February 21, 2017

By Firooze Remezanzade

In a joint letter to the head of Iran’s judiciary, Dr Ketan Desai, president of the World Medical Association (WMA), has expressed grave concern over the mistreatment of political prisoners in Iran. He has urged the Iranian authorities to stop using the denial of medical treatment as a form of punishment.

Other signatories to the letter, namely the Standing Committee of European Doctors, the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims, and the International Federation for Health and Human Rights Organisations have condemned prison authorities in Iran for “depriving prisoners of medical treatment, refusing to transfer severely ill prison inmates to hospitals with better facilities, failing to provide hot water for bathing, housing inmates in cramped cells, and physically and sexually abusing prisoners, specifically during transfers to hospitals or courts.”

The letter continues, “We are extremely concerned by the situation that precludes access to adequate medical care, a key human right which under international law and standards must not be adversely affected by imprisonment.”

A report released by Amnesty International in July 2016 censured Iran’s judiciary and prison authorities for their mistreatment of political prisoners, and in some cases, denying medical care to inmates. The lack of adequate medical care is not peculiar to political prisoners; inmates convicted of other crimes are also deprived of basic health care. The head of Iran’s State Prison Organization warned in 2011 that HIV infection and AIDS had become a major problem among those incarcerated, particularly the drug addicts who share needles.

Even some senior government officials in Iran have expressed concerns over the dreadful conditions inside prisons. Iran’s Justice Minister, Mostafa Pourmohammadi, said in 2015 that out of every 100,000 Iranians 269 were in jail. Prisons in Iran are over-populated by double their capacity.

During a speech in July 2016, Iraj Harirchi, deputy health minister, cited overcrowded cells as the main reason for horrendous conditions in prisons.

In October 2016, a group of political prisoners in ward 12 of cell block 4 of Rajai Shahr prison, near Karaj, a town 20 km west of Tehran, sent a letter to Asma Jahangir, United Nations Special Rapporteur-Designate for Human Rights in Iran. They complained about the failure of prison authorities to provide proper medical care that in many cases had led to the slow and agonizing deaths of inmates.

In a conversation with Kayhan-London, M.H., a prisoner of conscience who has been incarcerated at Rajai Shahr prison for the past four years, said, “In most cases, a prisoner has to pay for the doctor’s visit and prescription. However, it is very difficult to get a permit to buy medicine. The law says that the coroner’s office has the jurisdiction over the release of a seriously ill prisoner if the inmate is not serving a life sentence. Nevertheless, Tehran’s Justice Department frequently overrides the coroner’s decisions and does not even grant a temporary release to inmates in need of urgent medical care.”

According to M.H., authorities at Rajai Shahr prison simply refuse to provide medical care to many prisoners of conscience and social activists who have been charged with “moharebeh” (being enemy of God). The list includes Afif Naiemi, Adel Naieme, Kourosh Ziari, Farhad Eqbali, Khaled Hardani, and Navid Khanjani, whose plight has received media attention.

