TORONTO, Canada, April 27 (Reuters) – Iranian scientist Kaveh Madani’s career was in full bloom as he settled into his seat in early 2018 for a flight home from Bangkok to Tehran.

Though raised in the Iranian capital, the civil engineer had left the country at 22 to continue his studies abroad, earning renown for his research into how climate change affects water supplies. About six months earlier, however, the Iranian government had wooed the 36-year-old away from a prestigious professorship in London to a cabinet-level post as deputy environment minister.

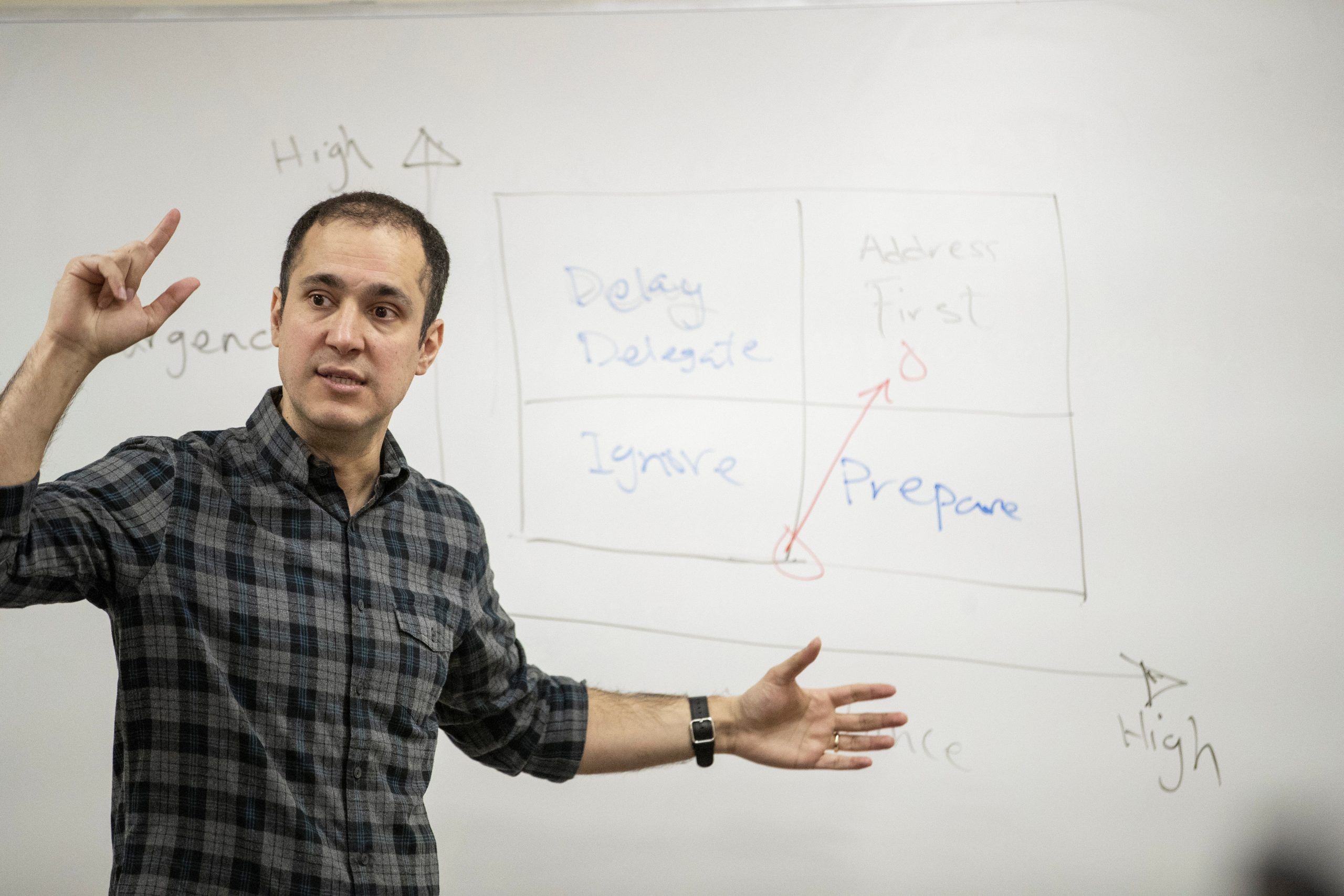

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2021-04-27T104558Z_316486972_RC2A4N9AH0W0_RTRMADP_3_CLIMATE-CHANGE-SCIENTISTS-MADANI-scaled.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Kaveh Madani, a Rice Senior Fellow at the MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies, interacts with students while teaching a class at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, U.S., January 28, 2020.REUTERS./FILE PHOTO” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

On this day, he was finishing up a four-country trip representing Tehran at meetings on water resources and other environmental issues. After takeoff, he connected to the Wi-Fi and checked his Twitter feed.

Several Twitter accounts had posted old pictures of him at a party dancing with women – considered a grave breach of decorum by ultra-conservatives in Iran‘s cleric-dominated government. The more he scrolled, the more alarmed he grew.

“Kaveh Madani, deputy head of the department of environment, gets drunk and dances in a building that belongs to the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Malaysia,” read one Tweet, written in Farsi. “He is laughing at the Iranian nation.”

Madani suspected that Islamist hard-liners were behind the post, and he worried that intelligence officers might be waiting to arrest him at the Tehran airport. It wasn’t idle speculation. A feud was playing out between ultraconservatives and the relatively moderate government of his boss, President Hassan Rouhani, and Madani had already been caught up in it.

Agents had arrested him when he landed in Tehran to take the job as a cabinet official the year before, and had subjected him to several days of interrogation on suspicion of being a Western spy – a common slur against internationalists. In the next few months, he was questioned and sometimes detained several more times.

This time, however, it felt different. This time, they had attacked him publicly. This time, he feared, he wouldn’t be freed.

“The way the Islamic Republic intelligence works, they don’t manage risk,” he said. “They remove risk.”

