By Nazanine Nouri

Shadi Ghadirian is one of four Iranian photographers featured in a major exhibition at Berlin’s Pergamonmuseum, one of the city’s main attractions.

The works by Ghadirian, Arman Stepanian, Najaf Shokri, and Taraneh Hemami are in dialogue with historical objects from the collection at the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin. “Capturing Iran’s Past Fotokunst – PhotoArt” includes four photo series and a mirror installation.

The Pergamon, located on Museum Island in Berlin, houses three museums in one – the Collection of Classical Antiquities, the Museum of the Ancient Near East, and the Museum of Islamic Art.

Using different visual methods, the Iranian artists in the exhibition reference a variety of periods in Iran’s past — from the beginnings of photography in 1842 all the way up to the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88).

“Their imagery treats the past as a foil for comparison, in order to question it on several levels through metaphors and allegories, and draw on it to make statements about the present,” said the Pergamon.

Shadi Ghadirian is considered one of the first women to have revolutionized contemporary photography in Iran. Her work is mainly concerned with contemporary female Iranian identity within traditional settings, contrasting the conservative roles attributed to women in society with the impact of modernity.

Her photos capture women’s lives behind closed doors, as they are caught between tradition and modernity, past and present, east and west, public and private, reality and fantasy. Her Qajar series (1998), on display at the exhibition, restages studio portraits from the time of the Qajar dynasty (1779-1925) with an added contemporary elements. Each portrait includes a subversive, often Western, prop, such as a Pepsi can, sunglasses, a boom box or a vacuum cleaner.

Ghadirian was born in Tehran in 1974 and was among the first to graduate from Azad University with a BA in photography. Working at Tehran’s Museum of Photography while studying for her degree, she was fascinated by Nasser al-Din Shah’s pictures of his many wives, dressed up in Iranian versions of the tutu, which he had discovered after a trip to the ballet in Paris. (The Persian monarch introduced photography to the country after coming across it in his travels to Europe in the 19th century.)

Ghadirian started working on a project inspired by the photographs, using her sisters, cousins and friends as models, and borrowing old historical backdrops from the museum and period costumes from a TV wardrobe department. She portrayed women, each posing with a symbol of modern life while wearing traditional Iranian dress.

“This conflict between old and newis how the younger generation are currently living in Iran: we may embrace modernity, but we’re still in love with our country’s traditions,” she told The Guardian in a 2013 interview.

The artist said she hoped that when people saw her photographs, they would “understand the reality for women in Iran, then and now.”

Decades after the end of the Iran-Iraq War, Ghadirian also reflects on the trauma for people who experienced the war. Her “Nil Nil” series (2008) juxtaposes everyday items with objects related to war, concealing these objects in seemingly idyllic interior spaces — such as the grenade nestled between the apples and oranges in a fruit bowl.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/01_ISL_CTP_Ghadirian_Nil-Nil-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”aus der Serie Qajar, 1998, © Silk Road Gallery / Shadi Ghadirian” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Ghadirian, whose work has been shown at the British Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, continues to live and work in Iran.

In his “Gravestones” (1999-2000) and “Doorbells,” (2004) Arman Stepanian places portraits from the Qajar and Pahlavi dynasties in contemporary scenery – a reminder that the conditions of our present were shaped by our forefathers.

In his “Gravestones” series, weathered photographs of deceased Iranian Christians are framed by the distressed surfaces of gravestones. The artist started work on this series after gravestone photos caught his eye while visiting his father’s grave in the Armenian cemetery. He wondered what they were thinking or how happy they were when they were getting ready to pose for the photo. Did they ever imagine that some day that same photo would be placed on their gravestone?

