Child sexual abuse is at an all time high in both Iran and the UK, but how does each country treat offending paedophiles, and are they really that different?

The UK’s child sex abuse epidemic is, by now, well documented. Whilst a dedicated national inquiry looking into the prevalence of non recent abuse, probes government bodies and religious institutions about the parts they played in enabling abuse over a series of decades, recent figures show an alarming rise in the number of children being sexually and emotionally abused. In the last year alone, reported cases of child sex abuse rose by 31%, at a time when sexual assault cases involving children inside the country are at record levels.

Iran, despite its opaque criminal justice system and reluctance to share its problems with the outside world, has been unable to contain its own child abuse epidemic. The scandal has spilled out, beyond the country’s geographical borders, onto the internet, where Iranian children have begun to use social media platforms to engage with the #MeToo movement, sharing their own personal experiences of being abused.

On the surface, the UK’s accessible laws and guidelines on child sex offences, and its carefully crafted policies which promote children’s rights and seek to protect them, seem completely at odds with the Iranian government’s approach. Iran has still not ratified its Children’s Rights Bill, which was produced in 1995 with the hope of protecting children and preventing abuse. The Bill found its way back into the spotlight in 2018, after Mohammad Kazemi, MP for Malayer, a city in Western Iran, suggested that the details of the Bill were being fleshed out and would be finished by 19th February of this year. The Bill has since vanished into obscurity.

Another piece of draft legislation, The Bill for the Protection of Children and Juveniles, was also promised, but has been stuck in limbo inside Iran’s Parliament since 2011, despite being submitted to the government in 2009.

Then there is the question of the death penalty. Arguably the greatest distinction between the two countries, the UK does not recognize the death penalty, whilst Iran is one of the world’s most prolific countries for executions. Under Sharia Law, child molestation is punishable by death.

This may seem like the defining difference between Iran and Britain, but the most impactful contrast lies in the Iranian court system’s lack of willingness to tackle child abuse in the first place. Though the exact number of orders for the death penalty in child molestation cases is not known, figures available suggest that these kinds of executions are virtually unheard of.

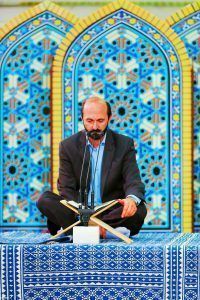

That’s not surprising for a country whose rulers openly condone paedophilia both within home and education settings. The recent case of a high profile Quran reciter, Saeed Toosi, who had his sentence overturned after being found guilty of sexually abusing teenage students, was marred by accusations that the Supreme Leader’s office was responsible for the acquittal. In 2016, a nine year old girl was sexually molested by a teacher. Despite clear medical evidence that she had been raped, the court refused to acknowledge the finding and chose to charge the man with the lesser offence of “illegitimate relations”. The family has since vowed to pursue legal action against the teacher, who is considered influential, after taking the view that the court ignored them because they were poor and without connections.

Perhaps the most telling case in this field, is one which takes us back to 2004. Atefeh Sahaaleh Rajabi was just sixteen when she was sentenced to death for having unlawful sex. An investigation by Amnesty International and the BBC, revealed that rather than engaging willingly in sexual activities, she suffered with psychological difficulties, and had been raped multiple times by a 51 year old man. Atafeh was hanged. The man was given 100 lashes.

Much like British courts did in the past, Iran’s current justice system continuously sidesteps the issue of child sexual exploitation, leaving abusers free to target children. The Child and Youth Protection Bill, which was enacted on 16 December 2002, covers only a small number of child abuse issues, and effectively legalizes paedophilia, by allowing fathers to marry their stepdaughters. Despite ratifying the UN Convention of the rights of the child (CRC) in 1994, the Islamic Republic of Iran implemented the Convention with a reservation, allowing it to ignore certain aspects of the law if it contradicted its own national and domestic legislation. The end result is that law enabling sex with minors, like the one contained in the Youth Protection Bill, sit legitimately alongside the Convention which was designed to prevent such abuses in the first place.

