In February of this year the United Nations confirmed a grim truth: Iran was sentencing more children to death than any other country in the world.

Far from being an anomaly, the recent surge in child executions in the country represents a renewed attempt at restoring order within an increasingly disillusioned, and disruptive, society. Empowered by Islamic jurisprudence to execute men, women and children where justice demands it, Iran’s government appears to relish the international community’s reaction to photos of children hanging from its gallows.

But does Sharia Law actually condone child execution?

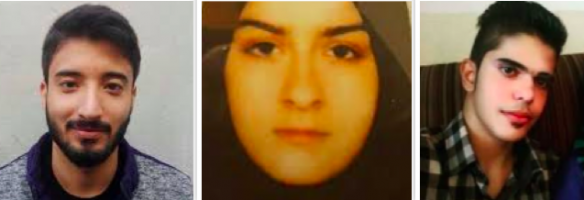

In January, Iran executed two boys and a girl. Amirhossein Pourjafar was accused of raping and murdering a three year old girl when he was eighteen. His lawyer told the court that Amirhossein experienced mental health difficulties, and had been hospitalized in a mental health centre during his detention. Ali Kazemi was charged with murder when he was fifteen, and then later executed at Bushehr prison, where Mahboubeh Mofidi was also executed, for murdering her husband at the age of seventeen. Mahboubeh was thirteen when she got married.

The media outlets that reported the stories offered limited accounts of these children’s crimes and their backgrounds, restricted by the Iranian government’s closed court system and its lack of willingness to share information. The opaque way in which the judiciary conducts its trials makes it almost impossible to discover important details about cases like these. Details which could explain the commission of these crimes, like self defence and mental illness.

Amnesty International released global figures on the use of the death penalty in April, and ranked Iran second only to China, for executing its citizens. Today, capital punishment has been largely abolished around the world. Iran’s use of the death penalty for minors places it within an even smaller group of countries. Amnesty’s report estimates that 92 children are currently on death row in Iran, though the number is likely to be much higher. Despite postponements and retrials, children on death row consistently find their death sentences renewed through the use of arbitrary processes lacking in structure and fairness. Children who demonstrate peacefully, or verbalise disagreement with their living conditions, can find themselves in prison for undefined offences, including “insulting the Prophet”, or “spreading corruption on Earth”.

The international community’s outrage over child executions in Iran has tended to focus on the idea that the Iranian government has breached its obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child (“the Convention”), which it signed in 1991, and ratified in 1994. The Convention bans the use of the death penalty for individuals convicted of crimes committed when they were under the age of 18. However, Iran’s heads of state signed the Convention with an added Reservation, allowing them to override the Convention if there was a conflict between it, and Islamic laws and values.

It is tempting to look at the phenomenon of child executions in Iran as an Islamic construct, but the truth is less controversial, and is more about quality of interpretation. Debate over whether Sharia Law allows child executions is growing. Some Muslim jurists insist that jurisprudence favours restitution over execution, and both the Sunni and Shi‘a schools of Sharia law hold that retaliation should not be carried out until the relatives of the victim are fully informed that an execution represents an aggression on a human soul and in turn, an aggression towards God.

Whilst the Quran enforces the idea of “an eye for an eye’, and condones the taking of a life in the name of justice and law, scholars continue to place greater emphasis on the Quran’s preference for preserving life. Traditionally, Islamic judges have enforced capital punishment in the belief that Sharia considers the practice a deterrent, though research consistently shows that executions have no impact on the reduction of crime. Under Sharia’s own tenets, officials implementing the rule of law are required to address this inconsistency.

To the outside world, it may look as if the Iranian government is immune to change, but beneath the surface it is impressionable. Sustained campaigning by international human rights organizations and activists has led to Iran amending its drugs laws, restricting the types of drug related offences that could receive the death penalty.

Ayatollah Sadegh Amoli Larijani, the head of Iran’s judiciary, ordered officials to review cases swiftly, and implement the new regulations, which limited the death penally to drug lords, armed dealers and those convicted of smuggling more than 50 kilograms of opium or 2 kilograms of heroin. This was a significant victory for children inside the country. The majority on death row involved in drug related crime are first time offenders who have committed low level offences, and for the most part are under the age of thirty.

Existing alongside the voices of dissent outside Iran, are the vocal opponents of child executions inside the country, who at times have been government officials themselves. In 2003, Ayatollah Shahroudi, who was then head of the Iranian judiciary, issued a circular letter to every judge, asking them to stop issuing death penalties for offenders under the age of 18. The circular worked. For a while, judges stopped handing out and implementing the death sentence for children, but they eventually set aside the letter and began to sanction child executions again, claiming that the contents of the circular were not legally valid. Whether the judges were coerced into changing their opinion is unclear, but the initial, enthusiastic uptake of the circular by these judges demonstrates an understanding of the conflicts child executions pose, both in terms of interpreting Sharia, and the current state of Iran’s unfair and outdated legal system.

Iranians are already divided on the issue of living in a country governed by deeply conservative Islamic principles. The idea that the Iranian government may be using capital punishment to instil fear internationally, not to prevent crime but to further its own foreign policies, also raises serious questions about whether the government is abusing, rather than honouring Sharia Law.

There can be no greater, more despicable act than killing a child and leaving their body hanging in a square, just to tell the world you’re capable of anything.