Furthermore, Iran’s nuclear escalation and the limited likelihood of revising the JCPOA have heightened the possibility of Israeli sabotage of or military strikes against Iranian nuclear facilities. This situation could potentially usher in a new era of regional tensions.

Despite Iran’s long-term agreements with non-Western great powers, such as a 25-year deal with China signed in March 2021 and a planned 20-year agreement with Russia, the economic benefits have fallen short of expectations. These agreements, marked by their lack of transparency, have raised concerns that Iran may have compromised national interests and resources to gain support from Beijing and Moscow, given the domestic and international pressures challenging regime stability. It remains uncertain whether Iran’s partnerships with Russia and China will evolve into strategic alliances, as Iranian propaganda suggests. Meanwhile, Iran’s key allies, which include Lebanon’s Hezbollah and the Assad regime in Syria, cannot compensate for the absence of strategic alliances.

Domestically, the regime has increasingly relied on brute force, as the country appears to be immersed in a revolutionary process for the foreseeable future. This process is driven by deep-seated economic and political grievances, as well as the state’s inability to address society’s basic needs, which has resulted in a growing and possibly irreversible gap emerging between the regime and society.

In summary, the prospects for political and economic reform in Iran appear bleak and are unlikely to materialize without internal and external pressure, regardless of who becomes the next supreme leader.