May 16, 2017

By Ann Saphir

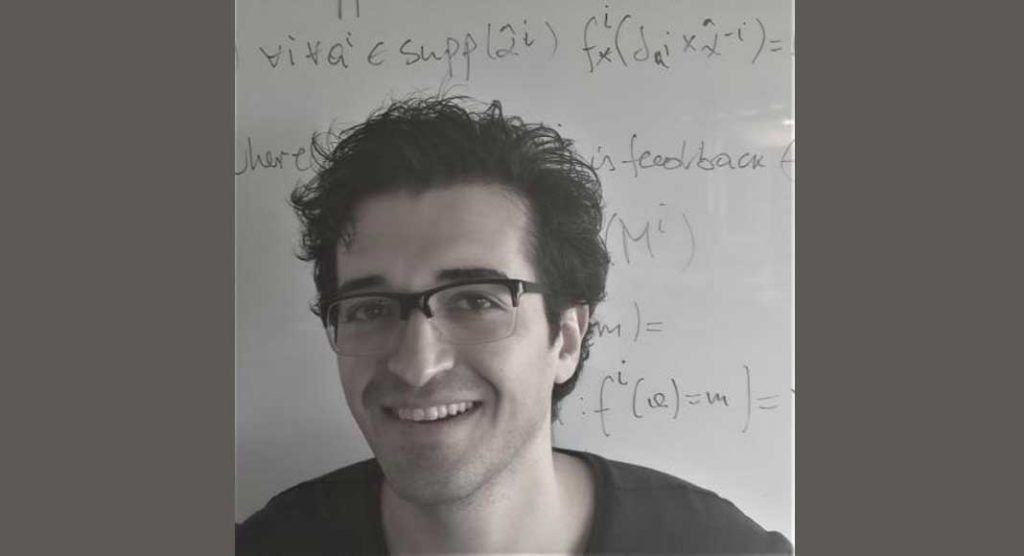

SAN FRANCISCO (Reuters) – Ramin Forouzandeh had applied to 13 PhD economics programs in the United States, but after President Donald Trump signed his first travel ban in January, the 25-year-old Iranian turned to Canada for other options.

He said he had focused on U.S. schools because they hosted most of the world’s top 20 economics programs. “Before the travel ban, I never really considered other alternatives.”

By late March, U.S. courts had halted two versions of Trump’s travel ban, yet Forouzandeh signed for University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management and turned down the University of Minnesota’s prestigious PhD program.

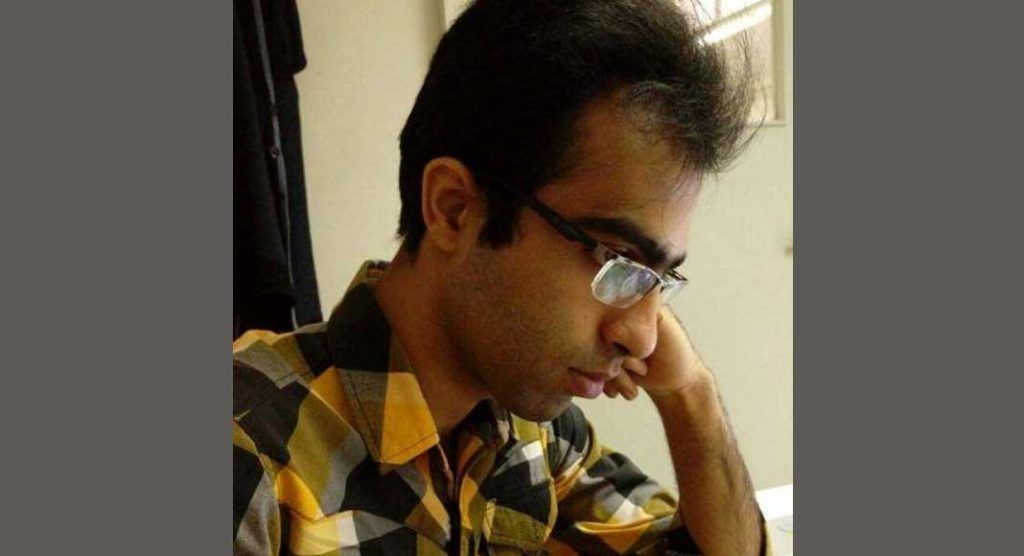

His countryman, Mahdi Ebrahimi Kahou, 30, was well into his first year of the Minnesota program when he decided to transfer to the University of British Columbia because of Trump’s executive orders that banned travel from seven and later six Muslim-majority countries, including Iran.

