By Amir Taheri

In the 1960s, as Iran emerged from decades of instability triggered by the Allied invasion and occupation in World War II, the Azerbaijan crisis, the aftershocks of oil nationalization and a looming demographic explosion, the nation’s governing elite desperately looked for a shortcut to economic transformation.

With oil income steadily, though slowly, increasing, the government could mobilize greater resources for development. Iran did have a pool of skills in diplomacy, bureaucracy and classical military.

What was lacking, however, was a pool of managerial skill and experience to bring ambitious projects to fruition as quickly as possible.

In the early days, the pool in question consisted of a few dozen young men, many of them US-educated and having gained experience by working for Point IV, the aid program set up by resident Harry S. Truman to help World War II allies like Iran that were not covered by the much larger Marshall Plan, which was focused on Europe.

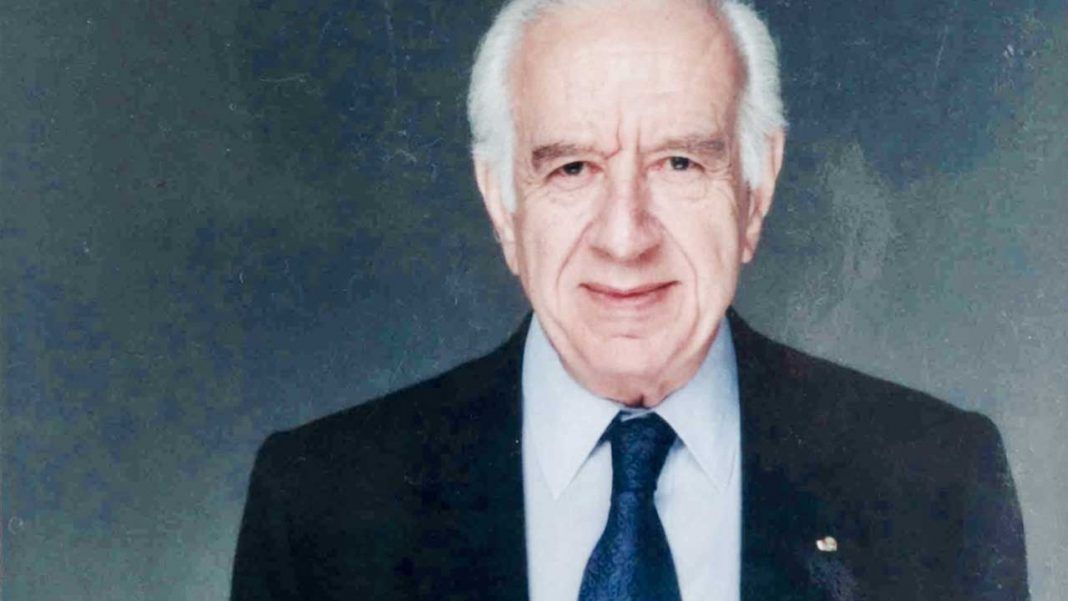

Abdolreza Ansari, who has sadly passed away in Paris, belonged to that generation of young, forward-looking and can-do Iranians who combined a deep attachment to their ancestral culture with modern skills of management.

It was, therefore, natural that Ansari should quickly establish his reputation as a rising star of the emerging technocratic elite gathered around Mohammad-Reza Shah and committed to realizing his ambitious dreams.

In those days, the technocrats who were to play a crucial role in Iran’s economic and social success over the following decades benefited from what amounted to an unofficial training scheme on the job.

A young technocrat could move from post to post in a short time, acquiring different skills before being recognized as the best player in a particular field.

Mr. Ansari moved from heading the Khuzestan water and power department to becoming Deputy Finance Minister, then Minister of Labor and Minister of the Interior.

I first met Mr. Ansari when he had been sent by the Shah to transform my home province into a launching pad for Iran’s economic modernization. But as if gods, or fate, were testing his mettle, his first task was to cope with one of the perennial floods that turn the low-lying valley at the foot of the Iranian plateau into a massive lake.

A deft handling of the crisis — which meant that the big flood claimed almost no lives and was quickly brought under control — revealed Mr. Ansari’s courage, selfless determination and composure under pressure.

Very soon, the slogan “Go South Young Man,” which first started as a tongue-in-cheek quip, became a reality, as large numbers of peoples moved in from other parts of Iran to work in the booming oil industry, the new agro-industrial complexes and the largest hydroelectric projects launched anywhere outside Europe and North America.

Khuzestan, a well-watered land in a largely dry country and a four-season climate, had great potential for agricultural and industrial development.

