By Ahmad Rafat

Hamid Nouri, a former Iranian official, was convicted of war crimes and murder in May 2022 by a Swedish court. The court held 93 hearings before delivering the verdict. Nouri was sentenced to life imprisonment. In December 2023, the Svea Court of Appeal upheld his life sentence.

Despite these circumstances, Nouri was released and returned to Tehran on June 15 as part of a prisoner exchange deal.

ANALYSIS: Hamid Nouri’s Life Sentence Is A Condemnation of Iran

Simultaneously, Yohan Floderus, a Swedish diplomat and European Union official, and Saeed Azizi, an Iranian-Swedish citizen, were released from Iranian prisons and returned to Stockholm. Oman brokered the exchange deal, as it has done in previous cases.

The Iranian hostage trade — which began on Nov. 4, 1979 with the seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran by Iranian students, and the detention of 52 American diplomats and citizens for 444 days — has been a central part of the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy.

The release of 52 American hostages was a significant aspect of the Iran-Contra Affair, a political scandal which erupted during President Ronald Reagan’s second term. It involved the U.S. engaging in covert arms trade with Iran, despite Iran being under embargo, and the redirection of the funds towards the financing of the Contra rebels in Nicaragua, who were also under embargo.

Iran has a history of engaging in prisoner swaps, whereby it releases detained foreign nationals and Iranians with dual citizenship in exchange for concessions — including financial compensation, weapons, or the release of Islamic Republic agents. These exchanges often involve individuals who have been afforded due process by foreign courts and tried and convicted of crimes, including terrorism, espionage, and money laundering. However, they have returned to Iran after a short imprisonment.

The swiftness of the exchange of Nouri — accused of involvement in the mass execution of Iranian political dissidents — for Swedish nationals held hostage in Iranian prisons surprised many observers, despite the predictability of the event.

Nouri, who reportedly acted under the pseudonym Hamid Abbasi in the Gohardasht Prison in Karaj west of Tehran, was accused of being a member of a “death committee” that included a panel of three judges — including the late Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi – responsible for issuing death sentences in 1988 to many dissidents who were serving prison terms already.

The Islamic Republic’s eagerness to return Nouri to Iran is likely related to the presidential election planned for June 28 to find a replacement for Raisi, who died in a helicopter crash on May 19, which some people suspect was not an accident. Raisi’s Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian and six others also lost their lives in the crash.

Sources in Iran have said that the Iranian public is not enthusiastic about the election and that a majority of the electorate is unlikely to accept the results.

The Islamic Republic intends to portray Nouri’s release as a demonstration of its “diplomatic strength.” This narrative aims to convince the Iranian public that the government is capable of compelling Western countries to yield to its demands. The goal is to reinforce a perception of the current system’s stability and discourage potential boycotts of upcoming elections. By highlighting this perceived success, the government hopes to convey that a different future or regime change in Iran is not a priority for the international community.

ANALYSIS: How Hostage Taking Is An Integral Part of Iran’s Foreign Policy

The recent elections for the Majlis (Iranian Parliament) and the Assembly of Experts, held on March 1, saw a historically low turnout of eligible voters. According to official reports, only 40 percent of eligible voters went to the polls, the lowest turnout since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979. Independent sources suggest that the turnout may have been lower than 20 percent.

The low turnout in recent elections shows a growing disillusionment among Iranians as to their ability to influence government policies and behavior through electoral processes.

While Sweden was able to return two of its citizens by handing Nouri over to Iran, another three Swedish nationals remain in Iranian prisons. Nouri’s release was probably not valuable enough for the Islamic Republic to free all Swedish prisoners.

One of the three people who remain in prison is Ahmad Reza Jalali, an Iranian-Swedish disaster doctor, lecturer, and researcher who has been in Tehran’s Evin prison for 3,000 days and has been sentenced to death.

When Vida Mehrnia, Jalili’s wife, asked Sweden’s Prime Minister Ulf Hjalmar Kristersson about her husband’s plight, Kristersson did not explain why Iran was unwilling to discuss Jalili’s release. In 2016, the Tehran and Shiraz universities invited Jalili to Iran to attend several conferences.

In another case, a French citizen, Louis Arnaud, returned to France after Oman brokered his release. He had been arrested 20 months earlier on charges of supporting widespread protests in Iran and sentenced to 5 years in prison. In exchange for his release, the French government has agreed to deport Bashir Biazar, a former employee of the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) and an alleged Iranian intelligence agent. Biazar is currently under administrative detention in France.

Currently, three other French citizens are also in prison in Iran, and may be released through another deal.

A French teacher, Cecile Kohler, and her partner, Jacques Paris, were among several Europeans arrested in Iran on May 7, 2022. Another French national, Olivier, whose last name has not been released, was also arrested on unspecified charges.