On that day, however, fortune favored Madani: He’d missed his direct flight to Tehran because of an unplanned meeting and was booked on a connection through Istanbul. When he landed in Turkey, he never boarded the plane to Tehran, and instead went into hiding.

Kaveh Madani’s career path, though tinged with perilous intrigue, speaks to the particular challenges faced by scientists and environmentalists in the developing world – both politically and practically.

Climate science has been politicized in rich nations, too, of course, including the United States and Australia. In Iran, climate change is political, but not in the same way. Iranian officials don’t reject climate change. Instead, they blame the country’s chronic water shortages and desertification on the Western industrial nations that have caused the lion’s share of carbon emissions. Yes, that’s a problem, Madani says, but he also believes it’s a fig leaf. He says his research has found that the government mismanaged water for decades, allowing it to be overused by developers and farmers and diverting it away from its source to cities.

There’s another difference between Iran and countries such as America and Australia: They don’t put scientists and policymakers in jail.

An even more fundamental problem for scientists in the developing world is a paucity of funding for all sorts of basic research. That’s clear from the rankings of the Hot List, a Reuters tally of the world’s 1,000 most influential climate scientists. Although the developing world accounts for about 70% of the world’s population, scientists working in those countries make up just one in 20 of the Hot List’s membership.

To win research opportunities, many bright young researchers go abroad to more affluent nations. That’s what Madani did, leaving for Sweden and then California for graduate school. Some never return.

“There’s very, very little opportunity to get funded,” said Saleemul Huq, a climate-adaptation researcher from Bangladesh whose son studied under Madani at Imperial College London. “So, we spend almost 100% of our time teaching and very little of our time doing research because the potential for getting funding to do that is very limited.”

Madani’s political troubles have had another impact. He took refuge in Toronto, disrupting his research. He was still occasionally publishing, but his output went down and he fell off the Hot List.

Reuters made numerous attempts to contact the Iranian government for this story. Reporters contacted officials at the Iranian mission to the United Nations in New York and attempted to reach officials in Tehran by telephone and email from Dubai. No one with the Iranian government responded.

