[aesop_content color=”#ffffff” background=”#333333″ columns=”1″ position=”none” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” disable_bgshading=”off” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”up” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off” aesop-generator-content=”Disclaimer: This asset – including all text, audio and imagery – is provided by The Conversation. Reuters Connect has not verified or endorsed the material, which is being made available to professional media customers to facilitate the free flow of global news and information.

“]Disclaimer: This asset – including all text, audio and imagery – is provided by The Conversation. Reuters Connect has not verified or endorsed the material, which is being made available to professional media customers to facilitate the free flow of global news and information.[/aesop_content]

After more than four decades as seemingly implacable enemies on either side of a deep political-religious divide in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia and Iran have agreed to restore diplomatic relations and reopen embassies. The deal, which was signed in Beijing, comes seven years after diplomatic relations were severed in the aftermath of the execution in Saudi Arabia of Shia cleric Nimr Al Nimr and has been heralded as a “game-changing moment” for the Middle East.

While undeniably a positive move, the agreement will not end conflict in the region – with serious domestic issues continuing to drive conflict and violence in Yemen, Iraq, Lebanon and Syria. Yet serious economic challenges have prompted the Saudis and Iranians to engage in diplomatic talks over the past few years to create a more stable regional order, allowing their countries to engage in domestic reform programmes as a result.

The rivalry between Riyadh and Tehran has fractious roots, shaped by the interplay of security concerns, claims to leadership over the Muslim world, ethno-sectarian rivalries, and differing relationships with Washington. Lazy analysis has often reduced the rivalry to a sectarian conflict, a consequence of “ancient hatreds”. But such a reading of events is xenophobic and orientalist and ignores the context and contingencies shaping relations between the two states.

Despite the fractious roots, relations between the two states have oscillated between overt hostility and burgeoning detente since the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979, playing out in different ways across the Middle East.

The presence of shared religious, ethnic and ideological identities across the region has also prompted others to view conflict across the region through the lens of “proxy wars”. Various groups in Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Bahrain and elsewhere have been seen as merely doing the bidding of paymasters in Riyadh or Tehran. This ignores the internal drivers of conflict and division, reducing analysis to a simplistic binary pitting Sunni against Shia.

Across the region, states where Saudi and Iranian interests have clashed, have also been beset by a range of their own complex socioeconomic and political challenges.

Since Saddam Hussein was deposed, Iraq has been characterised by a struggle among various factions to dominate the state. Shia parties, representing the country’s majority, have typically won elections, often with the support of Iran and much to the chagrin of Saudi Arabia. Yet to think of Iraqi politics purely as representing a proxy war between its two neighbours would be wrong. It ignores the domestic concerns of many and efforts to create a political landscape that works for Iraqis and is not just an arena for Riyadh and Tehran to increase their power.

In Yemen, while Saudi Arabia and Iran have both played a prominent role in the civil war, the key drivers of conflict are domestic, amid a broader struggle over territory, politics, visions of order, tribalism, resources and sectarian difference. The involvement of Riyadh and Tehran – in different ways – exacerbates these tensions. Fears about gains by Iran-backed Houthi rebels across Yemen prompted Saudi Arabia to embark on a devastating bombing campaign to curtail the group’s actions.

OPINION: The Solution to the ‘Iran Problem’ is Regime Change

Tehran’s support for the Houthis – and the group’s attacks on the Saudi mainland – exacerbated the kingdom’s fears. Yet the war in Yemen is also a consequence of the fragmentation of the state and the emergence of several different groups vying for influence across a landscape beset by serious environmental challenges and food shortages.

In Lebanon, a devastating socioeconomic crisis plays out in the shell of the state, with sectarian groups providing support and protection to their constituencies in place of a functioning government. Key groups have received support from Saudi Arabia and Iran – most notably Hezbollah, which possesses strong ideological links with the Islamic Republic, and the Future Movement the party of government across most of the past decade, which has a complex relationship with Saudi Arabia.

