February 19, 2017

Peyman Pejman

Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, in the United States, the topic of radicalization of mostly young men in the Islamic world has become a top political topic. I italicized “political” because, essentially, it has been the perimeter within which the topic has been discussed, both in political terms and often for political reasons, by mostly, but not exclusively, politicians.

While many commentators, analysts, and journalists knowledgeable about the Middle East, like Thomas Friedman of the New York Times, have called for “reformation” within Islam, as well as fundamental re-examining and restructuring of the educational and labor market conditions so the uneducated and lower-class youth can feel more hopeful about their future, those calls have traditionally come from the West.

And that orientation and source of such calls has been one of the problems. It has widened the “Us v. Them” arguments, and made what otherwise would have been very legitimate discussions less appealing yet valid in a culture, and in a part of the world fiercely proud and protective of its religion and cultural values.

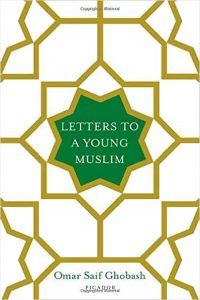

Now, critics and genuine good-doers in the West might have met their match in Omar Seif Ghobash, the author of Letters to a Young Muslim. Currently, the ambassador to the Russian Federation representing the United Arab Emirates (UAE), arguably the most progressive and forward-looking country in the Middle East, Ghobash brings the kind of solid thinking and gravitas to the argument that few in the West could afford, if for no other reason than the fact that he is from “their” side, and has the educational and political clout that few others do.

Ghobash’s approach to the book is interesting in that he does not “lecture” why radicalization is bad. He breaks it down into why it happens and then builds the arguments back up.

“Initially, I thought I wanted to speak to myself and to my children,” Ghobash told Kayhan London. “The questions I ask are the questions I asked when I was 15 and I think they are universal questions in all societies and I feel very strongly that we, in the Arab world and the Muslim world, should not be afraid of these questions because there are ways of answering these questions which are not heretical or threatening our belief system.”

The book can be appealing because, in some unconventional ways, many young Muslims on the verge of radicalization, might actually connect with Ghobash’s own background. He was born to a Russian mother and an educated technocrat father he lost at an early age to random political assassination, leaving him with no male role model. He, too, initially did not fit into the Arab society. He barely spoke Arabic, was brought up in boarding schools in Europe, and was utterly out of place when he returned to the UAE. He worked on his Arabic, became disenchanted with the society around him, took refuge in Islamic teachings, and for a while, totally isolated himself from “friends” he did not consider “good Muslims.” In other words, pretty much like how many young Muslim men feel before they jump off the proverbial cliff and formally join groups such as ISIS, Taliban, or Al Qaeda.

The book can be appealing because, in some unconventional ways, many young Muslims on the verge of radicalization, might actually connect with Ghobash’s own background. He was born to a Russian mother and an educated technocrat father he lost at an early age to random political assassination, leaving him with no male role model. He, too, initially did not fit into the Arab society. He barely spoke Arabic, was brought up in boarding schools in Europe, and was utterly out of place when he returned to the UAE. He worked on his Arabic, became disenchanted with the society around him, took refuge in Islamic teachings, and for a while, totally isolated himself from “friends” he did not consider “good Muslims.” In other words, pretty much like how many young Muslim men feel before they jump off the proverbial cliff and formally join groups such as ISIS, Taliban, or Al Qaeda.

At that point in life, he writes in the book, “You find that it is difficult to be a Muslim and live in societies that are seen to be made up of lonely, sullen, and isolated individuals … It is difficult to accept the mundaneness of the world you live in … You might compensate by looking at some of the Muslim website” run or supported by more-extreme religious scholars.

That gradual approach towards some of the more radical religious teachings puts the responsibility squarely where many think it should rest.

Ghobash argues that he is not trying to pick a fight with religious scholars, emphasizing that he believes in “personal responsibility of individuals,” but he does not absolve those scholars of their responsibility either.

“When I talk about closed-minded clerics, I am not picking on any particular group to say, ‘You are the problem.’ In fact, I think clerics are as much the partners in the future of Islam,” he told Kayhan London.

“Where I think some of them have not quite made the jump is to really understand that if you are interested in the greater ethical meaning for the lives of people in the Middle East and the Islamic world, they need to make the effort in not just understanding the 7th, 10th, and 14th centuries, they also need to understand how life has changed for the ordinary Muslim.

“Still, I hear in some of the sermons of some leading clerics that they talk about the ‘non-specialist’ as sheep to be led, to be told, to be educated, to be instructed. I think that’s simply out of date and there is no harm in admitting that it is out of date, and to engage in a more equal conversation.”

That “equal conversation,” Ghobash says, must include what many in the Islamic world consider taboo subjects, those that cannot be discussed, let alone questioned; questions such as sex, homosexuality, education for girls, or co-mingling in the workforce.

“The binary world is not the only Islamic world you can live in. There is much more gray in between the black and the white that the ulema and other scholars present us,” he writes in the book. “The gray is where you develop intellectually and morally.”

Neither does Ghobash. Despite his fierce loyalty to his country and the ruling UAE royal family, he gibes a pass to governments, his included, in not having done better to improve the economic lot of young Muslims around the world.

“The unfortunate reality for the rest of the world is that today’s Arab youth will shape the character of the region over the coming years. This could mean that we witness more anger and destruction, or productivity and progress, or a return to the traditional institutions of Arab and Islamic culture,” he writes in the book.

“Rigid job markets, out-of-date legislation, sectarianism, a weak productive identity, and finally, the oil price collapse that created a regional deficit of 9 percent of the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) in 2015, after years of surplus productivity are the extreme disadvantages troubling our youth.”

Despite, or perhaps because of his layered analysis of roots of radicalization, and ways to deal with them, Ghobash does not suggest that heeding his ideas would put groups such as Taliban or ISIS out of business.

“The problem with groups like Al Qaeda, and maybe ISIS, is that they consist of military people looking for a new job. These are people who spent time in Afghanistan and then what do you do with them, what do they do with themselves? They are committed to a lifestyle and it has its own dynamics. I doubt they believe every single day this is a fantastic choice,” he told Kayhan London.

The way this book has been written and published is also interesting, and it is a testimony to the open intellectual culture of the UAE that makes it distinguishable, not only from other Arab and Gulf states, but also from many Western countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom.

It is almost universal practice that senior government officials must submit books, or often lectures or any other material to be printed, first to be vetted by some government reviewing authority. In this case, Ghobash said he had absolute freedom throughout the process of writing, publishing, and promoting the book.

“I assumed that I had to do that. That’s why I went to my boss and members of the royal family in Abu Dhabi and asked specifically for permission to write a book. Permission was granted immediately, without further question, as to what I was going to write about … At no stage did anyone ask me for a copy to verify what was in it,’” he told Kayhan London.

“I have been very lucky. Maybe I said something so very inoffensive and not interesting that it did not offend anybody,” exclaimed Ghobash!!

*Views expressed in this article are the writer’s alone and not necessarily those of this publication. The book is being translated into Arabic, German, Turkish, and Mandarin.