By Francois Murphy

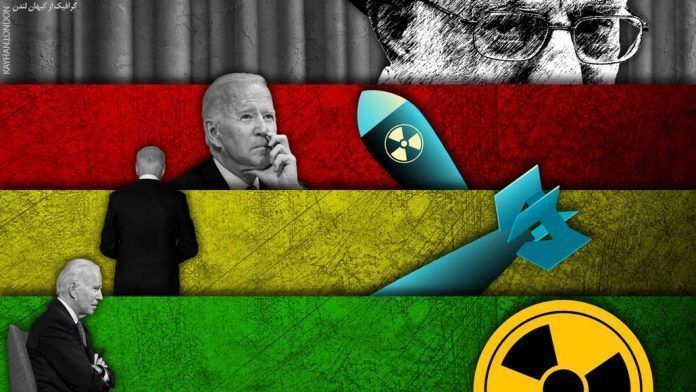

VIENNA, Nov 28 (Reuters) – Talks on reviving the 2015 Iran nuclear deal are to resume in Vienna on Monday, with Iran‘s atomic advances raising doubt as to whether a breakthrough can be made to bring Tehran and the United States back into full compliance with the accord.

Since the United States under then-President Donald Trump withdrew from the deal in 2018, Iran has breached many of its deal’s restrictions designed to lengthen the time it would need to generate enough fissile material for a nuclear bomb to at least a year from 2-3 months – the so-called “breakout time”.

Iran says it only wants to enrich uranium for civil uses. But many suspect it is at least seeking to gain leverage in the indirect talks with the United States by getting closer to being able to produce a nuclear weapon.

How close is Iran to being able to do so, and what remains of the deal’s restrictions?

BREAKOUT TIME

Experts generally put breakout time at around three to six weeks but say weaponisation would take longer – often roughly two years. Israel’s finance minister recently said Iran could have nuclear weapons within five years.

ENRICHMENT

The deal restricts the purity to which Iran can enrich uranium to 3.67%, far below the roughly 90% that is weapons-grade or the 20% Iran reached before the deal. Iran is now enriching to various levels, the highest being around 60%.

The deal also says Iran can only produce or accumulate, enriched uranium with just over 5,000 of its least efficient, first-generation centrifuges at one facility: the underground Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP) at Natanz.

The deal lets Iran enrich for research, without accumulating enriched uranium, with small numbers of advanced centrifuges, which are often at least twice as efficient as the IR-1.

Iran is now refining uranium with hundreds of advanced centrifuges both at the FEP and the above-ground Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant (PFEP) at Natanz.

It is also enriching with more than 1,000 IR-1s at Fordow, a plant buried inside a mountain, and plans to do the same with more than 100 advanced centrifuges already installed there.

URANIUM STOCKPILE

The International Atomic Energy Agency, policing Iranian nuclear activities, estimated this month that Tehran’s stock of enriched uranium is just under 2.5 tonnes, more than 12 times the 202.8-kg (446-pound) limit imposed by the deal, but less than the more than five tonnes it had before the deal.

That said, it is now enriching to a higher level and has around 17.7 kg of uranium enriched to up to 60%. It takes around 25 kg of weapons-grade uranium to make one nuclear bomb.

INSPECTIONS AND MONITORING

The deal made Iran implement the IAEA’s so-called Additional Protocol, which allows for snap inspections of undeclared sites. It also expanded IAEA monitoring by cameras and other devices beyond the core activities and inspections covered by Iran‘s long-standing Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement with the IAEA.

Iran has stopped implementing the Additional Protocol and is allowing the extra monitoring to continue only in a black-box-type arrangement, whereby the data from cameras and other devices is collected and stored but the IAEA does not have access to it, at least for the time being.

The one exception to the continued monitoring is a centrifuge-parts workshop at the TESA Karaj complex, which was hit by apparent sabotage in June that destroyed one of four IAEA cameras there, after which Iran removed all of them. Iran has not let the IAEA re-install the cameras since.

POTENTIAL WEAPONISATION

Iran has produced uranium metal, both enriched to 20% and not enriched. This alarms Western powers because making uranium metal is a pivotal step towards producing bombs and no country has done it without eventually developing nuclear weapons.

Iran says it is working on reactor fuel.

(Reporting by Francois Murphy Editing by Mark Heinrich)