Several of Madani’s friends and colleagues, in both the United States and in Iran, corroborated much of his version of events. Reuters also reviewed and translated tweets from the period immediately before he went into hiding, which confirmed he was a target of intimidation, as well as contemporaneous news reports of his detentions.

“WATER IS A BIG DEAL”

Madani, now 39, was born in Tehran soon after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, growing up with parents who lectured him on the importance of managing and preserving water. They both worked for a government agency that manages water resources in Iran, a nation that includes arid and dusty grasslands, snowy mountains, hot and humid coastal plains and lush, rainy forests.

He took their passion with him to university, making it his focus while other students were still trying to find their path.

“He was always explaining to people that … water is a big deal,” said Ali Mirchi, a fellow civil engineering student at the University of Tabriz who now teaches at Oklahoma State University. “And it’s already a big deal” in Iran. “It’s going to be a big deal around the world.”

After earning his undergraduate civil engineering degree in 2003, Madani left Iran to continue his studies in Sweden. From there, Madani went to America, where he earned a doctorate at the University of California, Davis. He later joined Imperial College London, teaching water management and game theory – a method of analyzing problems based on the available choices that each participant in the game has.

In several papers, Madani has taken those principles and applied them to water use problems. A simple example would be a farmer who needs water for irrigation and a developer who needs water for new homes. Both have water needs, and there’s enough for both if they take moderate steps to reduce their use. But if they distrust each other, they’ll grab more water than they need, depleting the supply for everyone.

Madani says these are the type of problems that governments are most qualified to equitably resolve by ensuring everyone keeps to the deal. And it’s this type of work where he feels he can make the biggest difference, bridging the gap between science, communities, government policy and climate change.

He said game theory is not a hammer for all nails. But it is a technique that helps him find solutions.

“It’s the mathematics of cooperation and conflict,” he said. “You can use it to either project the likely outcomes of conflict situations or decision-making situations, or to consult and advise and come up with strategies to get the result that you want.”

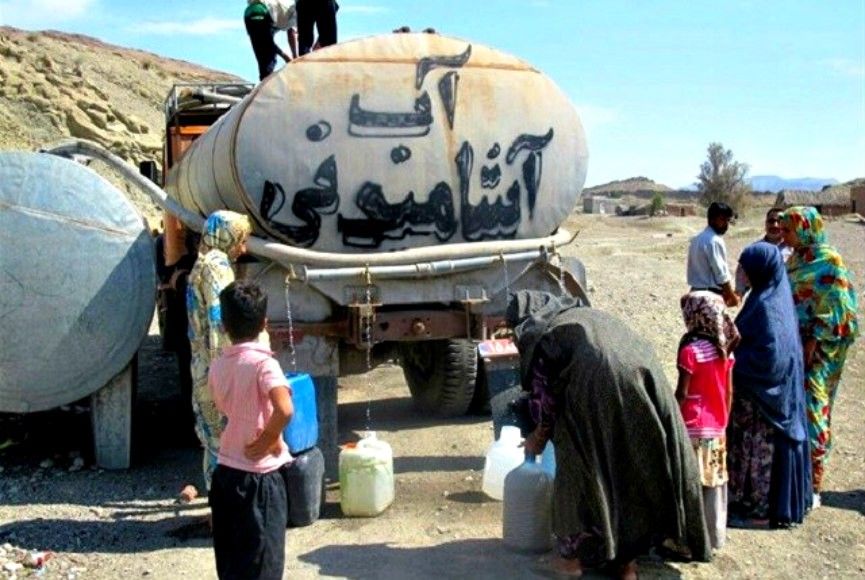

His primary area of study is managing freshwater, without which most life on land couldn’t exist. But as the planet warms with climate change, some parts of the Earth are seeing less rainfall, and water has become more precious. Iran is one of those places.

Water resources are a tricky subject in Iran given the government’s role in their management. But Madani has not been shy about publicly criticizing the government.

