Kayhan-London

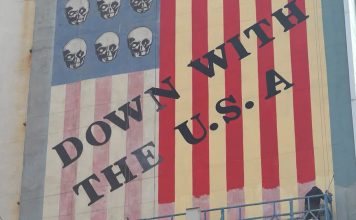

LONDON — Iran’s authorities, evidently oblivious to the country’s numerous other problems, have been pressing on with their unpopular hijab crackdown. The initiative is intended to enforce modesty and Islamic dress norms, which typically focus more on women’s attire in public, notably the headscarf.

In 2022, the vigor and violence of this crackdown sparked a nationwide revolt. Yet Tehran insists that is hardly a reason to stop its flagship policy. In any case, Iranian authorities are indifferent to public opinion — as confirmed by the largely boycotted elections they keep celebrating — and have now decided to extend the hijab crackdown, called Nour or Light, to young men.

To be fair, in principle, modesty rules apply to everyone. After the 1979 revolution that brought the Islamic Republic to power, the humble T-shirt became a risqué if not strictly illegal piece of clothing — even in summer. In recent decades, young men might also be stopped on the street for a piercing, long hair or “rap-style” hairdos, as interpreted by the police.

New targets

Now, police are honing in on shorts. The Tehran-based daily Hammihan reported on July 31 that several young men had been detained over the past two months, then fined, for wearing shorts or bermudas. The logic is that showing your legs is as provocative as girls showing their hair.

The state was “always more sensitive about women.”

Yet as Hammihan observed, these boys were then taken to police stations, where they were exposed to the gaze of policewomen. One detainee, Amir Ali, told the daily he and others were stopped a month ago in one of Tehran’s main boulevards and taken to a station “where we were treated well and told to phone our families to bring us a pair of trousers.” They were then released provisionally, and later paid a fine before a magistrate.

On the platform X, one user observed that the arrests of men were erratic and not as forceful as those of women. She wrote she had phoned the police days before to report a man exposing himself near a primary school, but that the police never came.

Modesty for everyone

The Nour crackdown, which began in the first half of April 2024, fits into the “Hijab and Modesty bill” that has yet to become law as it awaits final approval by the Guardian Council, a body of senior jurists. The draft law, approved by parliament, defines unsuitable attire for men as any outfit that “reveals their bodies or parts of the body below a person’s chest or above the ankle or the shoulders.” In addition, women must also cover their wrists, and should not wear tight clothing.

Women who violate these rules face large fines, and possible jail terms of “between five and 10 years” depending on the judge. The idea is that immodest clothing incites sensuality, threatening the family, which is seen as a pillar of social stability and public security.

Existing penalties are not harsh enough to deter violations.

Tehran-based sociologist Simin Kazemi told Hammihan that the crackdown on shorts a likely an attempt to show that the state is being fair and indiscriminate. She noted that wearing shorts had become an act of protest or solidarity with women among some men.

Yet sociologist Shirin Ahmadinia told the daily that clothing restrictions for men were not new and intensified in the 1980s, even if the state was “always more sensitive about women.”

The Nour plan is to be carried out “on an experimental basis” for three years. But deputy-head of the police in the city of Qazvin, Qasim Rezai, said on July 24 that the initiative was effectively permanent because Iran would never stop “promoting moral values.”

The problem, Rezai said, is that existing penalties are not harsh enough to deter violations, creating more work for the police and courts, and therefore undermining their authority.