By Khalid Abdelaziz, Parisa Hafezi, Aidan Lewis

April 10 (Reuters) – A year into Sudan’s civil war, Iranian-made armed drones have helped the army turn the tide of the conflict, halting the progress of the rival paramilitary Rapid Support Force and regaining territory around the capital, a senior army source told Reuters.

Six Iranian sources, regional officials and diplomats – who, like the army source, asked not to be identified because of the sensitivity of the information – also told Reuters the military had acquired Iranian-made unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) over the past few months.

The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) used some older UAVs in the first months of the war alongside artillery batteries and fighter jets, but had little success in rooting out RSF fighters embedded in heavily populated neighbourhoods in Khartoum and other cities, more than a dozen Khartoum residents said.

In January, nine months after fighting erupted, much more effective drones began operating from the army’s Wadi Sayidna base to the north of Khartoum, according to five eyewitnesses living in the area.

The residents said the drones appeared to monitor RSF movements, target their positions, and pinpoint artillery strikes in Omdurman, one of three cities on the banks of the Nile that comprise the capital Khartoum.

“In recent weeks, the army has begun to use precise drones in military operations, which forced the RSF to flee from many areas and allowed the army to deploy forces on the ground,” said Mohamed Othman, a 59-year-old resident of Omdurman’s Al-Thawra district.

ANALYSIS: Iran’s Militia Networks in the Middle East and Africa

The extent and manner of the army’s deployment of Iranian UAVs in Omdurman and other areas has not been previously reported. Bloomberg and Sudanese media have reported the presence of Iranian drones in the country.

The senior Sudanese army source denied that the Iranian-made drones came directly from Iran, and declined to say how they were procured or how many the army had received. Sudan’s army had also developed Iranian drones previously produced under joint military programmes before the two countries cut ties in 2016, he added, without giving details. Reuters was unable to determine details about the drones independently.

The source that while diplomatic cooperation between Sudan and Iran had been restored last year, official military cooperation was still pending.

Asked about Iranian drones, Sudan’s acting foreign minister Ali Sadeq, who visited Iran last year and is aligned with the army, told Reuters: “Sudan did not obtain any weapons from Iran.”

The army’s media department and Iran‘s foreign ministry did not respond to requests for comment.

The RSF acknowledged it had suffered setbacks in Omdurman. Its media office said the army had received Iranian drones and other weapons, citing intelligence it had gathered. It did not respond to requests to provide evidence.

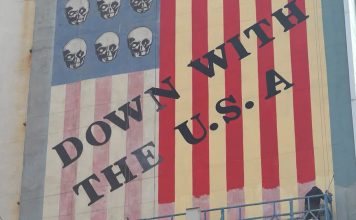

Tehran’s backing for Sudan’s army is aimed at strengthening ties with the strategically located country, the Iranian and regional sources said.

Sudan lies on the coast of the Red Sea, a key site of competition between global powers, including Iran, as war rages in the Middle East. From the other side of the Red Sea, Yemen’s Houthis, armed in part by Iran, have launched attacks in support of Hamas in Gaza.

“What does Iran get in return? They now have a staging post on the Red Sea and on the African side,” said a Western diplomat, who asked not to be named.

Iran Signs Economic Agreements With Zimbabwe as Raisi Ends Africa Tour

Recent territorial advances are the most significant for the army since the fighting began in Sudan’s capital last April.

The war, between army head General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and RSF head General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, has pushed millions into extreme hunger, created the world’s largest displacement crisis, and triggered waves of ethnically driven killings and sexual violence in the Darfur region of western Sudan.

U.N. experts have said the RSF war effort has been aided by backing via neighbouring African states including Chad, Libya and South Sudan, and that allegations of material support from the United Arab Emirates to the RSF were credible.

The army’s success in Omdurman allowed it from February to pursue similar attacks using drones, artillery and troops in Bahri, north of Khartoum, to try to take control of the key Al Jaili oil refinery, two witnesses there said.

The army has said that its recent gains have also been helped by recruitment – taking place over more than six months and accelerating since December – of thousands of volunteers in the areas it controls.

FLIGHTS FROM IRAN

Cooperation between Sudan and Iran was strong under former President Omar al-Bashir, until he turned to Iran‘s Gulf rivals for economic support late in his three-decade rule, cutting relations with Tehran.

Amin Mazajoub, a former Sudanese general, said Sudan had previously manufactured weapons with the help of Iran, and had repurposed drones already in its possession to make them more effective during the war. Mazajoub did not specifically comment on the source of the drones recently used in combat.

A regional source close to Iran‘s clerical rulers said Iranian Mohajer and Ababil drones had been transported to Sudan several times since late last year by Iran‘s Qeshm Fars Air. Mohajer and Ababil drones are made by companies operating under Iran‘s Ministry of Defence, which did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

Flight tracking records collated by Wim Zwijnenburg of Dutch peace organisation Pax and provided to Reuters show that in December 2023 and January 2024, a Boeing 747-200 cargo plane operated by Qeshm Fars Air made six journeys from Iran to Port Sudan, an important base for the army since the RSF took over strategic sites in Khartoum in the first days of the war.

The frequency of these flights has not been previously reported. Emails and phone calls to Qeshm Fars Air, which is under U.S. sanctions, went unanswered. Reuters was unable to establish whether the details listed for the airline were up to date.

A photo provided by satellite imaging company Planet Labs for which Reuters verified the location and date, shows a Boeing 747 with the wingspan consistent with a 747-200 at Port Sudan airport on Dec. 7, the date of the first of the tracked flights, Zwijnenburg said.

A Mohajer-6 appeared in January on the runway at the Wadi Sayidna base in another satellite photograph dated Jan. 9, Zwijnenburg said.

The RSF said the army was receiving twice-weekly cargo plane deliveries of Iranian drones and other arms from Iran. It told Reuters that RSF intelligence showed deliveries of Iranian Mohajer-4, Mohajer-6 and Ababil drones to Port Sudan. It said it had shot down several of the drones.

The RSF did not provide evidence for the drone deliveries.

Sourcing weapons from Iran could complicate relations for the Sudanese military with the United States, which is leading a push for negotiations between the warring parties.

U.S. Special Envoy for Sudan Tom Perriello said in an interview on Wednesday that fear of greater influence for Iran or Islamic extremist elements in Sudan was one reason the U.S. believed there was momentum for a peace deal.

A U.S. State Department spokesperson said the U.S. had seen the reports on Iranian support for the army and was monitoring the situation.

“The United States opposes external involvement to support the Sudan conflict – it will only exacerbate and prolong the conflict and risks further spreading regional instability,” the spokesperson said.

(Additional reporting by Daphne Psaledakis and Alexander Cornwell; Writing by Michael Georgy and Aidan Lewis; Editing by Frank Jack Daniel and Daniel Wallis)