In 2016, before his return, he and his old roommate at the University of Tabriz, Mirchi, and another scientist wrote a paper – a follow-up to one Madani published in 2014 – that blamed the Department of the Environment and other agencies for what they described as “water bankruptcy.” Mismanagement had caused lakes, rivers and wetlands to dry up and resulted in desertification and more frequent dust storms, they said. Madani says the Iranian government hides those failures behind the excuse of climate change, which has indeed led to hotter summers and less rainfall.

“This makes the problem very tricky, especially for people like me who work in developing countries,” Madani said. “Because we have to warn about climate change and make sure climate change is recognized as a serious threat, but at the same time make sure that governments don’t misuse climate change.”

The 2016 paper was a direct challenge to the government. But some reform-minded officials at the Department of the Environment still wanted him to return to the fold, despite objections from hard-liners, he said. In September 2017, he left his burgeoning academic career behind and returned home to take the job as deputy vice president with responsibilities that included international affairs, social engagement and innovation.

CONTROVERSIAL RETURN

Madani was one of the most visible members of the Iranian diaspora to return to work with the government. It was a big deal. Here was a Western-educated, YouTube-posting, Twitter-cognoscenti member of the post-revolution generation coming home to help the country.

He was appointed as Iran‘s delegate to various climate negotiations and was given a diplomatic passport. In November 2017, he represented Iran at the COP23 climate-change implementation meetings in Bonn, Germany. The next month, he traveled to Paris for the anniversary of the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Many countries were represented by prime ministers and presidents at both gatherings. Madani represented Iran.

At home, Madani quickly made an impact, said a water specialist colleague in Iran. He used social media to recruit actors, politicians and even some clerics to environmental causes, most notably to discourage single-use plastic containers.

The water specialist said Madani also confronted officials over projects that moved water from one area of the country to another, which Madani says was damaging the environment where the water was drawn.

“In conferences, as a speaker, he was very outspoken,” said the specialist, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “He criticized people and officials. He tried to change their behavior.”

At the time, the colleague was hopeful that Madani’s return signaled that Iran was ready to deal with some of its chronic water problems. Madani and his associates, he said, had plans to create a center for monitoring water resources and forecasting droughts.

But trouble was brewing. “The system had not handled a case like me,” Madani said. “There were so many stories about reversing the brain drain and bringing the young generation back that they had a hard time getting rid of me or fully trusting me.”

When he first arrived in Iran, intelligence officers with the Revolutionary Guard detained and interrogated him for several hours about his time overseas and accused him of conspiring with other countries, including Israel, he said. The officers also confiscated his computer and phone, Madani said.

He suspects they hacked into his Gmail account and downloaded 14 years of emails – later using them on the day of his flight to Istanbul. Reuters was unable to determine who hacked Madani’s photographs and posted the denunciations on Twitter. Madani said he knows it was them because he couldn’t get into his email and had to ask his interrogators for his new password.

There was another arrest and several interrogations in the intervening months between his return to Iran in September 2017 and his decision to flee, but he was released each time. When he was last arrested, in February 2018, authorities also detained eight Iranian environmentalists working to protect the endangered Asiatic cheetah. One of the eight died in custody. Iranian officials said Kavous Seyed Emami, a Canadian-Iranian who was one of the founders of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation, had killed himself. His family doubts that. The rest of the group have since been sentenced to prison on charges of conspiring with a foriegn country or spying.

On his flight to Istanbul a little later that same year, Madani decided that his patrons had lost the internal battle. His colleagues in Iran were crushed. Their plans for a water-resources center were scrapped when Madani left. “The day he went from Iran, it was so dark a day for me,” the water specialist said.

Suzanne Maloney, an Iran scholar now at the Brookings Institution, was at the U.S. State Department when Madani worked for the Iranian government and followed his efforts and difficulties through news accounts and other sources. Like Madani, Emami and others, expatriate Iranians have returned to Iran to serve their country only to find themselves locked up, she said.

“I think Kaveh Madani was very lucky to get out of Iran without a worse outcome than he suffered,” she said. “And I’m sure it was a very harrowing experience.”