“I lost my motivation to work completely,” he said.

A Reuters survey of 19 Canadian universities showed a spike in international applications, most notably from Iran and India. Five top Canadian economics and business PhD programs are getting at least half of their new Iranian students this fall because of the ban, based on interviews with universities and students. Most of those, like Forouzandeh and Ebrahimi Kahou, are opting out of U.S. programs in a field where the United States both dominates and relies on foreign talent.

While those programs represent only one field and a fraction of the U.S. student population, they offer early evidence of the direct impact of Trump administration policies. Academics fear they may also be a sign of things to come if the chilling effect of Trump’s “America First” agenda spreads beyond any specific field of study or nationality.

BEST AND BRIGHTEST

“This strikes at the heart of what has made U.S. higher education the envy of the world,” said Mary Sue Coleman, chair of the Association of American Universities. “It’s this notion that the U.S. is no longer a welcoming place for the best and the brightest.”

Iranians are by far the biggest group among students directly affected by the bans and form a small but notable part of the talent pool in areas such as engineering and economics, where U.S. academic institutions excel. Iranians ranked sixth last year among international students enrolled in U.S. graduate programs, according to the Institute of International Education.

A survey conducted jointly by five U.S. higher education associations in February showed 38 percent of U.S. colleges reporting a drop in foreign applications, with those from the Middle East down the most, while 27 percent saw no change – a significant cool-down after nearly a decade of steady growth.

In 2015, at least 35 percent of graduate students at U.S. universities granting graduate degrees in science, engineering and health were foreigners, according to the National Science Foundation.

This year, about 60 percent of graduating PhDs from the top 10 U.S. economics departments come from other countries, a Reuters analysis shows.

“You’ve got an issued order that’s been temporarily blocked that applies to six countries. But the destabilization of the whole situation for international students and faculty could not be overstated,” said Rice University President David Leebron.

He said that for foreign students everything from getting a visa on time to employment opportunities had been thrown into question.

According to Rice’s dean of graduate and postdoctoral studies, this year’s PhD programs will have slightly fewer Chinese, Indian and Middle Eastern students than expected. More Iranian students declined offers of admission than usual, with several saying that they decided to study in another country because of concerns about getting a U.S. visa.

There is no evidence of a mass exodus of foreigners – indeed, Rice will have more students than expected from Europe and Latin America, offsetting declines elsewhere – but academics cite dozens of examples where Trump’s policies had an impact.

At Arizona State University, for example, Iranians would typically make up a fourth of the economics PhD program, but there will be none in the incoming class this fall. Of those already enrolled, two are moving to Canada. One student who visited his family in Iran over the Christmas break still has not been able to return, leaving the university scrambling to cover the classes he was supposed to teach.

“The effects of this are big,” said Gustavo Ventura, ASU’s economics department chair. “These people, not just the ones that come to us – anyone who comes to a PhD program abroad – are the cream of their student population.”

The University of Illinois now has 10 Iranians in its PhD program, and while it’s not certain why, none of the Iranians whom it offered admission are among the 22 students from 11 countries entering in the fall.

At Indiana University’s economics program, three Iranians withdrew their applications almost immediately after the travel ban, said Todd Walker, director of the department’s graduate studies.

“We also had many more international applicants turn us down this year relative to the last three years,” he said. “I cannot say definitively how much of this is attributable to the travel ban, but I suspect it played a role.”

In British Columbia, the Simon Fraser University has admitted 20 percent more international students for the fall term, according to Associate Dean Jeff Derksen. He said queries he had received and an online survey suggested more graduate students were considering alternatives to U.S. programs.

“This indicates that the international map of academic knowledge production has changed.”

The prestige of the U.S. programs remains a big draw, but those committed to a U.S. career are more aware of risks.

For example, Soheil Ghili, who is getting a PhD in economics from Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management this month and will start as a post-doctoral fellow at Yale this summer, is hedging his bets.

“Let me put it this way: I will be more careful to not miss networking opportunities with people from Toronto and London.”

(With reporting by Solarina Ho and Alastair Sharp in Toronto and Yeganeh Torbati in Washington; Editing by Peter Henderson and Tomasz Janowski)