January 10, 2017

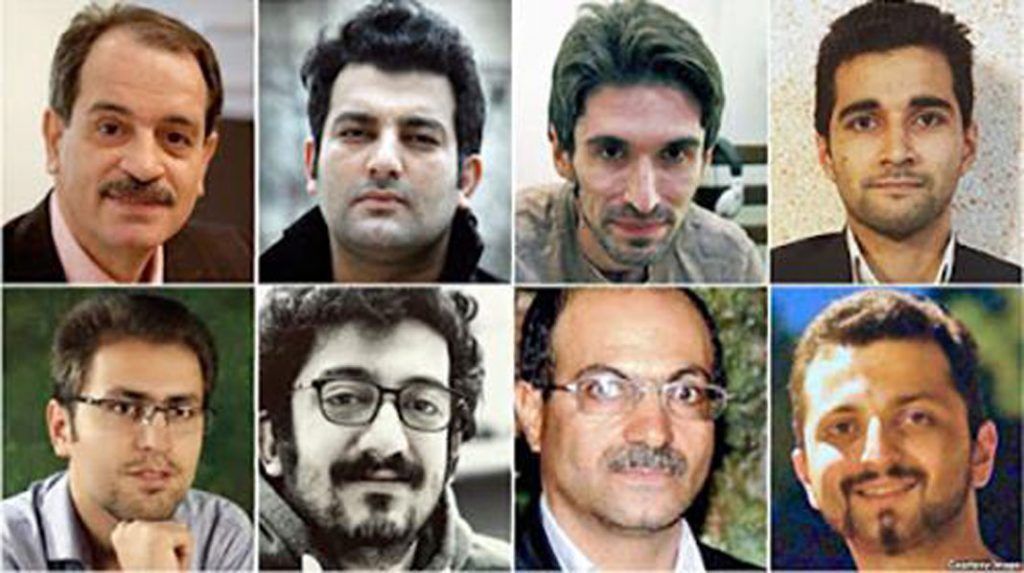

Arash Sadeqi, a human rights activist, ended his hunger strike after seventy- one days on 3 January, 2017. Iranian authorities had temporarily released his wife, Golrokh Ebrahimi-Iraee, who had been sentenced to six years in prison for insulting Islamic sanctities. Sadeqi was sent to jail for nineteen years in 2015 on the charge of “acting against national security, spreading lies in cyberspace, and insulting the founder of the Islamic republic”. Two other jailed activists, Morteza Moradpour and Hossein Rastegari-Majid, also ended their hunger strikes recently, after 65 and 35 days, respectively.

Meanwhile, a number of other prisoners of conscience continue their hunger strike, including Ali Shariati, Saeed Shirzad, Zartosht Ahmadi-Ragheb, Ayatollah Mohammad Reza-Nekounam, Mehdi Koukhian, Ahmad Reza Jalali, and Mohammad Saber-Malekraeisi.

Hunger strike is a political protest of last resort staged by activists who risk death to draw public’s attention to their cause and to force authorities to meet their demands. Akbar Mohammadi and Hoda Saber are two political prisoners who starved themselves to death in the custody of the Islamic republic.

Recent reports about the deteriorating health of Sadeqi and Shariati received worldwide attention, with many people tweeting their support for the two men. Their predicament became the top trending story for a few hours on social media networks, even though the Iranian security forces dismissed the flood of Twitter support by claiming that the entire event was fabricated through the use of various Telegram channels.

Despite the best efforts of the Islamic republic’s authorities to defuse the crisis, the world has now heard the silent cries of the imprisoned activists currently on hunger strike. Amnesty International, a large number of British MPs, and Madrid City Council are among a group of world bodies that have expressed concern over the welfare of political prisoners in Iran.

As effective as social media have been in raising concerns about the treatment of political prisoners, it was the social activists and prominent figures inside Iran who ultimately forced the authorities to deal with the issue. In a rare show of restraint, security forces neither banned nor disrupted a peaceful protest in front of Tehran’s notorious Evin prison that was held in support of Sadeqi.

There have been a number of other peaceful demonstrations in Tehran in recent days, including one by the students of Mohammad Ali Taheri, a researcher in alternative medicine and the founder of the “Mystical Ring”, who showed up en masse at Evin to protest his incarceration.

Iranian politicians have also heard the public’s outcry. A number of Majlis (Iranian Parliament) deputies recently met with officials from the Judiciary to discuss the mistreatment of jailed activists. Reformist deputies within the “Hope Fraction,” pro-Rouhani parliamentarians, believe that the hunger strikes could damage the regime. They are clearly concerned about the May 2017 presidential elections. To muster up votes, various political factions have in the past championed certain popular causes close to election time, but dropped them as soon as the elections were over.

Support for those on hunger strike has not been broad and unequivocal but rather selective and partisan in nature. A number of politicians in the reformist camp have championed the plight of Shariati who had been a key member of President Rouhani’s campaign headquarters in Isfahan.

Golrokh Ebrahimi-Iraee, on the other hand, has been branded a terrorist, not only by the security agencies and hardliners, but also by the so-called “Prudence and Hope” government of President Rouhani. Her support for Shahram Ahmadi, a Sunni Kurdish activist who was recently executed, and Zeynab Jalalian a member of PJAK (Kurdistan Free Life Party), who is currently serving a life sentence, will not bring her mercy in the Islamic republic. Conspicuously, the name of Morteza Moradpour, an Azeri rights activist, was missing from the list of those whose health and well being had been a concern for the protesters.

As effective a tool hunger strike is in achieving political objectives, the cases of Moradpour, Sadeqi, and Rastegari demonstrate the limits of such tactics. Reza Khandan, husband of human rights lawyer and former prisoner of conscience, Nasrin Sotoudeh, warned on his Facebook posting: “ Authorities push a prisoner on hunger strike to the brink of death before agreeing to the demands, but once the individual has ended the hunger strike, they renege on their promises.” Highlighting Sotoudeh’s peaceful protest after the authorities imposed a travel ban on her daughter, Mehraveh Khandan, she wrote that “ she ended her hunger strike after 49 days following a short visit from a number of Majlis deputies who assured her of lifting the travel ban on Mehraveh. However, the travel ban has not been lifted.”

There are no guarantees that Ebrahimi-Iraee, who is on a temporary release and Moradpour, who is currently hospitalized, will not be sent back to prison once the protesters have gone home and the fate of the activists becomes yesterday’s news. Experience has shown that only unrelenting resistance and persistent protest could safeguard the human rights of Iranian citizens. The recent wave of hunger strikes is irrefutable proof that public support and pressure from the international community enables the prisoners to force their demands on the authorities of the Islamic regime.