Bangladesh scientist Huq, who ranks 208th on the Hot List, said he and Madani had seen each other episodically through the years. Still, Huq didn’t know what happened to Madani in Iran until September 2019, 18 months after Madani went into hiding, when the two bumped into each other at a U.N. summit on climate change in New York.

Madani’s fate, he said, wasn’t surprising, given the limits on criticism of the government.

“If the space for critics is very limited, it’s almost impossible for us to function.”

CHALLENGES IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

Huq said a bigger problem for climate scientists in the developing world is the lack of funding for research.

For example, the 2014 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment report mentioned Bangladesh more than 100 times, citing scores of academic papers, Huq said. But only a quarter of the lead authors of those papers were working in his country.

Climate change causes acute problems for those living in the developing world, whether water shortages or failed crops. Individual governments must focus on practical and immediate solutions – by digging new, deeper wells, limiting irrigation or reusing sewerage to make potable water.

After all, Madani argues, most of those countries can do little to meaningfully reduce emissions anyway. With the exception of richer developing countries, including India, Saudi Arabia and even Iran, most developing nations are tiny emitters of greenhouse gases, so even if they eliminated all fossil fuels, it would do little to help deal with the consequences of climate change.

In Iran, Madani says that combating the effects of climate change and other environmental problems is complicated by Iran‘s volatile relationship with the United States and some of its neighbors, such as archrival Saudi Arabia.

Consider the international sanctions against Iran, put in place at various times by the United States, its allies and the United Nations to punish Iran for shipping attacks in the Persian Gulf, supporting international terrorism and its pursuit of nuclear weapons. In November, Madani published a paper examining how the sanctions are hitting the Iranian environment particularly hard.

For example, exporting refined petroleum products to Iran has been illegal for decades. So, Iran developed its own crude oil refineries. The result is dirty, polluting fuels that run dirty, polluting electrical power plants.

Likewise, exporting cars to Iran is also illegal. So, Iran developed its own car industry. The result is inefficient cars.

The sanctions also allow the Iranian government to blame the West reflexively for Iran‘s problems, said Maloney, the Iran scholar, when internal factors such as corruption or mismanagement are at play.

“I think that’s symptomatic of the Islamic Republic’s approach to all of its internal problems, to find some external party to blame for them,” she said.

RICH VS. POOR

Like Madani, Huq studied and taught overseas. Today, he heads up the International Centre for Climate Change and Development at the Independent University in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

He says there’s a distinct difference between climate change research in Europe and North America and the work being done in developing countries, such as Bangladesh.

Scientists in the West are good at working on technological solutions to climate change, such as solar technology or carbon-dioxide scrubbing systems.

He said scientists in poor countries such as Bangladesh rarely have enough money or expertise to do that kind of research. Besides, some of the worst effects of climate change, including longer droughts, dangerous heat waves, rising sea levels and more dangerous tropical cyclones, will almost certainly hit the developing world harder.

“The richer countries have the ability to develop and then bring hardware to countries like ours and install it with just a screwdriver,” he said, referring to devices such as modern windmills and solar panels. And that’s all well and good, he said, “but I would argue that the poor actually know a lot more about how to deal with problems of poverty and climatic impacts than the rich do.”

Bangladesh, for example, has adapted to the growing threat of tropical cyclones.

“In the past decades, we have had super cyclones which have killed hundreds of thousands. We had one in 1970 that killed half a million people.”

Last year, Super Cyclone Amphan developed over the Bay of Bengal and rapidly developed into one of the region’s largest recorded storms. But when it struck the Indian and Bangladeshi coast on May 20, only 128 people died, including 26 in Bangladesh.

“In the last decade, we have built the world’s best cyclone warning and shelter system,” he said. “Instead of hundreds of thousands of people dying, the number was in the dozens.

“The cyclone still happened. It still did a lot of damage. Houses, infrastructure, people lost their homes and their farms. But they didn’t die.”