Arman Stepanian, who lives and works in Tehran, is an Armenian-Iranian artist born in Abadan in 1956. He was behind the “Armenian-Iranians seen in Camera” exhibition held at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in 1990. He also participated in “Iran inside out” at New York’s Chelsea Art Museum in 2009,

Taraneh Hemami’s “Hall of Reflections” (2000-12) uses mirrors and glass as surfaces on which to display images and text that present a broken map of Iranian migration, displacement, and assimilation. Transforming photographs and letters from Iranian emigres to the US into mirror assemblages, she the pain caused by the sense of not belonging, displacement and loss of a place that is now a thing of the past.

“Hall of Reflections” traces the scattered memories and migrations of Iranians in the second half of the 20th century to the place where they live now, the San Francisco Bay Area. It is at once art, history, archive, and, as the name suggests, reflection. The installation of the many mirrors is physically and conceptually designed to piece together the fragmented stories of Iranian immigrants, exiles and second-generation Iranian-Americans.

“For the past 24 years, I have lived with the images and representations of Iranians in the media here in the US,” she recalls in remarks published by Iranian.com. These are “potent images painting a false and altered reality of my people for the American audience, yet so strong that they have at times influenced my perception of who we are.”

“Part of what I had in mind in doing this project,” she adds, “was to create some kind of documented history of our community and to preserve it for the future generations.”

Hemami was born in Tehran in 1960 and moved to the United States in 1978 to study art at the University of Oregon. Though she had initially intended to return to Iran after completing her studies, she stayed on after the Iranian Revolution.

She is currently participating in the Market Street poster series, a public art series on display in San Francisco that examines Market Street as a place of gathering for protests and celebrations. She is also creating a public art project for the city of Oakland, looking at the symbol of the oak tree with a sculpture of reflective stainless steel and glass which should be completed by January 2020.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/05_ISL_CTP_Hemami_Hall_of_Reflections-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”aus der Serie Doorbells (2004), © Afrand Galerie / Arman Stepanian” align=”center” lightbox=”off” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

