The Iranian artist Monir Farmanfarmaian, who produced stunning mirror works inspired by an ancient Iranian tradition, has died at the age of 97.

The charismatic, silver-haired artist got her first career survey at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in March 2015, at the age of 91. By then, she was based in Tehran after years spent in the United States.

Monir first lived in New York as an art student, and later, after the Iranian Revolution, as a budding artist. She spent a total of 12 years of her life in the city.

While in New York, she met Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. She befriended Andy Warhol, made mirrored disco balls for him, and subsequently received one of his Marilyn Monroe portraits.

Returning to Iran before the Revolution, she entertained in style at the Tehran villa that she shared with her husband Abolbashar Farmanfarmaian, a lawyer and investor, and their children.

Her love of mirror work originated during an early 1970s visit with the American artist Robert Morris to the Shah Cheragh Mosque in Shiraz, as she recalled in “Monir,” an hour-long documentary released in 2014 that was directed by Bahman Kiarostami (son of the late filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami) and produced by the London-based Iranian curator Leyla Fakhr.

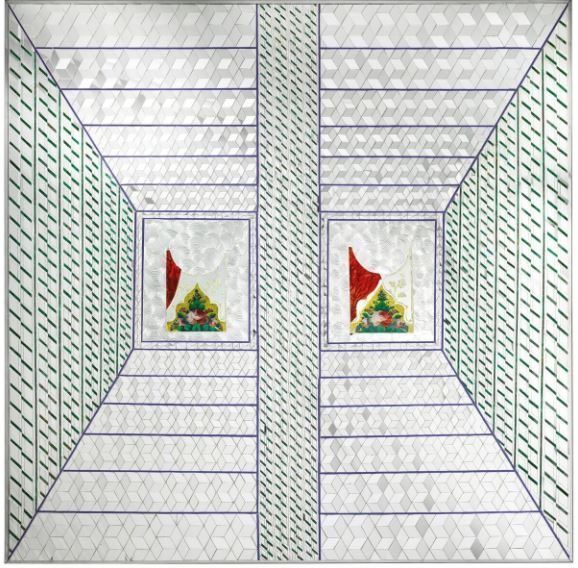

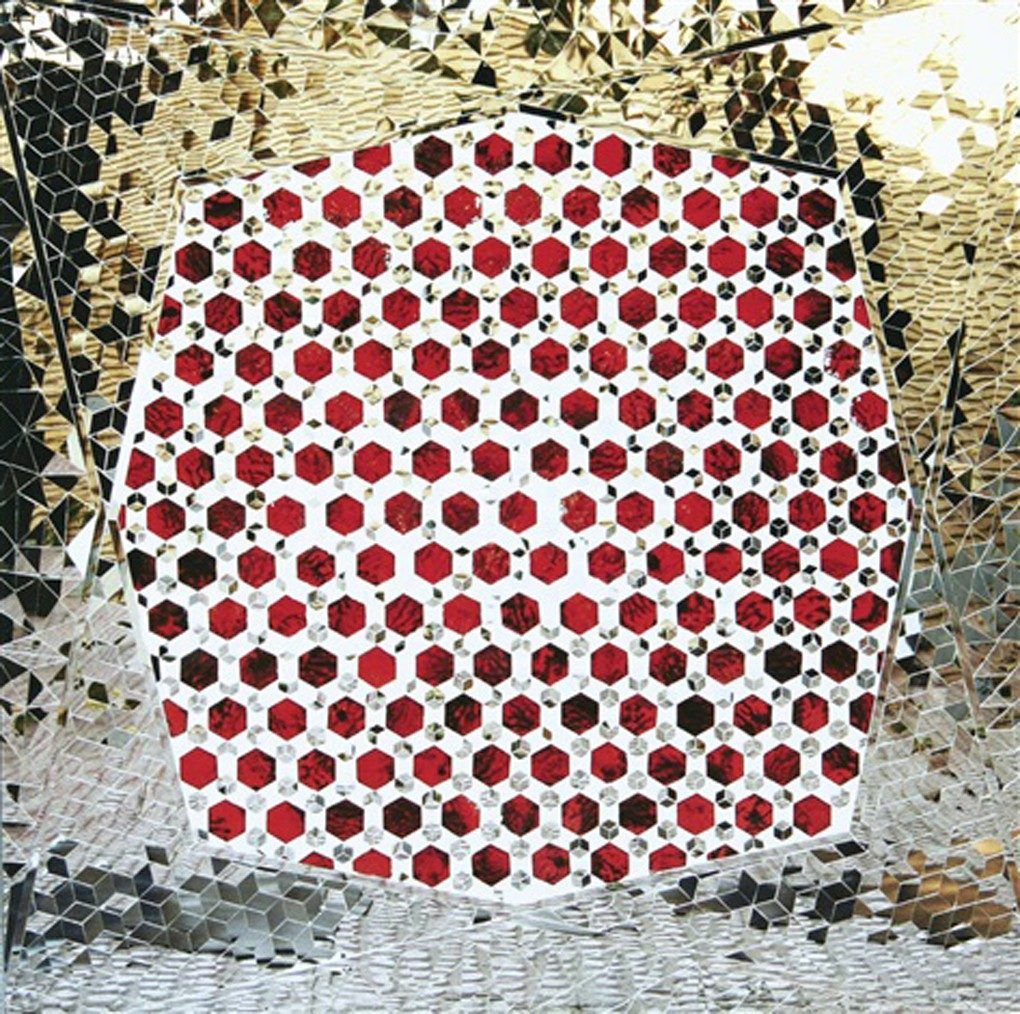

The interiors of the Shah Cheragh mosque, she recalled in the film, were entirely covered with carved mirror fragments that sparkled like diamonds and reflected the hundreds of worshipers gathered there.

Monir secretly wished she could cut a piece of the mirror work off the wall and take it home for her own private contemplation. So she decided to make her own, and invented a very personal art form in the process.

Her mirror works are stand-alone sculptures, rather than elaborate elements of interior decoration, and are based on meticulous geometric designs that she produces herself.

The film portrays her as a straight-talking, no-nonsense lady with a deadpan sense of humor. When she’s not busy quibbling with the master craftsmen who help her execute the metal and mirror work for her sculptures, she playfully scolds the director for filming her too much.

The idea for the movie came to Fakhr several years ago, when she discovered that there was little documentation on Iranian art of the 1960s and 1970s. She set out to make a film about Monir, unaware that the Guggenheim was planning a major exhibition.

To direct the film, she approached the younger Kiarostami, a documentary filmmaker interested in the arts, culture and music of today’s Iran. Kiarostami, who had recently completed a documentary on the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, was surprised that no film had yet been made about Monir, and immediately said yes.

The artist herself was infinitely more difficult to persuade. “It was very hard [for her] to believe that we were very serious in what we did,” Fakhr recalled.

That reluctance creates a comical tug-of-war between filmmaker and subject. From the opening credits, Monir asks to be kept off screen. “Please don’t point your camera at me, it scares me!” she begs Kiarostami, who replies (off camera) that either he continues filming, or there will be no film.

There are moments of pathos, too. She recalls how the death of her husband in 1991 led her to stay shuttered at home for a year. She revisits her former home in Tehran, now an abandoned residence, and sits silently by the empty swimming pool in one of the film’s most touching moments.

Plenty of curators and critics are interviewed in the documentary, notably the American abstract artist Frank Stella. He recalls how difficult it was for Monir to focus on her art while raising children, and explains that it was her post-revolutionary move to New York that made her the artist she is today. She was then able to “find herself and find a way of working with the visual culture she came from.”