It happened that way because scientists persuaded the nation’s leaders that the threat from cyclones was growing and then helped create a warning, evacuation and shelter plan, based on the best available research.

Lives were also saved by children knocking on doors.

“Kids went to different households and brought the widows and the mothers who don’t have anybody to help them,” Huq said. “The kids made sure that their own grandparents go to the shelter.”

Sometimes so-called solutions to climate change are less effective – and can even exacerbate the problem, Madani said.

When he was in Florida, Madani teamed up with one of his students, Saeed Hadian, a fellow Iranian, to examine the consequences of using alternative energy sources as demand for electricity increases and countries move away from fossil fuels.

Where there is plenty of unused land, acres of solar panels might make sense. In other places, where agriculture needs the land, nuclear power or offshore wind farms might be a better solution, Hadian argued.

California, for example, gets nearly a fifth of its power from hydroelectric dams. But those dams lose massive amounts of water from evaporation that could otherwise be used for farming and drinking. By comparison, less water is used or polluted when extracting natural gas and coal from the ground and used in power plants than is lost to evaporation.

Madani isn’t advocating the burning of coal, of course; his point is that some low- or zero-carbon choices – such as dams – can have unintended consequences for climate change, the environment and ecosystems. For some countries, the threat to water supplies posed by a hydroelectric dam might mean a natural-gas or nuclear power plant makes more sense.

Madani says it’s worse in North Africa and the Middle East, where governments have been building dams for decades as a cheap and clean source of electricity.

“Hydropower is not a good idea, but most politicians love it,” he said. “You sell it as renewable; you sell it as clean. And it comes with a lot of concrete. And it’s really good for the local economy, in the short run.”

In the long run, vast amounts of water are lost to evaporation. Demand for water around the dam almost always increases, and in regions seeing less rain because of climate change, it also starves downstream farmers, sometimes thousands of miles away in different countries, of water needed for irrigation.

“Beware of unintended consequences,” Madani said.

DROPPING OFF THE HOT LIST

In the months after he stepped off that plane in Istanbul, Madani was officially listed as a visiting professor at Imperial College London. In reality, he had gone into hiding.

Relying on old friends for help, he made his way from Turkey through Europe to North America. But even after Madani made it across the Atlantic, he didn’t feel safe. He spent about eight months bouncing between the United States, where he’s a permanent resident, and Toronto, where his wife had lived before they married. He did interviews and spoke at conferences, but no place was home.

In January 2020, he felt safer. He took a job as a visiting professor at Yale University’s MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies and split his time between the New Haven campus and Toronto.

Madani ranked 684th on the Reuters Hot List in mid-2019. By December 2020, however, he had dropped off the list. That’s because he was publishing less as he sought a haven. Even since joining Yale, he hasn’t published as much as he once did.

“There have been a lot of papers and invitations to join teams that I’ve said no to, because I was doing other things or I thought that what they’re saying is too theoretical and has no major policy implications or impact,” he said.

Madani plans to stay in academia but wants to do more in the lay world, where he can talk to the public, both in the West and Iran. He remains a prolific Farsi tweeter, sometimes criticizing, sometimes defending Iran. He’s also published opinion pieces, on subjects including smog in his hometown of Tehran, in publications such as the Guardian newspaper and online journals.

The Covid-19 pandemic has clipped his wings too. He was already worried about traveling because of threats from Iran, but his travel is now nonexistent, and he’s reduced to streaming video presentations. He keeps in touch with his aging parents back in Iran, now in their 70s, via WhatsApp. His father recently suffered serious health problems, and the separation is particularly hard to bear.

So his mother was excited when UCLA’s Center for Near East Studies streamed a conversation in Farsi with Madani in October on how Iran struggles with drought, water shortages and other environmental problems resulting from climate change, mismanagement, development and politics.

But during the presentation, which was carried on an Instagram live feed, his mother scrolled through the comments. The organized Madani haters were back, some of them attacking him by crudely insulting her.

“My mom was heartbroken,” Madani said.

(Reporting by Maurice Tamman; editing by Kari Howard)