By Timour Azhari and Ahmed Rasheed

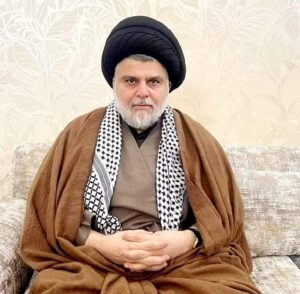

NAJAF, Iraq, May 12 (Reuters) – Powerful Iraqi Shi’ite Muslim cleric Moqtada al-Sadr is laying the groundwork for a political comeback two years after a failed and ultimately deadly high-stakes move to form a government without his Shi’ite rivals, multiple sources said.

His return, likely planned for the 2025 parliamentary election, could threaten the growing clout of rivals including Iraqi Shi’ite parties and armed factions close to Iran, and undermine Iraq’s recent relative stability, observers say.

However, many among Iraqi’s majority Shi’ite population are likely to welcome Sadr’s re-emergence, especially his masses of mostly pious and poor followers who view him as a champion of the downtrodden.

ANALYSIS -Iraq’s Competing Shi’Ite Groups and Their Links to Iran’s Regime

Reuters spoke to more than 20 people for this story, including Shi’ite politicians in Sadr’s movement and in rival factions, clerics and politicians in the Shi’ite holy city of Najaf, and government officials and analysts. Most spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters.

“This time, the Sadrist movement has stronger plans than the last time round to win more seats in order to form a majority government,” a former Sadrist lawmaker said, though the final decision to run has not officially been made.

Sadr won the 2021 parliamentary election but ordered his lawmakers to resign, then announced a “final withdrawal” from politics the next year after rival Shi’ite parties thwarted his attempt to form a majority government solely with Kurdish and Sunni Muslim parties.

A dominant figure in Iraq since the 2003 U.S.-led invasion, self-styled nationalist Sadr has railed against the influence of both Iran and the United States in Iraq.

Iran views Sadr’s participation in politics as important to maintaining Iraq’s Shi’ite-dominated political system in the long term, though Tehran rejects his aspirations to be recognised as its single most dominant force.

The United States, which fought Sadr’s forces after he declared a holy war against them in 2004, sees him as a threat to Iraq’s fragile stability, but also views him as a needed counter to Iranian influence.

Many Iraqis say they have lost out no matter who is in power while elites siphon off the country’s oil wealth.

CLERICAL NOD

Since March, Sadr has stepped back towards the limelight.

First, he held a rare meeting with Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, a prominent cleric revered by millions of Shi’ites who played a central role in ending the deadly intra-Shi’ite clashes in 2022 that preceded Sadr’s political exit.

Sadrists interpret the March 18 audience with Sistani, who stays above the fray of Iraq’s fractious politics and does not typically meet politicians, as a tacit endorsement, according to six people in Sadr’s movement.

A cleric close to Sistani said Sadr spoke about a possible return to political life and parliament and “left this important meeting with a positive outcome”. Sistani’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Days after the meeting, Sadr instructed his lawmakers who resigned in 2021 to gather and re-engage with the movement’s political base.

He then renamed his organisation the Shi’ite National Movement, a swipe at rival Shi’ite factions he deems unpatriotic and beholden to Iran as well as a bid to further mobilise his base along sectarian lines, a person close to Sadr said.

While some analysts fear the disruption of a Sadr return to frontline politics, others say he could re-emerge humbled by the routing of his forces during the intra-Shi’ite strife as well as the relative success of the current Baghdad government, including its balancing of relations between Iran and the U.S.

“Of course, there is always a greater risk of instability when you have more groups balancing power, especially when they are armed. But the Sadrists should return less hostile,” said Hamzeh Hadad, an Iraqi analyst and visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“The political parties know it’s best to share power than to lose it all together,” he said.

A senior Sadrist politician said the movement might seek to ally with some ruling Shi’ite factions, such as popular Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani, while isolating others including arch-rival Qais Al-Khazaali, leader of the powerful, Iran-backed political and military group Asaib Ahl al-Haq.

Advisers to Sudani said he was keeping his options open.

“There are groups in the framework that we have long-time relations with and could ally with before or after elections. What we don’t accept is to get into deals with corrupt militias,” the senior Sadrist said.

In Sadr City, Sadr’s sprawling, long-impoverished stronghold on the east side of Baghdad, many supporters await his return in the hope this could translate into jobs and services.

“This city supports Sadr and I don’t think he would forget us after all the sacrifices we have made for him,” said Taleb Muhawi, a 37-year-old father of three who was waiting to hear back on a government job.

“He needs to shake things up when he comes back.”

(Reporting by Ahmed Rasheed and Timour Azhari; writing by Timour Azhari; editing by Mark Heinrich)