By Ellahe Bograt

January 21, 2018 The genesis of the women’s movement in Iran can be traced back to the events that led to the Constitutional Revolution of Iran [1905-1911]. As a result of those events, women gained greater rights in Iran compared to other Middle Eastern countries. While the Islamic Republic has managed to restrict women’s rights in the past four decades, it has failed to eradicate them entirely. This is due to the men and women who have fought relentlessly for the human rights of all citizens. Women are neither the “second sex” nor the “second half.” They are simply the other sex, entitled to the same rights as men.

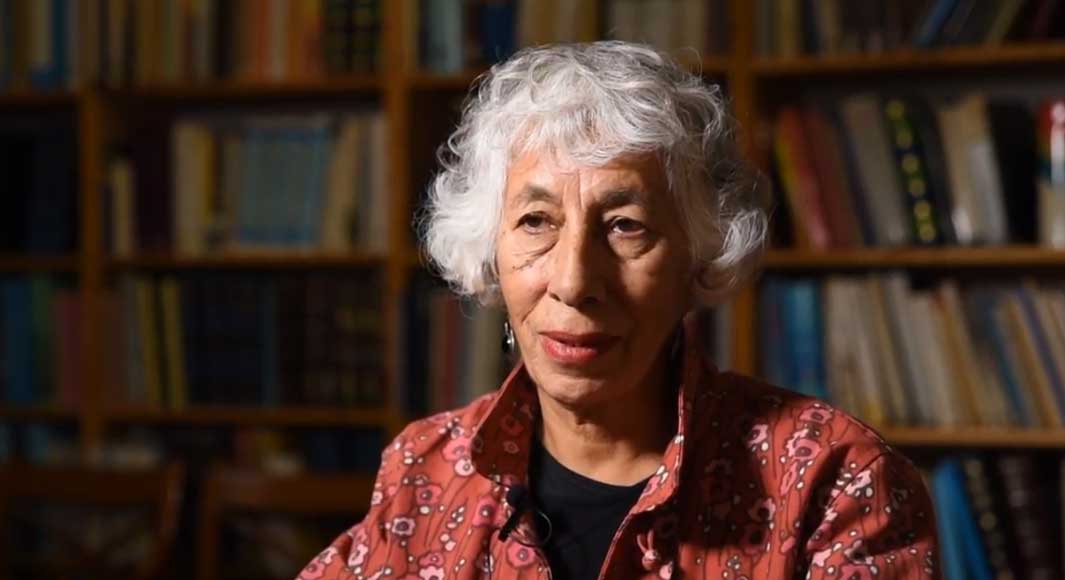

Kayhan London recently spoke about the movement with Mrs. Shahin Navai, researcher, women’s rights activist and former faculty member at Tehran University.

What did you teach at Tehran University and what was the atmosphere like for female university students at the time?

I was a faculty member of Tehran University’s School of Medicine. I specialized in medical entomology [public health entomology, focusing on insects that impact human health.] I taught at the School of Medicine and the Department of Pharmacology. But I mainly worked in the School of Health.

Female students, professors, and university employees studied, taught and worked in a much more open academic climate prior to the 1979 Islamic Revolution. At the time, It was quite acceptable for a woman such as myself to travel to different parts of the country for work, study or research. I was part of a four-member research team. My other three colleagues were all men. Women had worked very hard to create those opportunities for themselves.

But the situation drastically changed after the 1979 Revolution. Many restrictions were imposed on women. I’d like to speak about my own experience. The School of Health was an international institution. It offered postgraduate studies and masters degrees. It only admitted a limited number of Ph.D. candidates every year. Most students who enrolled in the program had previous work experience and were extremely enthusiastic about the specialized field of study that the school offered.

What I found quite upsetting was how my female students were treated. At the time, my best student was a young girl who was in her last year of study in medical entomology. She’d been at the top of her class the previous year. One day, we noticed that she had not attended any classes. We discovered that the [authorities] had expelled her from the university because she was of Bahá’í Faith. She was my best student.

At the other end of the spectrum was Mrs. Masoumeh Ebtekar [current Vice President of Iran for Women and Family Affairs.] She was also one of my students. She hardly attended classes. As far as I can remember, she only attended my class once. Also, she went on only one scientific field trip to collect sample specimens. It is unclear how Mrs. Ebtekar obtained her masters and Ph.D degrees, considering she wasn’t a good student.

The prevailing atmosphere was not helpful to hardworking students and teachers. We worked under greater constraints. Many university professors who were on contracts were dismissed after the Revolution. I had been made permanent, and, therefore, was able to keep my job. I was also able to resist complying with the mandatory hijab law until 1982 when many female professors left the university. I left Iran in 1983. I faced a number of problems which prompted me to leave Tehran and then Iran altogether.

You left Iran and faced a new set of problems as a woman and a refugee living in exile. How did you deal with the stigmas attached to being a Middle Eastern and Muslim asylum seeker in Germany?

I’ve been a women’s rights advocate all my life. I was one of the founders of the Iranian women national solidarity movement, one of the largest women’s rights groups in the country. I established contacts with women’s rights groups soon after arriving in Germany. I formed relationships with Iranian and German groups as well as journalists. I was able to exchange ideas with German citizens who were concerned about democracy and women’s rights within their own society. This opened a number of new doors and opportunities for me.

