By Ahmad Rafat

Western governments have eagerly been awaiting the election of a new Iranian president – one who could be perceived as a reformist and moderate figure, and allow them to justify restarting nuclear negotiations and forging strategic partnerships with Tehran.

In recent weeks, Tehran received messages from the West (including during a secret meeting in Oman with advisors to U.S. President Joe Biden) that, even if it refused to contain its regional policies and its nuclear program, it should select a leader who could be portrayed as a moderate and reformist.

That leader is Masoud Pezeshkian, a 69-year-old heart surgeon, who became the ninth president of Iran after the second round of general elections on July 5. The elections followed the May 19 death of President Ebrahim Raisi in a helicopter accident.

According to official government reports, fewer than 40 percent of eligible voters went to the polls in the first round of elections, the lowest voter turnout in the Islamic Republic’s 45-year history.

“If it were not for the esteemed leader of the Revolution [Ali Khamanei], I do not imagine that my name would have come out of the ballot box so easily,” Pezeshkian said immediately after announcing his victory.

Before the opening of polling stations for the first round of elections on June 16, Khamenei had already selected Pezeshkian as the new Iranian president.

It is worth noting that Pezeshkian was disqualified by the Guardian Council three years ago, rendering him ineligible to run in the presidential elections. Yet following Raisi’s death, there was widespread speculation that Khamenei was seeking an alternative candidate who could ease tensions with European countries and the U.S.

Once again, the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic decided which candidate’s name should come out of the ballot box.

The portrayal of Pezeshkian as a ‘moderate’ is seriously misguided.

Pezeshkian has a background of leaning towards extremism since his youth: He served as health minister during former President Mohammad Khatami’s second term from 2001 to 2005, and has justified the actions of the Islamic Republic using softer language.

After the Islamic Revolution in February 1979, Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, ordered the closure of universities in April 1980. They were reopened following a massive purge of professors and students.

During an interview with Iranian State TV in 2014, Pezeshkian acknowledged his involvement in initiating the academic purge at the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. He admitted to enforcing a dress code at the university immediately after the 1979 revolution and before the official implementation of the compulsory hejab law, which forced female students to wear headscarves, long coats, and trousers when attending classes.

Pezeshkian, who was president of Tabriz University’s Faculty of Medical Sciences from 1994 to 2000, considered the policy of prohibiting male students from specializing in women’s health as one of his significant accomplishments. The practice is similar to those implemented by the Afghan Taliban, which have been met with severe criticism from the international community and Western governments.

During President Khatami’s second term, Pezeshkian held the position of health minister and faced multiple impeachment attempts by the Majlis (Iranian Parliament) because of issues such as medicine shortages, medical tariffs, and excessive foreign trips.

Using the term ‘moderate’ to describe Pezeshkian, despite his poor human rights record during his tenure from 2001 to 2005, is perplexing.

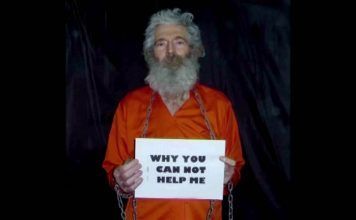

On June 23, 2003, Zahra Kazemi, an Iranian-Canadian photographer-journalist, was apprehended while preparing a report on the gatherings outside Tehran’s Evin Prison by the families of individuals detained during the mass demonstrations that occurred in the same month. Despite holding a permit from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, Kazemi was taken into custody, and died after spending 18 days in the hospital.

The prison authorities claimed that Kazemi had sustained injuries either from an accidental fall or by purposefully hitting her head against the bars of her prison cell, leading to her being hospitalized. Prosecutor Saeed Mortazavi, who had issued Kazemi’s arrest warrant, claimed that she died of a heart attack.

The then Health Minister Pezeshkian categorized Kazemi’s death as intentional, and dismissed the allegations made by Kazemi’s mother, who had mentioned signs of torture on her daughter’s body. Pezeshkian asserted that he examined Kazemi’s body and did not find any bruises or cuts on her face. That’s although, in a report issued that year, the Majlis’ Investigative Commission referred to the “injuries” found on the photographer’s body.

Iran’s Acting Foreign Minister Says Indirect Talks With US Ongoing

Pezeshkian denied Canada’s request to conduct its investigation into Kazemi’s death, stating that “Iran possessed sufficient expertise to examine the body and determine the cause of her death,” and adding that “the country prohibited foreign investigative teams from interfering.”

While many Western media outlets describe Pezeshkian as a reformist, he has repeatedly stated in his interviews since 2011 that he does not consider himself to be a reformist.

“I have said a hundred times, and I say again, that I am not a reformist,” Pezeshkian has said.

During a recent election campaign, he scolded a Tehran University student for criticizing Khamenei, emphasizing that he himself not only accepted Khamenei but was also “transformed by the leadership,” and adding that “no one has the right to insult and disrespect him [Khamenei].”

In recent years, Pezeshkian has referred to the widespread popular protests in December 2017 and October 2019 and the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ revolution in 2021 not as “protests” but as “disturbances.” However, he has condemned the violent tactics employed by security and police forces to suppress the demonstrators.

The anticipation among Western and Middle Eastern nations of a shift in the regional strategies of the Islamic Republic, or a reassessment of its nuclear program, after the new government takes over on July 30 is, again, a misconception.

In a July 2 interview with the Financial Times, former Foreign Minister Kamal Kharazi (in office from 1997 to 2005,) who currently leads the Strategic Council of Foreign Relations in Iran, stressed that Iran’s foreign policy was not dictated by governments but by Khamenei.

It is worth noting that Pezeshkian’s first act as the new president was to send a message to Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of the Lebanese Hezbollah. This action itself underscores the direction of the future government’s foreign policy.

In the message, Pezeshkian highlighted the Islamic Republic’s stance against Israel, affirming that “the resistance movement in the region will not tolerate Israel’s oppressive actions towards the Palestinians.”

Pezeshkian stated that the “Islamic Republic of Iran has consistently backed the resistance of the people in the region against the illegitimate Zionist regime,” and added: “This resistance is deeply ingrained in Iran’s core policies, the teachings of Imam Khomeini, and the directives of the Supreme Leader, and will persist with vigor.”