By Firouzeh Ramezanzad

On February 11, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei delivered a message to the nation to mark the 39th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution.

Describing people’s participation in the rallies as “dazzling,” Mr. Khamenei said: “Celebrate this occasion by decorating your homes. Use your creativity and make ornaments from papers and other material. Don’t use light bulbs and save on electricity. That’s sensible. Instead, put up flags outside your houses. Cover the streets with the Islamic Republic flags. Show the world that Iranians cherish this day.”

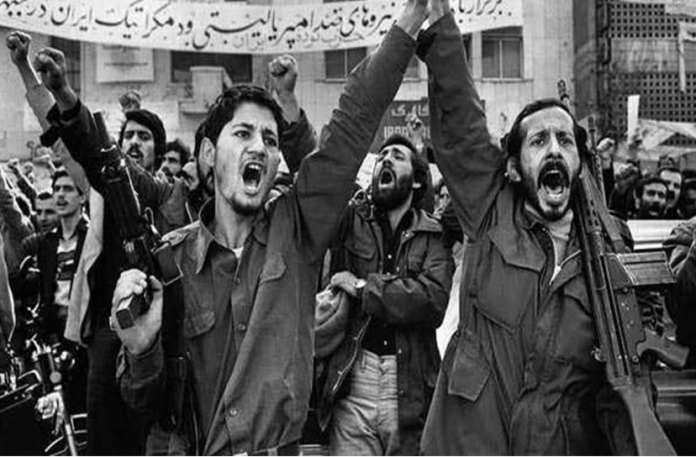

The ten-day celebration (February 1 through 11) I s known as the Fajr Decade, or decade of dawn, marking the return of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Revolution, to Iran in 1979. Many people in Iran, however, sarcastically refer to the occasion as the Zajr Decade, or decade of suffering.

The regime spared no expense this year in its nationwide celebrations. Towns and cities around the country were plastered with banners, murals, lights, and flags. Revolutionary music videos and films were broadcast on statell TV and radio. Newspapers and internet sites were flooded with articles celebrating the achievements of the regime in the past four decades.

What has the Islamic Republic actually accomplished in the last 40 years, particularly for the post-revolution generation? We put this question to a number of Iranians who were born in the 1970s and 80s.

An employee of the automaker SAIPA, headquartered in Tehran, told Kayhan London that despair, depression, and unemployment were the true achievements of the regime. At 40 he has no hope of ever forming a family of his own. Despite having a degree in mechanical engineering, he cannot envision a prosperous future for himself in the current economic climate.

He said: “How can we consider poverty, corruption, discrimination, unemployment and the high cost of living as achievements? Judge for yourself. I’m not saying that the Pahlavi Dynasty wasn’t corrupt, but I also think that the rule of the reformists has come to an end. This type of revolution is more harmful than helpful. I believe in revamping the whole system.”

“Has the revolution truly achieved anything?” a 39-year-old high school teacher asked. Highlighting economic mismanagement, corruption, and discrimination, this teacher told us: “People who benefit from the current system use their political and economic influence for financial gain. They take advantage of double-digit inflation.”

The teacher added: “People have developed a disdain for any kind of ideological and theocratic rule. The Islamic Republic cannot take credit for any of the technological developments. That is a global phenomenon. And to suggest that the regime has made any positive contribution to world culture would be disgraceful and beyond dishonest. We have advanced in the area of higher education. More people than ever obtain university degrees. Yet this is due to financial rather than educational reasons.”

A 19-year youth from the so-called “burned generation” — referring to Iranians born between 1972 and 1990 — said: “You are a journalist. You know better than I that the revolution has creaknows uselessly burned generation. The rich get richer and the poor get poorer. This revolution hasn’t achieved anything. But it has awakened the new generation.”

A nurse at Tehran’s Khatam Al-Anbia Hospital told Kayhan London: “As a social worker I witnessed firsthand the achievements of this revolution when I traveled around the country testing drug addicts, homeless people, and prostitutes for HIV and hepatitis. I saw underage girls selling drugs and young women selling their bodies. It drove me mad. Doctors, nurses, social workers and health professionals see people’s suffering up close. It’s painful.”

We spoke to a woman who had grown up in a religious family. She wore a full hijab, including the chador, all through high school. She told us: “Achievements?! What achievements? No one I know believes in the revolution and the Decade of Fajr. My husband doesn’t know about this, but I went to a birthday party at an exclusive restaurant the other day. It was held in a private room. Many people were there with their boyfriends and girlfriends.” She added: “I don’t believe in wearing the chador or the hijab. I only wear it because of my husband and family. Most of my friends think like me.”

We spoke to a 38-year-old woman who had stopped wearing the chador a few years ago. She said: “I don’t believe in wearing a chador. We were brainwashed in the 1980s. I used to smash cassette tapes of Western music which belonged to my older sister. What a horrible thing to do. I apologized to my sister years later. For years I thought like the religious police. Many of my friends had boyfriends but I didn’t look for one. I don’t like myself.”

These are the testimonies of a generation that has grown up in the post-revolution Iran. They’ve lived through an eight-year war – the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88), mass executions of political dissidents in the 1980s, the compulsory hijab, economic meltdown and unemployment. The second and third post-revolution generations hold a dim view of the regime. Many intellectuals, human rights advocates and political activists from these generations have lost their lives fighting for democracy and freedom. Many have spent years in jail or forced into exile.