By Elahe Boghrat

Editor-in-chief, Kayhan-London

While studying at the Department of Political and Social Sciences of Berlin University, I took a course in Karl Marx’s “Das Kapital” (published in 1867.) I always knew that the ideas presented in the book were intellectually challenging. So I figured that if the Farsi translation of the text were hard to understand, then the original German would be next to impossible to comprehend.

To prepare myself for the course I bought a Farsi translation of the book by Iraj Eskandari (1908-85), a former member of the Iranian Parliament (1944-46), Minister of Trade, Crafts and Arts (1946) and Secretary of the Iranian Tudeh (Communist) Party (1969-1978.) In the foreword to the book, Mr. Eskandari writes that he compared multiple translations of the book in various languages to ensure that the Farsi version maintained the thrust and integrity of the original text.

However, the more I read the Farsi version of the “Das Kapital,” the less I grasped its meaning. I eventually discovered that the original German text was much easier to understand because the language and the ideas in the book were parts of the same social, cultural and intellectual environment. It is, therefore, no wonder that the Farsi version should be awkward and difficult to understand, because the ideas, the culture, the mindset, and the language are alien to us. In other words, we have imported them. That is why Marx’s ideas were somewhat more accessible to me in the original German than in Farsi, which is my native language.

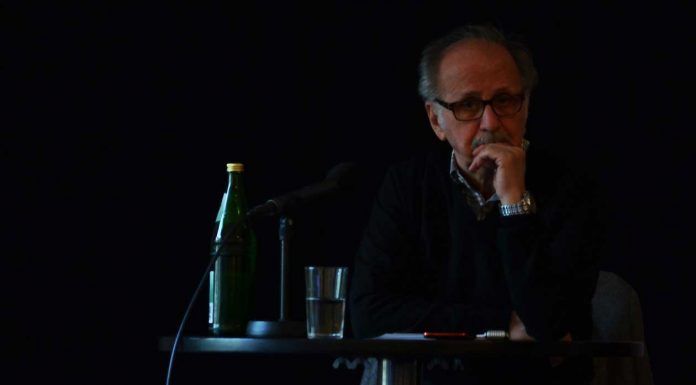

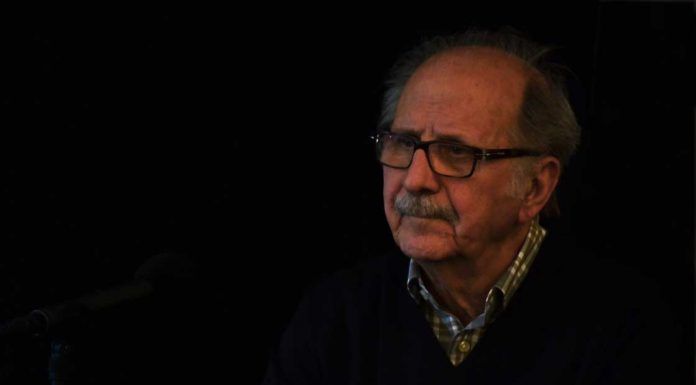

Iranian philosopher, author, and former Tehran University lecturer Aramesh Doostdar (also spelled Dustdar, born in 1932) has discussed this issue extensively in his latest book “Language and Pseudo-Language, Culture and Pseudo-Culture.”

Mr. Doostdar labels imported language and culture which lack authenticity as pseudo-language (quasi-language) and pseudo-culture (quasi-culture), respectively. He has described the book as “the last arrow in his intellectual bow.”

Doostdar says that efforts to translate works by foreign authors began when we entered the modern era. “Our language and culture during this so-called modern era compared to the traditional period preceding it could be described as pseudo-language and pseudo-culture,” Doostdar explains. “Our language and customs were born out of authentic and deeply-rooted traditions. They were products of a particular mindset, culture, and religion with Islam as its principal ingredient.”

The “Language and Pseudo-Language, Culture and Pseudo-Culture” consists of seven chapters. Doostdar starts the book with his usual stinging and visceral style. “Nothing is so close and yet so far from us as our language. Close, because it is an integral part of everything we do in the world. We even speak to ourselves when we sit in silence. It is at the same time remote, because Islamic education has consistently diminished its influence all throughout our history. We know this to be true if we think about it carefully,” Doostdar says.

Doostdar explains: “Western culture is an organism which consists of many parts. We cannot, therefore, contemplate various aspects of this complex organism which is completely alien to us. We are outside, trying to get a glimpse of what is inside. We think that we are contemplating and reflecting on these ideas that are fundamentally foreign to us. We only regurgitate ideas and delude ourselves into believing that we are thinking. No one wants to admit or face this fact.”

Doostdar points out that we cannot and should not underestimate the influence of Islam on every aspect of our lives. He notes: “Islam is not merely a missing link in the historical chain that defines who and what we are. Islam has shaped our individual and collective identities.”

Anger rather than hatred motivates Doostdar, who believes that to awaken our national consciousness we must adopt the same treatment used by Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), which enables addicts to come out of their denials, own their lives, get sober and help others achieve sobriety.

We must accept the fact that in today’s Iran even atheists are culturally Muslim. Doostdar calls this phenomenon“religious tendency.” By religion, Doostdar doesn’t mean only Islam, but people who blindly follow and emulate a source without question. Religion and creed prohibit people from exercising their critical judgment. They have ready-made answers to dispel doubts and discourage any attempts to challenge neatly fabricated explanations. So, the situation begs the question: “How has the Islamic Republic been able to suppress the noble Iranian spirit that espouses good thoughts, good words, and good deeds?”

Doostdar says: “Cultures and ideas cannot progress beyond the boundaries set by their respective indigenous languages. Those who insist on writing in the so-called pure Farsi cannot distance themselves from their deep-rooted Islamic tradition. They are unable to think in pure Farsi.”

Doostdar explains: “We were beginning to understand our role as citizens under the late Shah’s rule. We were developing our civil, judicial and economic institutions. We were starting to grasp the meaning of the rule of law, security and individual freedom. We understood the significance of these changes but didn’t comprehend their implications. There is a difference between understanding an idea and comprehending its impact. Only when an idea has become clear to us, and we understand it completely, do we comprehend it. There are only a handful of people who truly comprehend the true harm that the Islamic Revolution has inflicted on the Iranian culture and nation.”

I’ve always been amazed by how a beautifully written piece can be completely incomprehensible. Doostdar says: “A writer mistakenly believes that his private language has become universal when he uses it to address the public. He believes that others do or should comprehend his language.”

Doostdar argues that language dictates how we humans think. I, however, cannot entirely agree, because in my view thoughts quantify and frame a language. A language reflects the inherent flaws and limitations of a particular intellectual process. There are many occasions for instance when we understand the meaning of a word in a foreign language but cannot find its equivalent in Farsi. So, our language does not restrict our intellect and understanding.

We should, therefore, be able to overcome the culture that history has forced down our throat. Doostdar has always been able to do just that. Poor translations of the “Das Kapital” or other foreign ideas is not due to our intellectual limitations but linguistic restrictions.

Doostdar points out: “A language erects boundaries around ideas. In the same way, a culture restricts the sphere of influence of a language. Language limits intellect and culture restricts language.”

One can, however, argue that there are no linguistic constraints on ideas and intellectual processes; unless we are discussing a particular sphere of thoughts such as social and political ideas.

Translated from Persian by Fardine Hamidi

“Language and Pseudo-Language, Culture and Pseudo-Culture”

By Aramesh Doostdar

First Printing: Forough Publishing, Cologne (Koln), Germany

Spring 2018