September 29, 2016

Two major Iranian banks refused to work with companies affiliated with Khatam-al-Anbiya, the engineering wing of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) recently. Bank Mellat and Sepah Bank both cited international sanctions against the companies as rationale.

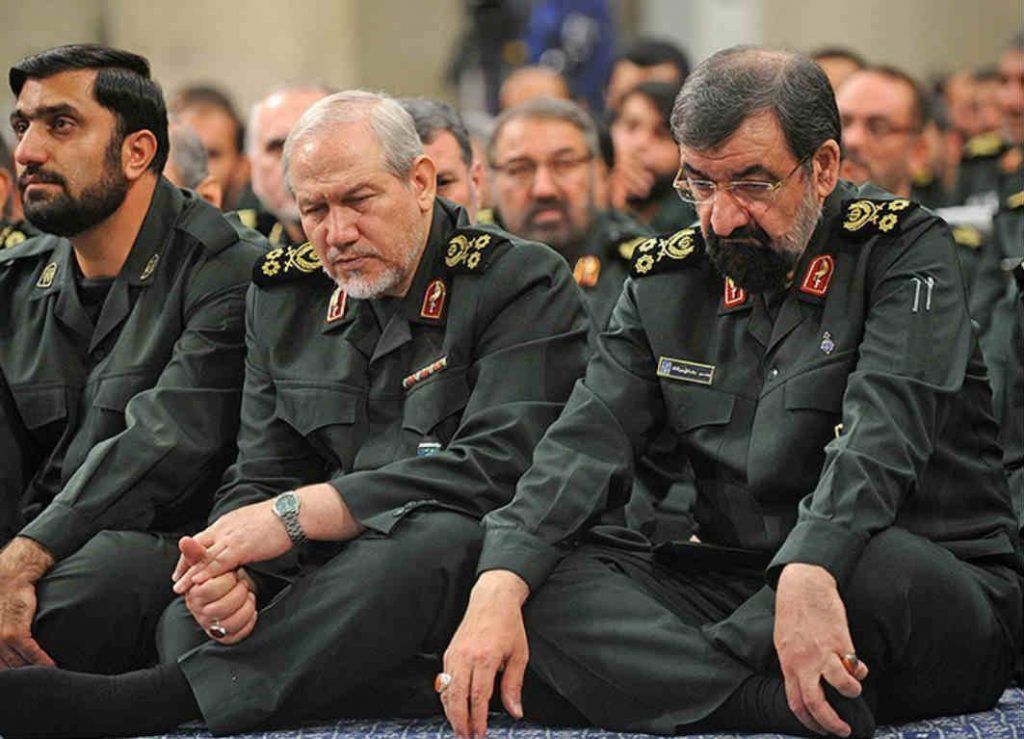

Actions by the two banks exposed the hostility between the IRCG and President Hassan Rouhani, whose government had adopted “recommendations” by the FATF (Financial Action Task Force, a coalition of 38 countries combating money-laundering and terror-financing).

The fight between these two major branches of the government has been waged in the media and in the streets. IRGC agents have attacked and set fire to a few branches of Bank Mellat and Sepah Bank. Conspicuously, the Majlis (Parliament), the Judiciary, the Supreme National Security Council, and even Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, have stayed out of the fray.

Following the implementation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action ( JCPOA, Nuclear Deal or BARJAM) in January 2016, President Rouhani warned of more plans of action. The move against IRGC – in line with FATF’s recommendations – could be interpreted as part of Rouhani’s comprehensive plan to ensure that Iran would receive the badly-needed economic relief following the nuclear deal.

During their annual meeting earlier this year in Seoul, South Korea, FAFT members praised Rouhani’s government for adopting the supervisory body’s recommendations and gave Iran one year to implement them.

In compliance with the government’s initiative, Iran Central Bank agreed to enforce FAFT’s “Forty plus Nine” recommendations. FAFT will review Iran’s banking measures and the efforts by the Rouhani government to battle money laundering after one year. The decision whether to give the green light to international banks to engage in currency trade with financial institutions and individuals in Iran, or alternatively to strengthen the sanctions, will depend on the FAFT’s findings.

The Iranian military has warned that government concessions to FAFT – aimed at removing Iran from the blacklisted countries and paving the way for Tehran to normalize relations with international financial institutions – could significantly diminish the regime’s influence in the region.

With the next presidential elections just around the corner, Hassan Rouhani, who has failed to deliver on his domestic economic promises, badly needs a win in his propaganda war against the military and the conservatives. His government considers the move against IRGC, and adopting the FAFT’s recommendations, as effective measures to ultimately win over the public.

Money laundering, a treasured sport

Money laundering and bureaucratic efforts to combat it has had a long history in Iran – a sobering fact that the government of President Rouhani has wrestled with over the past three years.

Smuggling and dealing in the black market became standard practice shortly after the formation of revolutionary committees (law enforcement forces) in 1979. One of the masterminds was Mohammad Montazeri (a.k.a “Hojatoleslam Ringo”), the son of one of the founders of the Islamic Revolution ,Hossein-Ali Montazeri.

The eight-year war with Iraq and the need to purchase arms had apparently legitimized IRGC’s dealings in the black market, and even its involvement in drug smuggling and human trafficking was ignored.

Powerful bodies not under government control that exert a great deal of influence on the country’s economy, such as the Committee for the Implementation of Imam Khomeini’s Orders, with a budget of 100 billion dollars controlled by Ayatollah Khamenei, and financial institutions closely affiliated with the IRGC, have turned money laundering into a sport.

In February 2008, Majlis passed an “anti-money laundering” bill with 12 articles and seven clauses. It was ratified by the Guardian Council (powerful supervisory body) and forwarded to the government two weeks later. Subsequently, the government set up an anti-money laundering council headed by the finance minister with the director of the Central Bank and a few other ministers as its members.

Money laundering methods

The involvement of major banks in laundering money for the Iranian regime, and the enormous sum of money that was being moved around, finally attracted the attention of the US Congress and the European Parliament.

In 2007, Lloyds TSB was found guilty by a Manhattan district court of laundering money for Iran. The bank agreed to forfeit $350 m to law enforcement authorities in the United States. Nine other banks were also found to have laundered money for Iran and fined a total of $10 b. These substantial sums demonstrate the extent of Iran’s involvement in money laundering operations.

The scheme involved deposits of large sums of money in various foreign banks. Converting the funds into the US dollar, the bank would then change the name of the account holder, divide the money into smaller sums, and redeposit the funds into other banks. Those banks would transfer the money into designated accounts under the control of the original depositor. The identity of the account holder remained hidden to ensure that the transactions went through New York without raising flags.

Iranian Banks would transfer large amounts of money to their foreign branches to facilitate transfers between accounts and banks. The money which was channelled through Lloyds TSB reportedly ended up in Afghanistan, Lebanon, the West Bank, and Gaza. Funds earmarked for Syria were reportedly delivered in cash on passenger planes traveling to Damascus; and, Venezuelan banks were used to funnel money through legitimate companies that had dealings with the Assad regime.

The practice continued until 2012 when the US and European sanctions placed severe restrictions on foreign banks engaging with Iran. This forced the regime to revert to its age-old modus operandi of conducting business transactions with suitcases stuffed with cash.

[responsivevoice_button voice=”US English Female” buttontext=”Listen to this “]