AKTAU, Kazakhstan, Aug 12 (Reuters) – Iran and four ex-Soviet nations, including Russia, agreed in principle on Sunday how to divide up the potentially huge oil and gas resources of the Caspian Sea, paving way for more energy exploration and pipeline projects.

However, the delimitation of the seabed – which has caused most disputes – will require additional agreements between littoral nations, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said.

One of those is a pipeline across the Caspian which could ship natural gas from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan and then further to Europe, allowing it to compete with Russia in the Western markets.

Some littoral states have also disputed the ownership of several oil and gas fields, which delayed their development.

POST-SOVIET ISSUE

The dispute began with the fall of the Soviet Union which had had a clearly defined Caspian border with Iran. In negotiations with post-Soviet nations, Tehran has insisted on either splitting the sea into five equal parts or jointly developing all of its resources.

None of its neighbours have agreed to those proposals and three of them – Russia, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan – effectively split the northern Caspian between each other using median lines.

Azerbaijan, however, has yet to agree on how to divide several oil and gas fields with Iran and Turkmenistan, including the Kapaz/Serdar field with reserves of some 620 million barrels of oil.

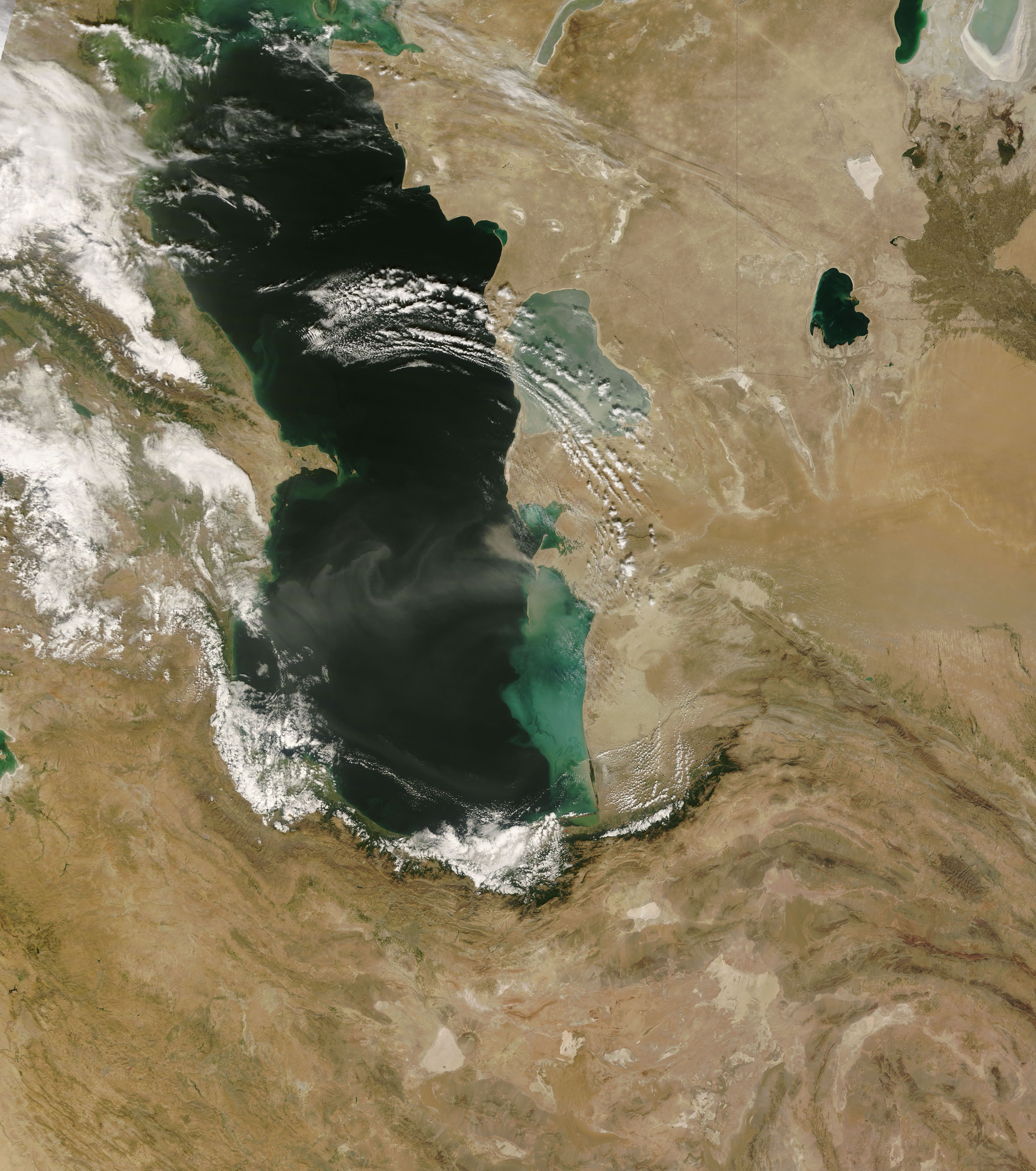

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Caspean-Sea.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”FILE PHOTO: Pump jacks pump oil at an oil field on the shores of the Caspian Sea in Baku, Azerbaijan, October 5, 2017. Picture taken October 5, 2017. REUTERS/Grigory Dukor” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

The three countries have tried to develop the disputed fields while at times using warships to scare off contractors hired by other sides. As a result, none of the disputed projects has made much progress.

Speaking after the signing on Sunday, all five leaders praised it as historic event, but provided little detail about provisions on splitting the seabed.

However, making it clear that the document is no final solution, Rouhani said border delimitation would require further work and separate agreements, although the convention would serve as a basis for that.

TRANS-CASPIAN PIPELINE

Moscow has no outstanding territorial disputes but has objected, citing environmental concerns, to the construction of a natural gas pipeline between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan which would allow Turkmen gas to bypass Russia on its way to Europe.

It remained unclear whether the convention adopted on Sunday would definitely clear a way for the pipeline. Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev said the document allowed pipelines to be laid as long as certain environmental standards were met.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Caspean-sea-2.jpg” panorama=”off” align=”center” lightbox=”on” caption=”An oil rig (rear) and infrastructure of D Island, the main processing hub, are pictured at the Kashagan offshore oil field in the Caspian sea in western Kazakhstan August 21, 2013. REUTERS/Stringer/File Photo” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”inplaceslow” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Ashley Sherman, principal Caspian analyst at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, said that although the signing itself was “an unprecedented milestone” for the region, the immediate implications for the energy sector would be limited.

“We consider a Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline (TCGP) unlikely, even in the longer term”, he said in an email. “Clarity on the legal status will shine more light on the commercial and strategic obstacles to a TCGP, from infrastructure constraints to supply competition, not least from Azerbaijan itself.”

In the upstream sector, the increasing intent for joint projects in the south Caspian is very promising, Sherman said.

“Stranded fields and frozen exploration projects may well come back on the agenda,” he said.

However, with offshore Caspian oil and gas production already almost at 2 million barrels of oil equivalent per day, the impact from new fields – if and when disputes about their ownership are settled – might be limited.

“The scale of the projects in disputed waters is not comparable to the existing super-giant fields, from Azeri Chirag Guneshli and Shah Deniz in Azerbaijan to Kashagan in Kazakhstan,” Sherman said.

(Reporting by Olzhas Auyezov; Editing by Richard Balmforth)