- This piece was submitted to Kayhan Life by Lawdan Bazargan: a former political prisoner, human rights advocate, and relative of victims of the 1988 massacre of political prisoners in Iran. The views expressed are her own.

By Lawdan Bazargan

When I heard the news of the terrorist attack against Salman Rushdie, the British-American author, I was shocked and perplexed. Thirty-three years after his death, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini continued to spread hatred and division.

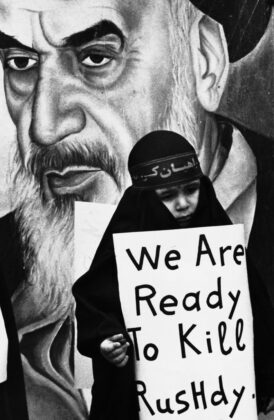

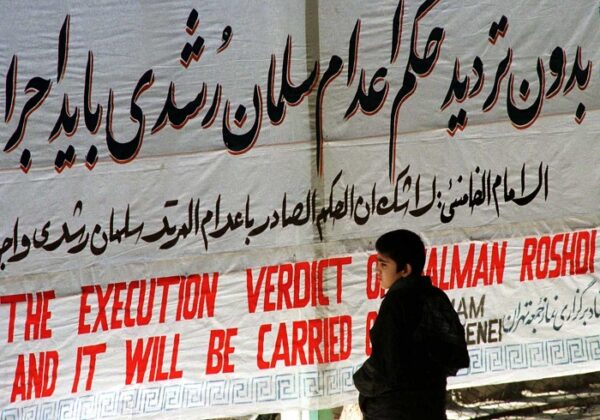

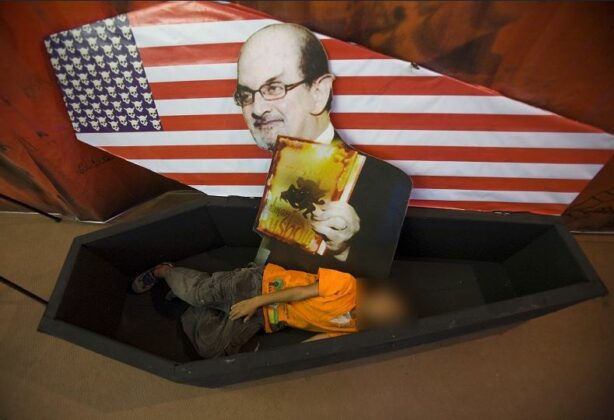

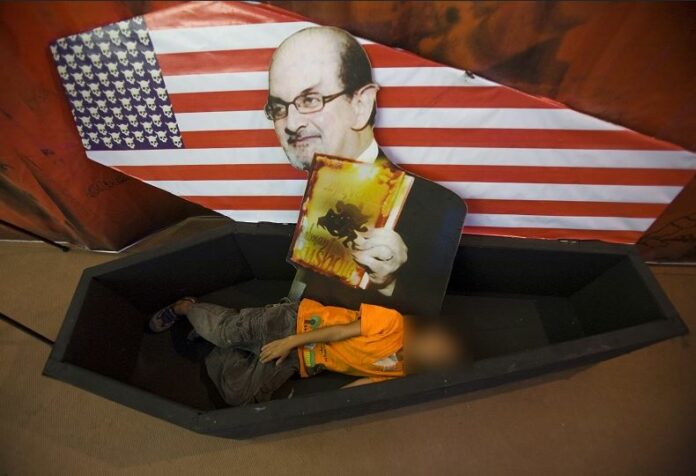

In 1989, Khomeini, the Supreme Leader of Iran, issued a fatwa, or Islamic edict, against Mr. Rushdie for his book “The Satanic Verses,” blaming its critical and offensive tone toward the Prophet Muhammad and other aspects of Islam. In his fatwa, Khomeini sentenced the author and all editors and publishers associated with its contents to death.

