SOURCE: THE CONVERSATION

The devastating attack on Israel by Hamas on 7 October has transformed the Middle East, thrusting the Israeli-Palestinian question – considered a diplomatic side-issue for at least a decade – to the centre stage of the region’s geopolitics.

Iran’s proxies have come out of these events strengthened, with players manoeuvring in a complex power game that could at any moment tip into a regional war. It is still possible to avoid such a scenario through a negotiated cease-fire.

We are entering uncharted territory, with Israel’s political and military objectives as of yet not clearly defined. This makes this war of revenge different from all previous Israeli operations against Hamas, whether in terms of duration, objectives or the number of victims on both sides.

The rhetoric of Israeli officials, some of whom have denied the existence of innocent civilians in Gaza, has oscillated between maximalism and minimalism, including calls for a total occupation of Gaza notwithstanding the US president’s warnings, the creation of a buffer zone, and the “simple” destruction of Hamas infrastructure.

On 7 October, as Hamas launched its unprecedented operation, its military commander, Mohammed Deif, called on all Arabs and Muslims and, especially, Iran and the states and organisations it dominates, to launch an all-out war against Israel. He mentioned, in order, the Lebanese Hezbollah, Iran, Yemen, the Iraqi Shiite militias and Syria. He proclaimed the date as “the day when your resistance against Israel converges with ours”, in what is known as a “unity of fronts”, a strategy of deterrence initiated by Hezbollah.

The latter consists in coordinating the responses of all of Iran’s proxy militias in the region and carrying out collective defences in the event that one of them is attacked. The many fronts dominated by Iran’s proxy militias could then dissuade Tehran’s adversaries from taking action or, on the contrary, accelerate the region’s descent into total chaos.

After 7 October, the security situation rapidly deteriorated on Israel’s Lebanese border, with increasingly intense skirmishes between Tsahal and Hezbollah.

Two noteworthy elements have also emerged on the Lebanese front. For the first time since the end of the civil war, we have witnessed the “temporary” resurgence of the Al-Fajr forces, the military wing of Jamaa Islamiya. This Lebanese Sunni Islamist militia, which was disbanded in 1990, announced that it was taking part in hostilities beyond Israel’s Lebanese borders “in defence of Lebanese sovereignty, the Al Aqsa mosque and in solidarity with Gaza and Palestine”. On 29 October, it launched missiles from Lebanon towards Kiryat Shmona, in northern Israel. This militia fights almost independently of Hezbollah (although there is military coordination between the two organisations).

In addition, Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Lebanon have issued communiqués taking full responsibility for several attacks against Israel launched from the Lebanese territories. This recalls the years when southern Lebanon was dominated by the military activities of the Palestinian PLO (from 1969), to the point of being nicknamed “Fatah Land”.

While their participation in the hostilities is still limited, it matters in symbolic terms. It is clear that Hezbollah is coordinating the activities of all the militias operating on the Lebanese border to send out a clear message: the area is open to all Islamist and non-Islamist factions, who are invited to join, even symbolically, in the fight against Israel in order to express their solidarity with Gaza. In other words, Hezbollah declares that this struggle is not sectarian, but unites Muslims and concerns all Arabs and Muslims.

This message of Muslim unity against Israel comes after years of sectarianism in the Middle East. Hezbollah has carried out only limited attacks against Israel since the end of the Israel-Lebanon war in 2006, and even intervened in Syria to support Hamas’ then-enemy, Bashar Al-Assad.

This stance made Hezbollah very unpopular with the Sunni populations of the region. By joining the fight against Israel, Hezbollah is reaffirming itself in the eyes of all Arabs in the region not as a sectarian player, but rather as an Islamic revolutionary group that aims to put an end to Israeli arrogance.

This reframing corresponds to the story it tells about itself. Hezbollah sees itself as a model for Hamas and other Islamic forces fighting Israel. Despite their differences over the war in Syria, they restored relations in August 2007 and senior Hamas commanders, such as Ismael Haniyeh (the head of Hamas’s political bureau) and Yahia Sinwar (head of Hamas’s political bureau), publicly thanked Iran for its invaluable help with funding, logistics and arms supplies.

The Hamas attack came at a time in the Middle East when the United States had been attempting to extend the Abraham Peace Accords to Saudi Arabia.

Aimed at laying the foundations for a new security architecture in the Middle East that would benefit the US and its allies, the agreement had led to a rapprochement between Israel and several Arab states under Washington’s watch. However, it is now under threat, while any prospect of normalisation between Israel and Riyadh also appears highly unlikely.

For Washington, this predicted outcome is all the more damaging that it comes months after the Chinese achieved a major diplomatic success by negotiating a détente between Saudi Arabia and Iran, which for years had backed the Houthi militias fighting Saudi Arabia in Yemen. As part of this rapprochement between Riyadh and Tehran, talks were held between the Houthis and the Saudis to support the peace process in Yemen.

The Houthis are another part of the Iranian axis in the region. Their rise as a Yemeni political and military player has emboldened them. They have declared that they are ready to join Hamas in an all-out war against Israel to defend Gaza and the Al-Aqsa Mosque. As a show of force, on 19 October they launched three cruise missiles and drones which were intercepted by a US destroyer in the Red Sea. According to the United States, these missiles were “potentially aimed at Israel”. The attack is symbolic in itself, but it sends a strong political message that reaffirms the strategic primacy of the Houthis’ links with the Iranian-backed “axis of resistance” and signals the militia’s willingness to engage militarily in regional or international wars or tensions.

This was clearly defined in their leader’s speech. The Houthis have a formidable arsenal of long-range missiles that would be capable of striking Israel. All of them were either seized from the Yemeni state in 2014 or transported by Iran.

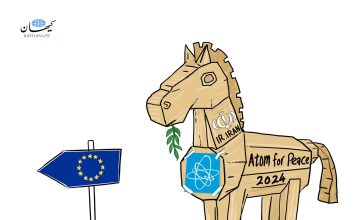

The missile attacks by the Houthis coincided with other attacks by Iranian-backed Shia militias, targeting US bases and garrisons housing US soldiers in Iraq and Syria. Iran has strategically outsourced the risk of direct confrontation with the United States and Israel via its “axis of resistance”: when such attacks take place, it is not directly responsible. This positioning increases its influence in direct and indirect negotiations, as well as its regional influence.

Players, in conclusion, seem to be walking along the crater of a volcano. They are all waiting to learn more about the political and military objectives of Israel’s war in Gaza and to be able to assess Hamas’s capacity to resist the attack on it.

If the Israeli army records significant losses, the strategic position of the Iranian-backed axis will improve, at no cost to Tehran (but at a very terrible cost to the people of Gaza).

But what would happen if Israel threatened the very existence of Hamas after a ground invasion? Would the intense skirmishes on Israel’s Lebanese borders turn into a full-blown war? Would Iran join the hostilities? What if Israel felt strengthened by the West’s unconditional support for its right to defend itself and took this solidarity as a license to strike Iran, whose nuclear ambitions frighten the Hebrew state’s leaders? In such a scenario, and faced with Tehran’s response, will the United States use its destroyers in the Eastern Mediterranean to attack Iran and defend Israel?

At this stage, it is impossible to give a clear-cut answer to all these questions. All we can say is that the region seems to be heading for a new phase in which the sectarianisation of the foreign policies of the regional players will be relegated to second place, détente between Iran and Saudi Arabia will be consolidated, the Palestinian question will come to the fore for a long time to come, and the Iranian proxy militias will become increasingly assertive.