Ever since Israel launched a strike against the Iranian embassy in Damascus on April 1, killing seven people including two senior members of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, fears have mounted that Tehran would order a revenge attack against Israel. Bloodcurdling rhetoric from Iran’s leaders has done nothing to allay those fears, with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei declaring that Israel “must be punished and it shall be”. Meanwhile, the US president has promised Israel “ironclad” US support and vowed to “do all we can to protect Israel’s security”. So how worried should the west be? Could this escalate into a wider regional war? We spoke with Scott Lucas, a Middle East scholar at University College Dublin, who has been writing about tensions in the Middle East for many years.

1. What prompted Israel to launch its attack on Iran’s embassy in Damascus? Are they not busy enough in Gaza without the prospect of opening another front in the conflict?

Israel has been attacking the positions of Iran, an essential supporter of the Assad regime in Syria’s internal conflict, for more than a decade. They have periodically struck Iranian and Assad positions to disrupt the transfer of weapons and missiles to Lebanon’s Hezbollah, an Islamist militant organisation.

After the start of the war with Hamas on October 7, Israel shifted from attacks on munitions to targeted assassinations of senior Iranian officers. Iran’s top commander in Syria, Sayyed Razi Mousavi, was killed on December 25, and other commanders – including the Iranian head (Sadegh Omidzadeh) and deputy head (Hajj Gholam) of intelligence – were slain in Damascus in subsequent strikes.

The assassination of Gen Mohammad Reza Zahedi, the Quds Force commander overseeing Syria and Lebanon, and six other personnel on April 1 was thus far from unprecedented. What was distinctive was the location: the first Israeli assault on an Iranian diplomatic complex.

2: Iran’s leadership is known for issuing bloodcurdling statements – but are Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s threats intended more for a domestic audience and to reinforce its leadership in the region?

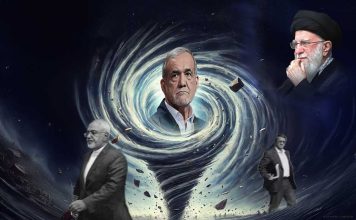

The threats of Khamenei, the Revolutionary Guards, and other Iranian officials are an essential projection of their image of strength, to both the domestic and overseas audience, to cover up the reality of the regime’s weakness.

But rhetoric is not action. When Iran tried the latter in January, it got punched in the nose. An escalation of strikes by Iranian-led militias in Syria and Iraq on bases with US personnel was halted by retaliatory US airstrikes. And a show of missiles across the Pakistani border backfired when Pakistan launched its own volley into south-east Iran.

3. Presumably the US and Israel know all this. How seriously are they taking this threat? Are we getting any clues from US or Israeli intelligence agencies?

Any threat from Iran has to be taken seriously, given the capability for attacks through its military, its proxies and its allies. Contingency plans will have long been in place in both the US and Israel.

The difference in recent days has been the publicity given to the threat by both the US and Israeli governments. That is a display to pre-empt or deter the Iranian regime.

Tehran reinforced the need for this display when it miscalculated with a blatant falsehood. Iranian officials said that the US asked them not to attack American personnel, implying that Washington would stand aside if the target was Israel. That raised the stakes for the US, including President Joe Biden, to reaffirm “ironclad” support for Israel.

4. Let’s presume Khamenei means what he says, and Iran is planning something big. What are Tehran’s options?

Iran has the capability for a direct assault on Israel with missiles. But this would inevitably bring Israeli and US strikes on Iranian territory – an exchange in which Tehran would be overmatched.

In theory, Hezbollah could launch that assault in the air and on the ground on the Israel–Lebanon border. But the Lebanese group, while skirmishing with the Israelis since October, is loathe to escalate a confrontation in which it could suffer serious damage.

Iran could return to encouraging militia attacks on the Americans in Syria and Iraq. However, this would be risky given the readiness of the US – already displayed in January – to hit the militias hard. An escalation by Yemen’s Houthi insurgents of attacks on Red Sea shipping could be checked by China, which has warned of the consequences for its economy.

Tehran has carried out cyberattacks in the past on entities in the US and Israel. While these have had some success, they would be unlikely to cause widespread disruption to the American and Israeli systems – both of which have cyber-warfare capabilities they have used against Iran in the past.

5. Failing an attack on Israel, what do you see as the most likely outcome in the short and medium term?

Soon after October 7, Iran’s regime assessed that its advantage over Israel was in the political and diplomatic realms. It could portray itself, alongside the civilians of Gaza, as the victim of aggression by Israel and the US.

That tactic has been reinforced since the attack on the Iranian consular building on April 1. While the supreme leader said this week that Israel “must be punished and it shall be”, his specific appeal was to Muslim countries to break economic and political ties with the Israelis. Iranian State and semi-official media – in contrast to the headlines in western media – have been counselling patience over Tehran’s response.

A short-term Iranian military response, bringing retribution upon Tehran, would probably undo this political and diplomatic approach. So the longer-term tactic is to try and build Iran’s connections with other countries in the region and beyond, while trying to disrupt Israel’s own connections. That would bring the victory of burying the “normalisation” between Israel and Arab countries, which has been the centrepiece of the Biden administration’s Middle Eastern strategy.