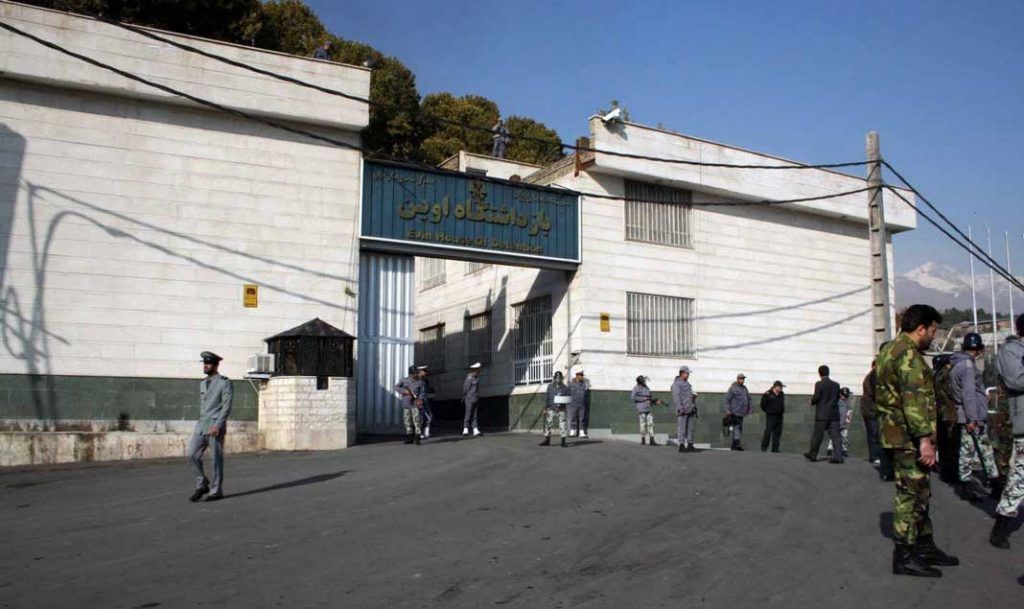

In a conversation with Kayhan-London, Mandeh Soltani, daughter of jailed Iranian human rights lawyer, Abdolfattah Soltani, said, “Evin prison’s infirmary is ill-equipped and can only provide rudimentary medical treatments. A specialist doctor visits the infirmary every few months, and on those occasions sick inmates have to wait in a long queue to be examined. Frequently, prisoners with serious ailments do not get the chance and have to wait another month or so before seeing the specialist.”

Mandeh’s father suffers from a digestive disorder, high blood pressure, and has lost a lot of weight. Prison authorities have refused to transfer him to a hospital with better medical facilities. Speaking about the inhumane treatment of political prisoners, Mandeh said, “The authorities ask families of prisoners to sign an affidavit committing to shoulder medical expenses, but in most cases families cannot afford the hospital bills and prisoners are not transferred to hospitals. On a number of occasions the authorities have refused to transfer a sick prisoner to the hospital of the family’s choosing. Those decisions are made by security agencies and not prison authorities.”

Mandeh cites a number of instances when young and healthy men and women have developed serious conditions while incarcerated. Illnesses have gone undetected, undiagnosed, or left untreated mainly due to poorly equipped infirmaries, absence of competent doctors, and overall negligence on the part of prison authorities.

There are also major concerns regarding the quality of food, unsanitary cells, unhygienic environment, poor lighting, and inadequate ventilation at most prisons in Iran. Highlighting the Evin prison’s dismal meal programme, Mandeh Soltani, said, “Prison authorities reportedly have a food budget of $0.90 per inmate. That is simply outrageous. Red meat is not part of the diet and only the lean and bony parts of chickens are used. Inmates routinely find pebbles, hair, and other foreign material in their food. Also, families of prisoners with special dietary requirements are unable to send food to prisons.” Mandeh added, “In addition to poor diet and unsanitary environment, prisoners are prevented from meeting with their families or lawyers. Inmates at Evin prison are not allowed to even call their families. Denying their basic human rights places a great deal of emotional and psychological pressure on the prisoners.”

Mandeh claims that the authorities deliberately place prisoners of conscience into the general prison population. They encourage convicted criminals to bully political prisoners, frequently resulting in fights.

Speaking to Kayhan-London, H.A., another prisoner of conscience in cell block 4, said, “Although subjecting inmates to loud jamming frequencies is against the law, the authorities at Rajai Shahr continue the practice which is detrimental to the well being of prisoners and guards alike. He also believes that lack of adequate ventilation has severe adverse affects on the health and well being of the 80 inmates housed in the cell.

H.A. added, “The enclosed cell and small windows covered with screens make it impossible for air to circulate. People with heart problems and breathing difficulties suffer the most. The prison is not equipped with an air circulation system. They don’t even remove the screens from the windows to allow fresh air to come in.” According to H.A. the quality of prison food is so bad that inmates cook their own meals which puts extra financial pressure on their families.

According to the latest report from Iran, Urumiyeh, Tabriz, Sanandaj, and Mahabad prisons have the worst standard of food, health, hygiene, and medical care in the country.