By Maryam Zar

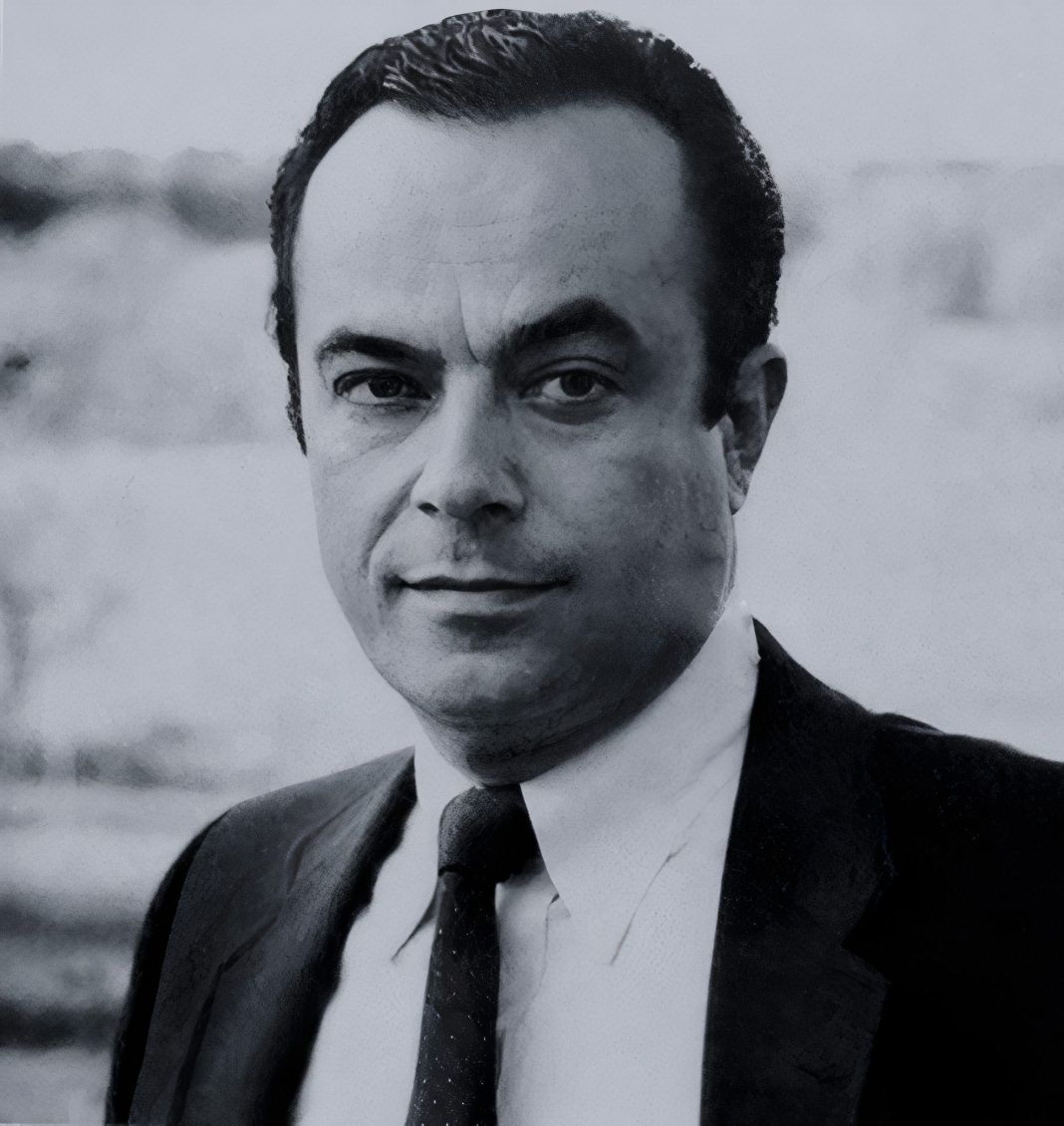

Dr. Habib Ladjevardi, who died in Washington D.C. on July 24, was a Harvard University scholar who made a lasting contribution to his country and community by establishing Harvard’s Iranian Oral History Project.