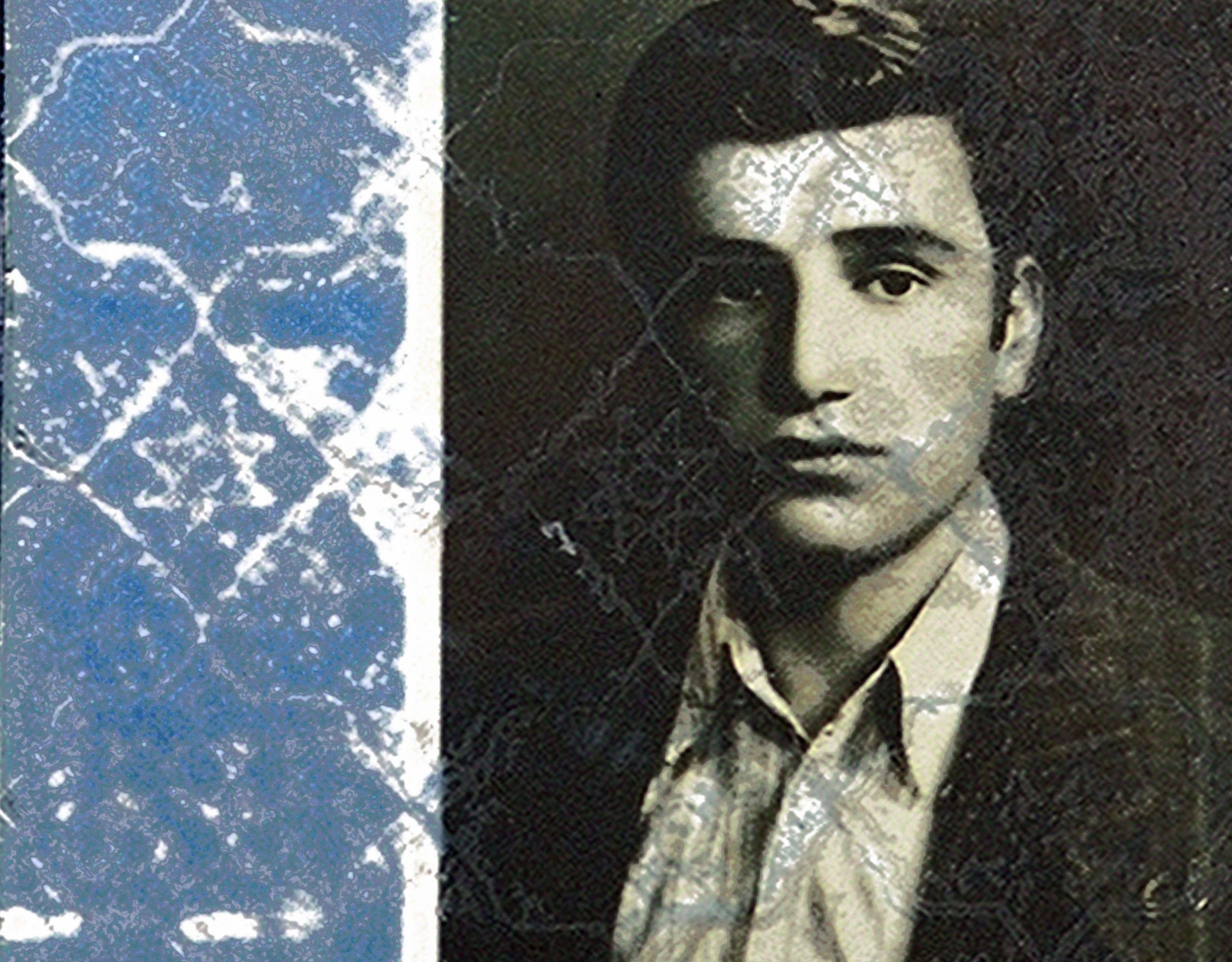

Najaf Shokri’s “Irandokht” (2006) and “The Registration Congregation of Iranian Men” (2006-12) appropriate found images. Scanning passport photographs from the Pahlavi era, the artist reveals no names or personal information. His ID portraits no longer focus on specific individuals but to what is now referred to as “meta-data” –postures in front of the camera, photographic style of the time, outfits, hairdos, makeup, etc.

Shokri made an intriguing discovery on his way to work in the fall of 2005, in a trash can outside a branch of the National Civil Registrations Organization near his house in downtown Tehran. The can was filled with old national IDs, all issued in 1942.

“It was like discovering a mass grave,” Shokri recalled in a 2013 Guardian interview. “They could have gone away and faded into history with no remaining trace.”

He decided to transform them into public heritage, and created an art project — a collection of ID photographs documenting a generation — which he called ‘Irandokht,’ meaning “daughter of Iran,” after noticing many women with that name among the documents. ‘Irandokht,’ a common first name in Iran at one time, is out of fashion today, which is in part why it was chosen by Shokri for his project.

Before being replaced with more modern ID cards, Iranian identification documents consisted of four-page birth certificates issued without photographs. The holder was required to add a photograph to the document before using it. Though all of the ID cards that Shokri found were issued in 1942, the images are drawn from the period between the late 1950s and late 1970s, when women had added their photographs to their IDs. This was a period when women’s roles in society changed dramatically, with women from a variety of backgrounds finding their way into schools and the job market, and removing their hijab in cities, or never wearing them.

“One can see the history of the era in these faces,” said Shokri. “Many of these women had mothers who were born to rural or small-town families but were married to men who came from the cities. The urban population was expanding and life was changing. It seems despite the fact that many of these families came from more traditional backgrounds, they were in the process of adapting to the more Westernized life of the big cities.”

Shokri was born in 1980 in Delfan, Iran, and started his artistic career in theater, writing short single-actor dramas and contributing to several theatrical groups. He lives and works in Tehran, teaching photography and occasionally writing plays.

“Capturing Iran’s Past Fotokunst -PhotoArt” runs through January 26.