Clearly the Saudis and Iranians have a keen interest in Lebanese politics. But in reality any conflict here is driven by competition between local groups seeking to impose their visions of order on a precarious political, social and economic landscape.

While there is little doubt that Saudi Arabia and Iran have the means to exert influence on politics across the region, local groups have their own agendas, aspirations and pressures. It remains to be seen how the reconciliation between Riyadh and Tehran will resonate in spaces beset by division.

There are undeniably positives for regional security. The reconciliation improves the possibility of a revived nuclear deal with Tehran – although it remains to be seen what Saudi Arabia has offered Iran to facilitate the agreement, and vice versa. Also, there are questions as to what monitoring and enforcement mechanisms have been put in place by China.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of all of this concerns China’s role in proceedings. While diplomatic efforts aimed at improving relations between the two rivals have been taking place for several years, China’s ability to forge an agreement out of these talks points to Beijing’s growing influence in the region.

China has long had close economic ties with Iran, but in recent years Beijing has sought to increase its engagement with Arab states, notably Iraq and Saudi Arabia. Deteriorating relations between the two major Gulf powers would have had a negative impact on Chinese engagement and investment across the Middle East, both in terms of its infrastructure projects and the broader Belt and Road Initiative.

Although the US has publicly celebrated the initiative, privately there are several concerns about the broader implications for the Middle East and for global politics. This comes at a time when relations between Riyadh and Washington are tense.

This was perhaps best seen in the visit of the US president, Joe Biden, to Saudi Arabia after his vocal criticism of the kingdom’s human rights record and the publication of a report stating that Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman approved the operation to kill journalist Jamal Khashoggi, a US citizen. During the visit, Biden and bin Salman endured a tense meeting which largely failed to improve relations and highlighted the precarious nature of relations.

In such an environment, rising Chinese influence in the kingdom and across the Middle East is hardly surprising. China’s move into mediation offers some semblance of hope that an agreement can also be reached to end the war in Ukraine, but at what cost? The Chinese model of investment and the provision of “untied aid” – the provision of financial support without conditions – has long ignored concerns about democracy and human rights. So the agreement between the Saudis and the Iranians has been read by some as a victory for authoritarianism, further marginalising reform movements in both countries.

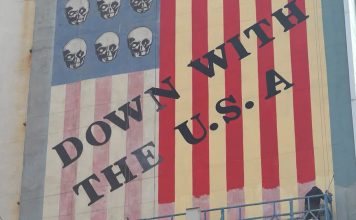

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/2016-01-03T120000Z_241627589_GF10000281570_RTRMADP_3_SAUDI-SECURITY-IRAN.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”FILE PHOTO: During a state sponsored demonstration against the execution of Nimr in Saudi Arabia, outside the Saudi Arabian Embassy in Tehran, a protester holds up a street sign with the name of Shi’ite cleric Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr. REUTERS” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Much like the US, Israel is also concerned about the deal. For successive Israeli governments, Iran has long occupied the role of regional

bete noire, ultimately feeding into the signing of the Abraham Accords in the summer of 2020 which normalised relations between Israel, the UEA, Bahrain and Morocco as a strategic alliance against Tehran. The Netanyahu government has long sought to normalise relations with Saudi Arabia and hoped to use the Iranian threat as a means of achieving this goal.

Additionally, the deal raises questions about the future of regional security. The US has long been a mediator in regional disputes and has been viewed as a security guarantor by Israel, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. China’s actions here suggest that it is seeking to assert itself more keenly in the region’s politics. Reports suggest that Beijing is to host a meeting of Arab and Iranian leaders later in the year. If accurate, it positions China firmly as a – if not the – dominant actor across the Middle East.

A reconciliation between the Saudis and the Iranians is certainly good for regional order. But it will not address the causes of conflict in Yemen or elsewhere across the region. It also raises several serious issues around regional security and global order, the salience of democracy and human rights, and the future of US engagement with the Middle East.

While the initiative is a positive step, it is not a solution for the region’s conflicts. This Beijing-mediated agreement may in fact lead to further significant challenges for the people of the region.