Born in Tehran on May 28, 1938, Ladjevardi was the youngest of five siblings. He came of age at a time when Iran was on a march towards modernity. His industrialist family was a major contributor to that endeavor.

While his father and elder brothers were leaders in the fields of commerce and industry, Habib was the young son who grew up with the luxury of idealism and the ability to view the world as a place of learning from which he could bring new ideas back to Iran. He was sent from a young age to the United States, where he attended middle and high school. He went on to study at the Universities of Yale, Harvard and Oxford. He got his Oxford doctorate as an adult working in Iran; his dissertation was about labor and trade unions.

While at Harvard Business School, young Habib had an idea that he would bring to what was then a fast-modernizing Iran. That idea would become the famous Iran Center for Management Studies.

By all accounts a charismatic man who was more interested in substance than in material wealth, Habib delved into history and sought patterns of progress that Iran could follow to achieve the future he believed its people deserved. He was less interested in the nuts and bolts of industrial development than in developing the human infrastructure that would help Iran grow and prosper.

Dr. Ladjevardi was also a believer in basic human fairness and in fundamental freedoms. He leaned more towards the political beliefs of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh and towards a democratic system than towards a system rooted in monarchy. While he and his family were close to Iran’s ruling family, Habib believed in empowering Iran’s labor force as a means of strengthening the whole of society.

With this in mind, Ladjevardi returned to Iran after completing his MBA at Harvard Business School and suggested to the Ministries of Industry and Education that they invest in a management school called the Iran Center for Management Studies. The school was to be fashioned after the methodology of Harvard Business School to train a new generation of Iranian managers who could compete with their European, American and Japanese counterparts.

This was a novel idea in 1960s Iran, and according to his friend and Harvard colleague, Dr. Roy Mottahedeh, the idea was met with a great deal of skepticism. Dr. Ladjevardi overcame that skepticism by investing his own money in the idea and by advocating for a new generation of leaders and managers who would understand marketing and advertising as well as sales and labor costs.

“My father realized early on that something important was happening in Iran, and the importance of preserving it,” noted his daughter, Leila Arsanjani, in one of several interviews conducted for this piece. “He subscribed to every newspaper that was published in Iran at the time, regardless of its political leanings.”

Dr. Ladjevardi also had the foresight to microfiche all of those newspapers and collect them for an eventual institute of higher education. He subsequently donated the original copies to the University of Maryland Persian Studies Center.

When Dr. Ladjevardi returned to Iran in the mid-1960s, he saw an Iran that was on the cutting edge, with industry growing at a fast pace, but management still centralized and one- dimensional. Within his own family business, for instance, his brothers and uncles were responsible for a singular function of the business. “Ahmad Ladjevardi was responsible for setting up the manufacturing plants and for production; Ghassem Ladjevardi was responsible for accounting, finance and banking; and Akbar Ladjevardian was responsible for sales, distribution, and marketing,” explained his nephew, Ali Ladjevardi.

[aesop_image img=”https://kayhanlife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/IMG-6213.jpg” panorama=”off” credit=”Dr. Habib Ladjevardi.” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionsrc=”custom” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Dr. Ladjevardi identified aspects of the administration and management of the family businesses that needed upgrading. He hired a British expert and brought him to Iran to help set up new organizational structures and internal administrative processes that were more decentralized and conducive to growth. He hired professional product managers to develop household products such as soap and detergent that would better serve Iran’s consumer base, and he developed training programs for company managers. He even enrolled several senior managers with high potential (who were not relatives) in the Executive Management programs at Harvard Business School. “These business approaches were novel and pioneering management approaches in Iran,” Ali Ladjevardi noted.