Initial seed money from the government attracted a growing flow of domestic and even foreign investment which, in turn, was used as a magnet for young talent from all over Iran.

Mr. Ansari, then a dashing young man with the looks of a matinee idol, presided over what came to be known as the “Khuzestan miracle.”

David Lilienthal, who had made his reputation with the Tennessee Valley Authority in the United States, visited Khuzestan in the early stages of the big Karun hydroelectric project and praised Mr. Ansari’s management of the province as “top notch.”

Washington Post editor Alfred Friendly, also a visitor to Khuzestan, described Mr. Ansari as a “model governor, mixing deep immersion with his own culture with knowledge of the most advanced management techniques.”

Success in the south put Ansari on a trajectory for greater responsibility at the national level.

As Minister of the Interior, one of the four regalian positions in the Cabinet, Ansari showed that he could be as good a politician as he had been a technocrat-cum-governor.

He pushed through a radical reform of old electoral laws which had always led to disputes while enabling big landlords, clerics and local notables to influence the results. He also presented a reconfiguration of provincial divisions to better reflect historic background and potentials for future development.

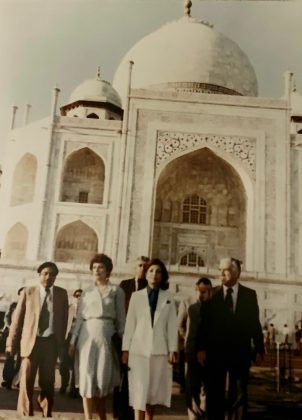

One of Mr. Ansari’s many “peculiarities,” as his detractors charged, was his insistence on “going there and seeing things.” Thus he became the first Iranian Interior Minister to visit all provinces, including the remote and often neglected Sistan-and-Baluchistan.

At the Interior Ministry, he discovered a long-standing scam that consisted of inviting real or even bogus Western consultants to offer recipes for development based on wishful thinking expressed through pseudo-scientific jargon.

His campaign for a more centralized approach to planning, with the help of the Planning Organization’s chief Safi Asfia, contributed to a thorough revision of Iranian thinking about developmental philosophy.

Not unexpectedly, friends and foes alike started to circulate Mr. Ansari’s name as a future prime minister. Alone in his generation of public servants, Mr. Ansari had acquired experience both on the ground, as project head and then provincial governor, and at ministerial headquarters in Tehran. His tenure as Minister of Interior had also brought him into direct contact with political groups, official parties, and lobbying interests of all sorts.

However, due to a combination of circumstances, among them his lack of a killer instinct, he was sidelined and did not reach the top of the greasy pole.

Was he bitter about that? I put the question to him decades later. “Yes and no,” he said. “Yes, because I feel that I did not do all I could for my beloved Iran. And, no because I had the chance to serve in a new and exciting field.”

The new and exciting field was the Royal Organization for Social Services (ROSS) with Princess Ashraf, the Shah’s twin sister, as patron.

The chief task of ROSS was to provide a safety net for the more vulnerable sections of Iranian society and fill the gaps in educational, welfare and health coverage offered by the government.

The organization played a crucial role in the mass literacy campaign that earned Iran UNESCO’s gold medal for success. It was in that context that Mr. Ansari pushed through the project to publish a newspaper for the newly literate. The paper, Rouz-e-Now (New Day), was printed and distributed by Kayhan and helped millions of newly literate Iranians to be informed and to join the national conversation.

After the seizure of power by the mullahs, Mr. Ansari was among the first Iranian former officials to build links with fellow exiles and start the “what to do next” conversation.

Early in 1981 we had a conversation about the possibility of starting a Persian-language newspaper in Paris but decided against it for political and logistical reasons.

We concluded that Iran was still experiencing the aftershocks of the political earthquake it had suffered and would be in no mood to consider alternative narratives in a sober mood. Logistically, in those pre-Internet days, regardless of how attractive our message was, it seemed impossible to build a wide audience inside Iran.

However, Ansari did not sit back and enjoy the delights of an imposed exile. He worked hard to help new arrivals from Iran who needed residence permits, jobs, housing and, above all a shoulder to cry on.

In effect, Mr. Ansari became a one-man Organization for Social Services for many Iranians forced to flee their homeland. One former ambassador who benefited from Mr. Ansari’s moral and material support said: “Abdolreza is doing on a miniature scale what he was doing on a big scale in Iran.”

In a sense, it is precisely this that makes Abdolreza Ansari and his generation of Iranian statesmen, politicians and technocrats important figures in a historic tragedy.

They could have done much more for their homeland, but were cut short by a treacherous fate.

Rest in Peace