If Iran seems confused in its approach to paedophilia, or at least appears to be trying to strike a fictitious balance between what Islamic jurisprudence demands, the West expects, and what Iran’s government feels it is entitled to, then the UK’s stance on child abuse is just as self serving.

The idea that the rich and powerful can avoid prosecution in child sexual abuse cases is a phenomenon that will sound familiar to the British public. In the wake of the Jimmy Savile case, and ongoing allegations about VIP child abuse rings featuring Westminster politicians and peers, there’s a rising awareness about abuse hiding in plain sight, especially at the hands of high profile individuals. Whilst Iran’s ruling class has no appetite for addressing child abuse inside its court system, the UK’s government is also putting on the breaks, though perhaps for different reasons.

The sheer scale of abuse in the UK has brought its police, social work and court systems to their knees. Large scale investigations into non recent abuse stretching back to the 1940s, and dozens of probes looking into today’s grooming gangs and child traffickers in major towns and cities in the UK have left the police with little resources and even less time to carry out the full range of its duties. The social work sector in England has also been badly affected by the ever growing number of child abuse cases, and budget cuts which have left councils cash strapped and drained of staff.

In the wake of mounting pressure, strands of British government, much like Iran’s own governing bodies, have chosen to trivialize child sexual abuse in order to distance itself from it. Unlike Iran, the underlying driver for the UK government’s position stems around a need to protect its finances. Simon Bailey, the National Police Chiefs’ Council lead for child protection, issued a statement claiming that the way to handle the resource issues faced by the police was to ignore low level offending paedophiles accessing online child abuse images, and set them free. Bailey justified the move, telling the The Telegraph in 2017, that officers couldn’t cope with the number of reports they were receiving. He also told the newspaper that low level offenders could be placed on the sex offenders register and given counselling instead. The perspective ignored the reality of online child pornography: that those who watch and download it are feeding an industry which will keep running on a demand to exploit real children, and that the line between low level paedophiles and dangerous child sex offenders is, most of the time, blurred. The idea that the sex offenders register is a magical cure-all is also without merit. Convicted paedophiles placed on the register cannot be monitored at all times, and there have been instances where convicted paedophiles on the register have reoffended while out in the community.

If Iran has chosen not to address child sexual abuse because it’s leaders are unable to imagine a world where children are free from malignant patriarchal rights of ownership, then the UK has chosen to bury its head in the sand, and window dress its abuse problem instead.

A convicted paedophile in England caught with over 137,000 child sex abuse images, was spared jail in 2016 after telling the judge that he hoped to start a family. The judge agreed to wave a possible five year sentence, despite the police discovering an extra 4,336 videos, not all of which could be categorized due to the volume of material involved. The judge also took into account an early guilty plea and the man’s previously clean criminal record, despite the court being told that the man had spent four years accessing and downloading child abuse materials from the internet before eventually being caught. Another case in 2017, involving a paedophile who was found with over two million child abuse videos, caused an uproar in the UK when the judge felt he had no choice but to set aside the possibility of a prison term, after sentencing guidelines prevented him from putting together a suitable rehabilitation programme for the paedophile. Judges, campaigners and survivors of child abuse have all called out the government on its lenient sentencing of child abusers. A report published by Netclean found that 64% of organisations interviewed felt that laws around the world, including the UK’s, were not suitable for child sexual abuse crimes, either because they were outdated, or limited regarding the need for international cooperation. To this day, the UK still does not have a working definition for child abuse.

From ratifying human rights legislation with no intention of honoring its spirit, to the production of endless reports offering ways to end child abuse which remain ignored, both governments in Iran and the UK are guilty of making token gestures. Where the lives of children are at stake, trying to find an acceptable line inside either country whilst child abuse remains at critical levels is impossible, and ultimately unhelpful to those children who are still suffering at the hands of their abusers.

Natasha Phillips is Kayhan Life’s managing editor and writes pieces on humans rights and child rights in Iran.