The Iran Center for Management Studies eventually gained the support of the Shah, who appointed his brother, Gholam Reza, to head the center’s board. Nearly 20 acres of land were gifted to the center, which was launched in 1970. The center was an inspiring project for Dr. Ladjevardi as well as for his longtime friend and fellow Harvard alumnus, the architect Nader Ardalan.

Dr. Ladjevardi put together a curriculum that would prepare Iranians who were talented in business and management to compete on the world stage. Ardalan took inspiration from the rich creative heritage of Iranian architecture and combined it with the modern building techniques that he had learned abroad to build the physical school. “The cultural relevance was important to both of us,” Ardalan explained.

Together, the two men launched this seminal project in their homeland. With the free hand that Ladjevardi gave him, Ardalan recalled that he was able to merge his studies in Persian architecture and design to produce “a modern project that could meet the functional and academic program demands,” allowing students and teachers to live, work and study on the premises.

The project began in 1970 on a “barren hilltop in Tehran, located somewhere between downtown and Shemiran,” Ardalan recalled. Once complete, the celebrated center opened to great fanfare, with prominent professors from Harvard and beyond joining Iranian royals and dignitaries, alongside professors and students chosen from among hundreds of young Iranian applicants. This was an important moment in Iranian history, and it was envisioned and carried out by Dr. Ladjevardi.

The celebrations took place in the Paradise Garden, which was inspired by the gardens of Kashan – where the Ladjevardi family hailed from – and the iconic Bagh-e-Fin. The final design of the Paradise Garden was a nod, not just to Iranian heritage, but to the source of the Ladjevardi family’s wealth: their rights to a waterway that fueled the thread-making and fabric-dying industry and that eventually led to a proliferation of factories and jobs underpinning Iran’s healthy textile sector.

The final design was sustainable and at one with nature. The ICMS hosted seven years of classes and graduates until several years after the Revolution. At that point, with the Shah and his government long gone, the Ladjevardi family escaped Iran, recognizing that the new regime would not treat them kindly, though they had been of great service to the nation.

Dr. Ladjevardi himself was “very upset a few months after the Revolution when his name appeared in the newspaper as one of the people who had removed their assets from Iran,” recalled his daughter Leila, who by then was living in Massachusetts. “He felt it was an affront to everything he believed in and had stood for. Even then, he spent a lot of time, energy and money on lawyers to try and clear his name.”

Meanwhile, the ICMS was transformed into the Imam Sadegh University by the Islamic Republic, and still functions as a prominent domestic university educating a student body of some 2,000.

Back in Boston in the 1980s, Dr. Ladjevardi was contacted by an old friend and fellow historian, Dr. Roy Parviz Mottahedeh, whom he had met at Oxford years earlier. Dr. Mottahedeh had recently been named the Director of the Center for Middle East Studies at Harvard, and he wanted Dr. Ladjevardi to join him as Associate Director.

It was there that Dr. Ladjevardi suggested the idea of the Iranian Oral History Project to Harvard University. This was a project that he had initiated a year earlier with the support of the National Endowment for the Arts. At the CMES at Harvard, he found an ally in Dr. Mottahedeh. By 1985, he had the support of an entire department.

Dr. Ladjevardi’s aim was to record the modern history of Iran for historians to look back upon and understand. “The Oral History Project was his way of making a contribution to the development of Iran’s post-revolution narrative, and memorializing it for the history books,” said his longtime friend, Iradj Bagherzadeh, founder and publisher of the prestigious IB Tauris publishing house.

Dr. Ladjevardi took scrupulous pre-interview notes (which his family later donated to Harvard), in which he jotted down ideas that would provoke thoughtful conversation with his interviewees. “He wanted to give them the freedom to talk instead of answering specific questions. He believed they would open up more this way,” his daughter Leila pointed out.

One of his early colleagues in Boston, Dr. Houchang Chehabi, now at Boston University, recalled that Dr. Ladjevardi chose to interview elite members of the political and business class of Iran in the late 1970s. His aim was to shed light on the decision-making that took place at the very top levels of government and business, leading all the way up to the years before the revolution. He interviewed more than 200 people for this historic project, so that “future historians could get a sense of how decisions were made in Iran, pre-revolution,” his daughter Leila explained.