The exchange of Asadollah Asadi, an Iranian diplomat convicted of terrorism, for Belgian aid worker Olivier Vandecasteele in 2023, was a highly controversial event. Asadi was convicted in Belgium in 2018 for his alleged role in a foiled bombing plot targeting a rally of Iranian opposition groups in France in 2018. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Vandecasteele was arrested in Iran in 2022 and sentenced to 40 years in prison on charges of espionage and undermining national security. In January 2023, Belgium and Iran agreed to a prisoner exchange. Asadi was released from prison in Belgium and returned to Iran in exchange for the release of Vandecasteele. Another Belgian aid worker, an Iranian-Austrian business executive, Massoud Mosaheb, and a Danish Blogger, Thomas Kjems, were released by Iran.

The UK and U.S. governments have made significant payments to the Islamic Republic of Iran in exchange for the release of their nationals.

In March 2022, the UK government paid $520 million to Iran for the release of British-Iranians Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Anoosheh Ashoori. In August of the same year, the U.S. government released $7 billion of the Islamic Republic’s frozen assets in South Korea for the release of Mohammad Bagher Namazi.

During Barack Obama’s presidency in 2016, the U.S. government sent $1.7 billion in cash to Iran in a plane for the release of Jason Rezaian, an Iranian-American journalist, and three other dual nationals: Saeed Abedini, Amir Mirzaei Hekmati, and Nosratollah Khosravi.

The Italian and Spanish governments have not disclosed the exact amount of money they paid Iran for the release of Italian blogger Alessia Piperno and former Spanish soldier and world traveler Santiago Sanchez Cojedor, who were arrested in Iran in 2022. They were respectively accused of participating in protests and visiting the grave of Mahsa (Zhina) Amini in Saqqez.

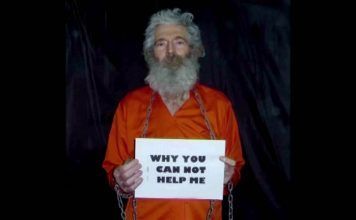

The Islamic Republic of Iran has arrested at least 173 foreign nationals and dual citizens since its establishment in 1979.

There are currently at least 29 hostages in Iranian prisons, 20 of whom are citizens of Western countries or Iranians with dual citizenship. The names of some of these people are not known, such as six people who are accused of espionage or four people who are accused of Satanism.

Among the well-known names in prison are Nahid Taghavi and Jamshid Sharmahd, both German citizens; Mehran Raouf, Shahram Namavar, and Nasrin Roshan, British-Iranian; Shahab Jalili, a dual Iranian-American citizen; and Serin Badie, a New Zealand citizen.

In November 2020, Kylie Moore-Gilbert, an Australian-British academic specializing in Middle Eastern political science, was released by Iran after spending 804 days in Tehran’s Evin and Gharchak prisons. Her release followed the release of three Iranian nationals, who were imprisoned in Thailand on charges of planning to bomb the Israeli embassy in Bangkok.

In June 2019, French sociologist Roland Marchal and his partner Fariba Adelkhah, an Iranian-French dual citizen, were arrested during a visit to Iran. Marchal was detained on charges of “collaborating with a hostile government” and was held in Evin Prison.

Marchal was released in a prisoner swap between France and Iran the following March. In exchange for Marchal’s release, France returned Jalal Rouhnejad, an Iranian engineer who was arrested in Paris on security charges.

However, Adelkhah was released in September 2023.

In 2019, an American-Chinese researcher, Xiyue Wang, was exchanged for Massoud Soleimani, who had been arrested on espionage charges by the U.S. authorities. Wang was a doctoral student at Princeton University, researching the Qajar dynasty for his history degree. He was arrested in Iran in August 2016 and sentenced to 10 years in prison for “espionage” by an Iranian court.

Soleimani was an Iranian scientist and professor who was arrested by the U.S. authorities in October 2018 upon arrival at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport, accused of violating sanctions by attempting to export biological materials without obtaining permission from the U.S.

There are many Iranian officials and prominent figures who blatantly admit that taking foreign nationals and Iranians with dual citizenship as hostages is a way to solve Iran’s political and financial problems.

In a speech in January 2020, Hassan Abbasi, an Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) officer and conspiracy theorist who heads the right-wing think tank the “Center for Borderless Security Doctrinal Analysis,” said: “We capture a spy (Jason Rezaian) and in exchange for his release Iran received $700 million from the U.S.”

“The IRGC gets $1.7 billion for one spy,” Abbasi noted in his speech titled Ways to Generate Revenue for the IRGC. “Therefore, by capturing one spy, the IRGC generates nearly $2 billion, which is what the government has allocated to the force in its budget,” Abbasi added.

During a TV interview, Mohsen Rezaei, a former IRGC commander and a current member of the Expediency Council and the secretary of President Raisi’s “Economic HQ,” said: “As a soldier and a guardian of the revolution, I promise that if the U.S. holds any bad intention towards Iran and plans a military attack on the country, we would capture at least a thousand Americans in the first week, and then they will have to pay several billion dollars to free each of them. Then our economic problem may also be solved.”