By Laura van Straaten

Hours before opening weekend for her much-anticipated movie “The Bad Batch,” the

Iranian-American screenwriter and director Ana Lily Amirpour sat down for an interview with Kayhan Life to discuss her quick rise into the upper echelons of Hollywood and her life growing up, as she put it, “brown in America.”

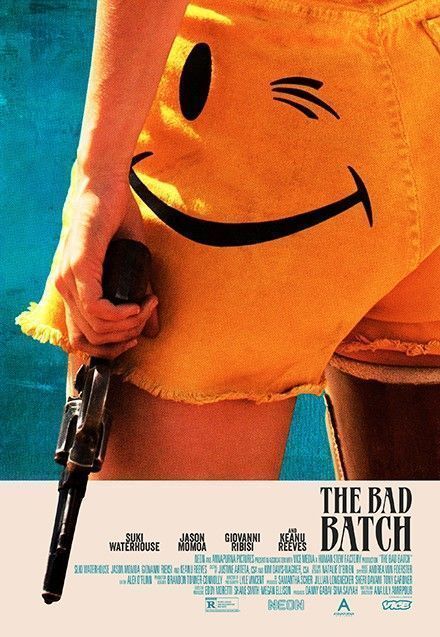

“The Bad Batch” is Amirpour’s second feature. It stars the up-and-coming actress Suki Waterhouse as a young woman who is ejected from America as “bad batch” and must fend for herself among other rejects in a lawless, violent, society (think: cannibalism). Amirpour’s impressive cast includes stars like Jim Carrey, Keanu Reeves, Giovanni Ribisi and “Game of Thrones” muscleman Jason Momoa. The movie opened June 23 in 30 theaters around the U.S. to generally thoughtful and warm critical reception. (It is also available in some locations on iTunes and Amazon.)

“The Bad Batch” is Amirpour’s second feature. It stars the up-and-coming actress Suki Waterhouse as a young woman who is ejected from America as “bad batch” and must fend for herself among other rejects in a lawless, violent, society (think: cannibalism). Amirpour’s impressive cast includes stars like Jim Carrey, Keanu Reeves, Giovanni Ribisi and “Game of Thrones” muscleman Jason Momoa. The movie opened June 23 in 30 theaters around the U.S. to generally thoughtful and warm critical reception. (It is also available in some locations on iTunes and Amazon.)

Amirpour, 36, first made a name for herself at the Sundance Film Festival in 2014 with her debut feature, a ‘vampire Western’ called “A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night,” which she boldly presented with all dialogue in Farsi and shot in black and white. (The idea for the film came to her when she realized that a woman in a chador could resemble a bat.)

Both features were favorites on film festival circuits and in 2016 Amirpour was invited to join the Academy of Motion Pictures, the second Iranian to do so; two-time Oscar-winning director Asghar Farhadi was the first. “This year, since I get all these screeners and I get to vote, so I was out of control passionately into it!,” Amirpour said of the Academy Awards, “It feels good to vote for all these movies you love.”

Amirpour, who goes by Lily, lives in Los Angeles and grew up in Bakersfield, a mid-sized metropolis in central California built around agriculture and oil production.

But despite a youth that included the quintessentially Californian “skater girl” phase, she’s kept her connection to Persian culture strong; when told that her Kayhan Life interview will likely be published in both Farsi and English for Iranians around the world, she excitedly chirps: “My peeps!”

The gamine filmmaker spoke in her high-floor suite at the Vale Hotel in Brooklyn, with clear views of the skyline and streets of New York far below.

Your first film featured vampires. Here, there’s cannibalism. Why?

My observation of the human animal is that we are very vicious to each other all the time for reasons much harder to understand than hunger. People are capable of tearing each other to pieces. That’s my point.

Do you feel you’ve faced any challenges as an Iranian director in Hollywood?

Look, making a film is an extremely difficult thing to do. It involves years of energy, passion, work and millions of dollars and the faith of many, many people . . . You know, I like to think of Amelia Earhart. She is someone who loved to fly planes. She was a girl. But I am pretty sure she didn’t spend a lot of each day tripping out on the fact that she was female. I think she just wanted to fly her plane. And so that’s what she did.

But if anything I can do can be useful, mazel!

Wait, “mazel” is Hebrew! And I saw in another interview that you used the Yiddish word “verklempt” to describe being overcome with emotion. Are you Jewish?