I was in my late 30s when I came to Germany. I encountered a number of problems and difficulties. My asylum application was initially rejected after my first interview because I had escaped to Pakistan before arriving in Germany. The immigration officer who interviewed me recognized my status as a political refugee, but the German government didn’t consider Pakistan as an unsafe country at the time. It took six years before I was finally granted an asylum.

Subsequently, I helped many refugees and women. I worked extensively with German women and journalists regarding rights issues. I didn’t experience the same problems that younger refugees, particularly men, normally face when they come to Germany. In other words, I didn’t experience racism until I applied for a job. One can argue that institutionalized racism has always existed in Germany. That doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist in other European countries.

I’ve been working closely with Iranian organizations which help political asylum seekers and refugees around the world. I’ve discovered that racism exists in many countries, but it is much more prevalent in Germany.

As you know, the women’s rights movement in Iran reached its peak around 15 years ago. But it suddenly lost momentum. It’s been dormant ever since. The rights advocates who were visible and active at the time nowadays briefly emerge during the elections in support of a particular candidate and disappear quickly afterward. Their roles have significantly diminished. They don’t have the same presence and influence as before. Do you agree with this assessment? And if so, why do you think this has happened?

In my view, the women’s movement in Iran has always been active and strong. But as you just mentioned, it has had its ups and downs. Iranian women have consistently and strongly opposed the mandatory hijab. Women groups have always maintained an uncompromising stance on this issue. The battle against mandatory Hijab started 20 days after a speech by Mr. [Ayatollah Ruhollah] Khomeini [the founder of the Islamic Republic] which prompted a massive and spontaneous protest in Iran. Women continue to protest the hijab law in various ways, including through White Wednesdays [a social media campaign which calls on women to wear a white headscarf or white clothing as the symbol of protest.]

If I’m not mistaken, the authorities launched over 12 nationwide security operations aimed at enforcing the hijab law. This is a clear evidence that Iranian society is a dynamic and not a static one. The rights movement reached its peak when the activists managed to collect over a million signatures in support of a petition which called on the state to recognize the inalienable civil and legal rights of women.

There are a number of reasons why the movement lost its momentum. There were some political disagreements and power struggle among the rights activists. There were also some elements who tried to exert influence from behind the scenes. There was a lot of pressure on rights advocates. The regime also intensified its crackdown on the movement which caused many activists to abandon their efforts. Authorities always try to crush a popular movement.

Women were extremely active during the 2009 presidential elections. Unfortunately, women’s groups failed to formulate their objectives very coherently during this period. They didn’t effectively articulate their demands, even though they received great exposure and widespread publicity. They even braved riot police and bullets. They retreated because the regime brutally crushed the movement. The authorities also prohibited any gatherings.

The Islamic Republic has tried to systematically wipe out any progress made by Iranian women. The regime has for instance locked and boarded up the Sediqeh Dowlatabadi Library [1882-1961, a feminist activist and journalist and one of the pioneering figures in the Iranian women’s movement.] No one is allowed to visit the place. It is unclear what they’ve done to all the books. The library was a place were literary enthusiasts would meet to read and review books. The Islamic Republic doesn’t even tolerate the existence of a library, let alone a feminist organization that promotes civil and legal rights of citizens.

Women have increasingly been ignoring the strict hijab dress code especially in recent years. Do you think that the Islamic Republic may lift the mandatory hijab at some point?

Hijab is the Islamic Republic’s Achilles’ heel. It is a social struggle. The battle against hijab is waged every day by ordinary women who go out without a headscarf. They find various ways to protest against the regime. The Islamic Republic created a secret police last year for the sole purpose of monitoring the hijab in the streets. So, for any meaningful change to take place there have to be movements at the grassroots level, and not just by women but by a larger segment of society. That may put pressure on the regime to lift hijab law. I doubt that it would ever happen but it isn’t impossible.

How do you view a recent move by Saudi Arabia to give women greater rights?

Frankly, I expected that. If you recall, a woman who had been accused of violating Islamic law was publicly beheaded in Saudi Arabia a few years ago. It was obvious that a lot was happening in that society. Women were very active in various fields in the 1920s in Iran. Reza Shah [the founder of Pahlavi dynasty] decreed kashf-e hijab [banning Islamic veils including the headscarf in 1936.]

It is obvious that a movement is forming in Saudi Arabia. I recently read that the Saudi Crown Prince [Mohammad bin Salman] plans to modernize the country. International pressure might have played a role in this decision. But more important is the critical role that industry and manufacturing plays in the growth of Saudi Arabia’s economy. We have witnessed the same trend in other Gulf states. With the exception of Bahrain, most other Persian Gulf states eased some of the restrictions on women.

I attended the International Women’s Conference in Beijing in1995. Women’s rights activists from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) had a booth at the convention. I asked them why they had hung a picture of the king in the booth. They explained that the kingdom had afforded them a rare opportunity to showcase their achievements, but that they still had to be cautious. So there has been some progress in the Gulf states.

But as I said earlier, international pressure has played a role in the changes that have occurred in Saudi Arabia. In an article, a Bahraini woman criticized Hillary Clinton for accepting $100,000 in campaign donations from Saudi Arabia. She questioned Secretary Clinton’s ethics for accepting money from a regime that allows 9-year-old girls to be given away in marriage, which is tantamount to child abuse, pedophilia, and rape. She challenged Mrs. Clinton’s feminist credentials. Women in North African countries such as Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia have been fighting for their rights for years. I believe all these developments have prompted the Saudi Kingdom to implement some reforms.