By Roshanak Astaraki

The current economic crisis has had the most severe impact on Iran’s poor and working classes. Factory closures and company bankruptcies have resulted in massive job losses. Persistent drought and a severe water shortage have destroyed crops, leaving many farmers around the country with no means of making a living. Industrial and manufacturing plants have not paid their workers for months.

Single-income working-class households are finding it extremely difficult to make ends meet. Most of them have been living hand to mouth. The rising cost of living has pushed many workers and day laborers to the brink of poverty. There are reportedly 13 million workers in Iran.

In the spring of 2018, workers’ unions demanded a general wage adjustment in line with the cost of living and the rate of inflation. The Supreme Labor Council, which is a department of Iran’s Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, had previously set the national minimum wage for workers at $239 a month. Yet between April and December, the rial continued to lose value against major foreign currencies while the price of goods skyrocketed. Labor activists pointed out that the purchasing power of workers had diminished significantly and called on the government to address the issue promptly.

Faramarz Tofighi, a labor activist, said: “Until 2012, the national minimum wage was 57 percent lower than the cost of living. There was a huge gap between the amount of money that minimum wage workers made and what they needed to live. However, the gap had narrowed by 12 percent in recent years until 2018 when it rose to 87 percent.”

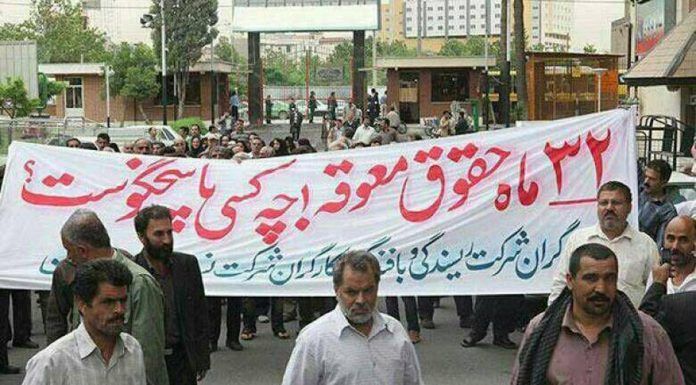

The government has not increased the national minimum wage in the past year. Workers and day laborers are the main victims of the Iranian government’s failed economic policies, and have paid the most substantial price for the U.S. sanctions. Many manufacturers and industrial production plants have been experiencing a severe cash-flow problem which has forced them to reduce their workforce. Since April, many factories have fired thousands of workers who had not received their wages for months. Meanwhile, those with jobs face an uncertain future. Companies owe these workers months of back pay. However, their meager wages cannot keep up with the increasing cost of living.

The government is planning to review the national minimum wage in the coming year. Meanwhile, workers’ unions demand that new figures must factor in inflation rate and close the gap with the cost of living. One of the more contentious issues is the worker’s housing allowance. The Supreme Labor Council has proposed $24 as the new housing allowance at the start of the Iranian new year on March 21, which falls way short of what a family needs for renting a house. A household could not rent a room let alone an apartment for that amount in Tehran or other major cities.

The government also discriminates against workers. For instance, a recent financial aid plan aimed at providing cash subsidies to poor and disadvantaged households excludes many workers and their families. According to Ali Khodaei, a member of the Supreme Labor Council, only workers who have Social Security Insurance can receive financial aid. The guideline excludes 8 million workers who do not have insurance.

According to the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, workers’ associations and councils have grown by 56 percent in recent years. However, this does not mean that workers’ unions and guilds can operate freely in Iran. The government’s continued disregard for the welfare of workers has galvanized labor activists and groups to demand job security, higher wages, and safe work environment.

Although the Islamic Republic Constitution allows peaceful civil disobedience, security forces have tried to crush all recent protests by factory workers around the country. Workers at the Khuzestan Steel Company and Haft Tappeh Sugarcane Factory in Ahvaz, the capital of the southern province of Khuzestan, went on strike in November for ten days demanding their back pay. Authorities brutalized and jailed many of them.

Esmail Bakhshi, a worker at the Haft Tappeh Sugarcane Factory, was arrested by security police and spent 20 days in jail where he suffered physical and psychological abuse. After his release, he spoke publicly about his ordeal in prison which prompted authorities to extract a forced televised confession from him before putting him back in jail.

The Iranian government must understand that brutalizing, arresting, torturing and imprisoning people who demand their back pay does not solve the problem of 13 million workers who are struggling to provide for their families under difficult economic conditions. By arresting labor activists, the state may temporarily disperse protesters, but it cannot silence a large segment of Iranian society who demand better wages and safer work conditions.

Translated from Persian by Fardine Hamidi