SOURCE: THE CONVERSATION

Associate Lecturer, Department of Politics, University of York]

Just over six months ahead of the US election, the world is starting to consider what a return to a Trump presidency might mean. While Americans might be weighing up the difference between the two candidates domestic policies, the rest of the globe is more interested in what foreign policy decisions he might make.

Donald Trump has already hinted at some areas he is particularly likely to address: China, Nato, Ukraine and Gaza among them. Recent statements during the campaign and leaked memos – as well as his last stint as president signal moves that may be ahead.

“A handful of successes — and many more failures” is how Harvard professor of international affairs Stephen Walt describes Trump’s global decisions in his first term.

Joel Rubin, deputy assistant secretary of state for legislative affairs in the Obama administration, characterised Trump’s “America First” catchphrase as “America first, but really America alone”, emphasising Trump’s isolationist credentials. But could his assertive attitudes to other nations have some positive fallout?

Trump had a mixed relationship with Nato in his first term. After declaring the organisation “obsolete” in January 2017, he later backtracked on this position. However, much of the damage with America’s Nato allies had already been done, and relations remained frosty.

Trump has been hinting that if reelected he would cut US funding to Nato or indeed not stand by article 5 of its founding treaty, which says that if one Nato member was attacked militarily, others would come to their aid. This has already caused concern across Europe.

Some European allies have taken heed of Trump’s early warnings, and are now starting to increase their defence spending and, in some cases, increase military recruitment and reservist numbers to help deter Russia.

Some might argue that Trump’s intention when he made these comments was to increase the military capacity and spending of America’s European allies – and might suggest this is already a Trump success.

Trump is not the first US president to call on Nato allies to spend more on defence, in fact most US presidents have had the same message for Nato. Where Trump differed was in the severity of his comments and the threatening manner of his delivery.

A former Trump administration secretary of defense, James Mattis, reported that in his initial meetings with Trump he had fought to persuade Trump that “if we didn’t have Nato Trump would want to create it”.

Yet, in a second administration, Trump is likely to appoint far fewer establishment figures who want to stand up for international alliances. There are reports that a special unit has been set up to select new appointees that are completely onside with Trump’s perspective, ahead of November.

In his previous term Trump was heavily focused on US-China competition and how the relationship between the two countries needed to change. As a candidate and as president, Trump made the battle between the US and China a big part of his foreign policy rhetoric.

In January 2020 Trump announced almost $360 billion (£268 billion) of tariffs on products from China, seeking to encourage US shoppers to buy American goods instead. Despite this, the consensus on these measures is that they actually caused damage to both the US and Chinese economies.

A return of Trump to the Oval Office is likely to signal a return to this tough approach towards China. In his interview with Time magazine, he suggested tariffs of more than 60% on Chinese goods were part of his plan. While his previous tariffs may not have been deemed a success, there is every reason to suppose that Trump will once again pursue a similar tough-on-China policy if elected.

Another theme from Trump’s first time in office that is likely to crop up again is his relationships with particular leaders and autocrats, whose rhetorical style was somewhat similar to his. From Vladimir Putin to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Kim Jong-Un to Jair Bolsonaro, Trump’s interactions with other world leaders were noted for how friendly and complimentary he was to these “strongman” characters.

Trump’s relationships with these leaders tend to leave him believing this gives him more influence with them. This inflated idea of his power may have provoked his statement that he can “solve the Ukraine war in a day”. But examination of his previous record shows that his “friends” do not always fall in line.

When, in 2019, Trump wrote to Erdoğan urging him not to launch military action against Syrian Kurdish forces, the Turkish president clearly ignored his advice.

Trump has indicated that he would not fund the Ukrainian government in its fight against the Russia invasion if he became president, calling for Europe to shoulder the financial burden. This statement may leave Putin feeling that he dosn’t need to hold back military advances in Ukraine, or worry about a US response.

Trump has described himself as the “most pro-Israel” president in history, and his Peace to Prosperity plan has been described as a monumental shift from previous attempts.

The plan proposed legitimising Israeli settlements in the West Bank, establishing East Jerusalem as the Palestinian territory’s capital and, according to the PLO, giving the Palestinians control of just “15% of historic Palestine”.

Trump also controversially moved the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, which provoked criticism from Muslim leaders. Jerusalem is claimed by both Palestinians and Israel as their capital. But recently he has been hinting that he was not happy with the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and was critical of his leadership.

Given this legacy from his first term, it is doubtful that a second Trump administration would be able to bring parties together for negotiations in the current conflict in Gaza.

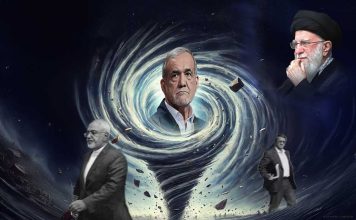

Iran and the threat it posed was once a key focus for Trump. His response to the recent Iranian drone attack on Israel demonstrates that this is likely to be the same in 2025 if he is elected. Trump reposted a tweet aimed at the Iranian leadership from 2018, where he warned the Iranian president to be cautious about threatening the US. Trump is likely to continue this aggressive rhetoric towards Iran.

Based on campaign remarks and his previous policies, another Trump presidency threatens to deepen US isolationism and backslide on US commitments to international bodies. Given this Trump 2.0 foreign policy, it is hard to see any positives in foreign policy for the rest of the west from a Trump victory this November.