Instead of denouncing this direct attack on free speech, many Muslim leaders and even moderate Muslim cultural figures condemned Rushdie or stated that he had gone too far. The punishment for apostasy in Islam is death.

Many booksellers refused to sell Rushdie’s book for fear of retribution. A number of bookstores that did sell “The Satanic Verses” were bombed, the novel’s Japanese translator was stabbed to death, and an its Italian translator critically wounded by an assailant. Dozens of people were killed or injured in protests against the book which have been described as “one of the deadliest—and possibly the most widespread—instances of conflict between religious fundamentalists and free-speech activists of the 20th century.“

While Rushdie was in the emergency room fighting for his life, many said that they would pray for him. But I couldn’t. I stopped praying at the age of 12 when Khomeini’s regime killed my 17-year-old cousin. My cousin had been injured by a bullet at age 14 while protesting against the Shah’s regime. Less than three years later, he was arrested in a protest against Khomeini’s regime, the same regime that he had helped to bring to power.

I still remember the screams and cries of my mother when my aunt called and said her son was missing. They started going to morgues and hospitals, thinking he might have been in an accident, but they could not find him. I started praying with all my might. I had never lost anyone before and wanted my cousin to be alive.

Fourteen days later, Iranian newspapers reported, “Today 73 armed terrorists were executed in Tehran.” My cousin’s name was among them. I decided then that a God that does not listen to the prayers of a child and allows a teenager to be executed does not deserve my admiration and love.

While I desperately awaited news of Rushdie’s health, I remembered the time when my brother went missing. My brother Bijan Bazargan, a college student, was arrested about a year after my cousin’s execution for his leftist views, and received a 10-year sentence. When Bijan’s visitations were stopped in the summer of 1988, he had already spent more than six years behind bars. All political prisoners’ visitations were stopped, and the authorities were giving families no straight answers. My parents were desperately going to prison, to court houses, and to the justice department, but the authorities would only tell them: “Go home and wait for our call.”

Soon the authorities started telling some families that their son or daughter had been executed. Then we learned that some of my brother’s cellmates were among the dead. We started going to the memorials that the families would hold in their homes, since the Islamic Republic had prohibited public mourning and refused to tell families where their loved ones had been buried.

I was 19 then, and witnessing the desperate cries and laments of the deceased’s family members. I hoped with all my might that this would be the last life that the Grim Reaper would take away from us. It was a vain hope.

The next day, we received the news of the execution of a few more. I had experienced the Islamic Republic of Iran’s prisons. I knew that if all of these people were dead, for Bijan to be alive, he must have had to accept all the conditions — meaning repent and accept the regime’s ideology. Knowing Bijan, I knew that this scenario was worse to him than death, but at least I held the hope that he was alive and breathing.

That bubble burst after five months, and we were finally told that Bijan was executed too. The last beam of light was gone, and we were left in complete darkness.

Another fatwa by Khomeini condemned Bijan and thousands of other political prisoners to death, accusing them of “waging war on God.” Prisoners were summoned in front of four-member inquisition panels, later called “Death Commissions.” The panel lasted only minutes. Prisoners were asked a few short questions about their personal beliefs. The wrong answer would send them to the gallows to be hanged immediately. When Bijan was asked, “Do you believe in God? Do you believe in Islam? Do you believe in Khomeini?” he responded, “I don’t answer these Inquisition-like questions,” knowing that the punishment was death.

My brother and thousands of others died defending their beliefs and right to free speech, while the people who helped Khomeini spread his message of hate and division are now living and teaching at Western universities.

I am delighted that Mr. Rushdie survived the attack. I wish Bijan and other prisoners were as lucky and miraculously saved. I hope that once he has completely recovered, Mr. Rushdie, a gifted storyteller, writes their stories and commemorates the young men and women whose destinies are enmeshed with his own.

ANALYSIS: Rushdie Attack Highlights Ongoing Persecution of Authors in Iran

Safety Concerns Loom as Writers Show Public Support for Rushdie