One member of the Iranian elite with whom he spoke was Holakou Rambod, whose son remembered Dr. Ladjevardi as a kind and genuine man for whom his father had a great deal of respect. “He felt that Dr. Ladjevardi didn’t have another agenda beyond recording historical events before they were lost forever,” recalled Rambod’s son, Max. Even as a child witnessing these long interviews, Max got a sense that this was a knowledgeable man with a humble disposition who delved into many aspects of the events and personalities he chronicled, always checking and double checking facts and being scrupulous about the end result.

“He had a generosity of spirit and cared deeply for his family, friends and other human beings,” said Professor Shahla Haeri, who helped conduct some of the Oral History Project interviews and later helped form the Iranian Association of Boston (Khaneh-ye Iran) along with Dr. Ladjevardi.

In Boston and Cambridge, Dr. Ladjevardi recognized a need to bring people together, give them a center around which to celebrate a shared culture, and empower the nascent diaspora in and around Boston. Ladjevardi had come to the US as a young man and gone through high school there. He was comfortable in this new homeland and wanted to share the resources at his disposal to relieve the burden of others. One of his friends, ICMS colleague Eghbal Alavi, remembered the helping hand that Ladjevardi extended to her in the early days of her arrival in the US, when he used his network to help her secure meaningful work. She remembers how Dr. Ladjevardi brought together people with different backgrounds and viewpoints and treated them all with respect as he worked to create a hub for a newly forming community.

In those days, Iranians in Boston were looking for a way to coalesce and not lose their sense of community. To address this need, Dr. Ladjevardi founded the Iranian Association of Boston. “With the increasing number of Iranians in Boston, Dr. Ladjevardi felt the need to create a community to help preserve our culture through celebrations of major Persian events and talks on cultural topics of interest,” recalled IAB’s current president, Mehdi Zarghamee. “He wanted to prevent the loss of cultural identity among the younger generation and a sense of isolation among the older generation.”

He also wanted the IAB to be a democratic institution, where doors would be open to all Iranians seeking to preserve and stay connected to their cultural heritage. This was not to be a place of partisanship or politics, explains Zarghamee, but a place bringing together people who had lost their homeland and were now looking to adopt a new one. The center’s early objectives were quickly realized, and the center today holds celebrations of cultural importance, regular lectures on topics of interest to the community, and a program called “refah” which gives assistance to the needy. What is most significant to Zarghamee and some of the other early members is the democratic organizational structure, which has allowed the organization to thrive under successive leaders. The IAB is the embodiment of Dr. Ladjevardi’s democratic spirit and his mission to deliver it to the world around him. His problem-solving acumen and his selflessness are remembered in Boston, where his footprint remains strong both at IAB and at Harvard.

Dr. Ladjevardi is survived by two children, six grandchildren and a dozen nieces and nephews. “He was not at all like an elderly uncle,” recalled his nephew, Ali Ladjevardi. “He was a very sharing person.”

Above all, Dr. Ladjevardi was a father and a grandfather. He took every opportunity to attend soccer games to please his grandchildren, watch school plays and whip up his specialty burgers at family gatherings. “Most of his grandchildren were surprised about all that he had accomplished in his life, and the respect that he had garnered in the community, because he rarely talked or boasted about his accomplishments,” his daughter Leila noted.

Dr. Ladjevardi was, by all accounts, a humble man who never sought the limelight or longed for recognition. He sensed the need around him and asked himself what he could do to make a difference. He wished to make an intellectual contribution to the world around him, a useful contribution to the history of Iran, and to make a loving impact on his family. He accomplished all of these goals with the humility of a man of great character.

“Any other nation would celebrate the likes of him,” said his friend, the writer Amir Soltani, who knew Dr. Ladjevardi as a child. “I had the privilege of being in the company of a profoundly decent man.”

He was really amazing man very active , honest loved iran very much . I am sure he is in heaven now