[She laughs.] I love the word “verklempt”! No, I’m not Jewish but I have a lot of Jewish friends, and you know, there are a lot of Jewish Iranians!

My father’s family is Muslim and my mother’s family is Bahá’í. . . . I imagine how life and reality would be different if my parents didn’t emigrate – twice, because they went to England [first] and then came to America. Talk about brave. It’s crazy. And the Bahá’í side of my family – with [Ayatollah] Khomeini after the revolution – they could not enroll in school if they were Baha’i, so were basically living behind closed doors. There were waves of violence.

Not unrelatedly, in “The Bad Batch,” you’ve created a dystopia where certain people are literally cast out by the government and left to fend for themselves . . .

When you say ‘dystopia,’ I always marvel at that word, because there’s no such thing as utopia. There’s just maybe this chance to create a bubble-corner-safe space within dystopia. And the problem with the world is that we are not paying attention to how much dystopia there is.

Because it’s too painful?

It’s too painful. You have to survive. You need comfort.

How far do you think this dystopic world you’ve depicting on the big screen is from the present moment?

It’s 100% the emotional reality of right now. If you just leave your hubs of comfort, sophistication and modernity, there are a lot of people who don’t fit neatly into society and also don’t have a lot of the privileges. I think it’s a matter of where people’s attention is focused.

If social critique is key, why don’t you reveal much about how this society came to corral and discard all the outcasts? And – even though there are hints, and one character is clearly an illegal immigrant – why don’t you reveal why each character is considered “bad batch” material?

In life, while we don’t always know everybody’s story, we do know that some people are falling into the corners. Take the large homeless population on Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles. I go there and talk to people. But do I need to know every detail? Is that how you get empathy for people? I hope that people do a little bit of work and think and question and wonder . . .

I will say that I’m cooking up a “Bad Batch” TV show that would psychedelically spiral in many directions and maybe will satisfy that curiosity to know more.

Is there anything you want to say about the heated exchange that took place at your Chicago screening, when someone in Q&A questioned the violent death of the black character whose child then becomes an important pawn for the film’s protagonist, who is white? You got some heat on social media afterwards.

I am a filmmaker who is very conscious culturally, socially, racially, morally on every level of my observations of people and humanity. It’s part of what I’m making films about.

I think there are two separate issues. One is two human beings in a room, having a miscommunication. And then there’s this whole other thing that happens on social media that I don’t quite understand, which is when you have many people coming to a conclusion when they haven’t seen the film.

Aren’t there three things, really? The third being what’s actually on screen?

Well, yeah. And I don’t get to control every reaction to it . . .

It was jarring; I grew up brown in America, assimilating, and English wasn’t the first language. I know what it is to be ‘the other,’ my own experience of ‘the other’ . . . [But then] you realize that when you make a challenging piece of cinema, you have to be ready.

You were born the year after the Revolution, in 1980. Have you been to Iran?

I went in 2003. My mom wanted me to.

What were the circumstances?

I was living in the woods in Colorado in a kind of hermit moment, not knowing what to do as a citizen on earth. And it was my mom’s genius Jedi move to give me a little bit of global perspective, like on how much she did for me to have the opportunities I had, so I would maybe come out of the woods and join the human race! [She laughs]

I had aunts and family in Tehran. They are wonderful people, my family, and it was so cool to get to meet them and hang out. And I went up north too.

But the government and the way it is there, it just feels like someone is grabbing you by the neck all day long – that’s how I felt as an American. It was surreal.

Did it change you?

I really did come off that experience understanding that when I was living in the woods, it was such a cliché. I had been anti-American a bit, against the system, like, ‘I don’t buy into this.’ And then I went to Iran and just had this perspective of ‘Wow, we really have it good here!’ [Amirpour gestures to the view of New York outside the window.] No matter how chaotic and crazy it is, there is so much opportunity to be had, and you can really manifest a lot of things to come to fruition, if you work hard and fight.

But then, given that, getting back to the themes of your new film, you still look out this window here at America now and see it as a dystopia?

[She smiles.] I feel like it can only help if someone like me forces you to look in the dark corners. Where people don’t like to look.

(This interview has been edited and condensed.) All images courtesy of NEON.

#analilyamirpour #thebadbatch #agirlwalkshomealoneatnight#iranianamerican #hollywooddirector #iranianfilmmaker #keanureeves#jimcarrey #giovanniribisi #vampires #musclebeach #cannibalism#kayhanlife #kayhanlife #iraniancinema #sukiwaterhouse